It’s odd to think that to the under 40s, Magenta Devine is not a household name, immediately conjuring up in the mind’s eye a pair of shades and a designer outfit. To uncharitable types, that description might signify that she was an insubstantial figure, part of a generation of TV presenters whose contribution to the medium was frivolous and fashion-fixated and who therefore deserved to be be blown away, like superfluous tinfoil wrapping, into permanent obscurity. Sadly, Devine did suffer from depression having departed the limelight and was declared bankrupt in 2003. That, however, was a deeply unfair fate.

Devine was a pioneering figure in a new approach to cultural and current affairs programme-making that brought the graphic language of style magazines like The Face, Blitz, ID and GQ to the small screen. “Yoof TV” was derided and much maligned in its day, but it represented a thoughtful and concerted attempt to speak to young people in a less staid, more dynamic manner, and, despite its famous bouts of mindless frivolity, had more than a kernel of seriousness about it, particularly when Devine was holding the microphone.

Magenta Devine was born Kim Taylor; the name for which she became better known was supposedly invented for her by friend and music journalist Pete Frame back in the late 70s. She would work in Tony Brainsby’s PR firm, which represented among others Queen, Whitesnake and Thin Lizzy, but more key in her formation was her involvement in the New Romantic scene. A black and white image in 1981 taken by photographer Derek Ridgers reveals her as quite the subterranean specimen, with her box handbag and cane, long dress and heels, hair cascading in a Gothic riot over her as yet un-sunglassed eyes.

Oh, wow; this photo of Magenta Devine by Derek Ridgers, 1981 pic.twitter.com/mqvfITUTgY

— Dave Haslam (@Mr_Dave_Haslam) March 6, 2019

The New Romantic movement was dismissed as the preserve of cocktail-supping narcissists, flaunting their inauthenticity to a tinny synthpop soundtrack. It was, in reality, the radical offshoot of the punk movement, a genuine revolt into style, whose frankly courageous practitioners refused to be kept down in the early Thatcher years. You didn’t merely have to be, you could become; dressing defiantly up, rather than down. Flaunting your invented self rather than knowing your place became almost a political imperative in those recession-hit years.

Having dated and then broken up with Tony James of Sigue Sigue Sputnik, the much-hyped but short lived New Romantic group, Devine’s TV career began with Network 7, a show conceived by Janet Street-Porter and Jane Hewland, whose maxim was “news is entertainment and entertainment is news”. Along with colleagues Jaswinder Bancil and Tracey MacLeod, she was one of a raft of presenters whose personalities were deliberately tailored, Spice Girls-like, with her billed by her own admission as the “bitchy one”.

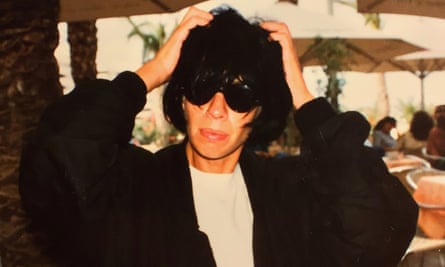

It was a billing she successfully failed to live up to. She was noted for wearing shades constantly; Dame Edna Everage, when interviewed by Devine, gently upbraided her for her choice of eyewear, recommending her own transparent spectacles. Devine herself plausibly explained that “I only wore sunglasses because I hated messing about with eye makeup, I’m useless at it.” She was only persuaded to wear transparent lenses during items on graver topics in her shows.

Certainly, the moral effect her shades had on her was impressive. Unlike later yoof TV presenters such as Amanda De Cadenet she was never exposed as poorly briefed, gormless or self-absorbed. I was interviewed by her myself while working for Melody Maker (for an item about George Michael) and was impressed by her methodical calmness and discreet, unflappable intelligence. This could have been Joan Bakewell. Whether reporting from the frontline of an acid house event, or presenting an informative item on Dublin in her Rough Guide series or calmly putting a typically blustery, snarky John Lydon in his place, she was the appropriate frontperson for a style of TV which, initially at least, sprang from a good countercultural place, genuinely wishing to inform rather than patronise young people.

Later, of course, Yoof TV mutated into the dismal The Word, a braying freakshow for the Friday night back-from-the-pub crowd. But Devine had largely disappeared from our screens by then. She was very much of the 80s, stylish, attractive but never an object of the sort of boorish, sexist attention of the laddish 90s. She was forgotten; now that she has gone, however, she should be remembered as a representative of a lost era of TV idealism, when style and substance went hand in glove.