A Small Rocket Maker

Is Running A Different Kind of Space Race

Astra, Darpa's rocket startup of choice, is preparing to launch satellites into orbit in record time

The 40-foot-long, 4-foot-wide rocket loomed over the quiet suburb of Alameda, Calif., on the morning of Jan. 18, near the Pottery Barn Outlet. A handful of engineers and metal wrenchers got to work early, setting up the rocket and connecting it to a mess of electronics and tubes. The device stood up straight, with the help of some black metal scaffolding. Its bottom third gleamed aluminum; the rest, actor-teeth white. Over the course of the day, the team pumped in various gases and liquids to prepare the rocket’s valves, chambers, and other components for a crucial test.

Shortly after midnight, the rocket was ready for an exercise called a cold flow, meant to ensure that its propellant tanks can handle liquid fuel. Once the team had filled the rocket, taken the needed measurements, and checked for leaks, they simply evacuated the machine by releasing huge volumes of liquid nitrogen into the air. The thing about liquid nitrogen is that it must be kept supercold to remain liquid. It boiled instantly on contact with the outside air, creating a billowing white cloud that stretched out more than 200 yards. With the team’s floodlights beaming down on the test site, this odd fog monster easily could have been seen by anyone living in the houses as close as 2,000 feet away. Soon, though, the rocket was trucked off toward its next temporary home, a spaceport in Kodiak, Alaska.

Until speaking with Bloomberg Businessweek, Astra, the three-year-old rocket startup behind the test, had operated in secret, rolling nitrogen clouds aside. The company’s founders say they want to be the FedEx Corp. of space. They’re aiming to create small, cheap rockets that can be mass-produced to facilitate daily spaceflights, delivering satellites into low-Earth orbit for as little as $1 million per launch. If Astra’s planned Kodiak flight succeeds on Feb. 21, it will have put a rocket into orbit at a record-setting pace. Chief Executive Officer Chris Kemp says he’s focused less on this particular launch than on the logistics of creating many more rockets. “We have taken a much broader look at how we scale the business,” he says.

Going fast in the aerospace business is a rarity and doesn’t usually work out so well. But the U.S. government has made speedy rocket launches something of a national priority, and Astra stands as a Department of Defense darling right now. The Pentagon’s R&D arm, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or Darpa, made Astra one of three finalists in a contest called the Launch Challenge. The terms: Whichever startup could send two rockets from different locations with different payloads within a few weeks of each other would win $12 million.

Astra is the only finalist still in the running. Virgin Orbit, part of billionaire Richard Branson’s spaceflight empire that’s been working on its rocket for about a decade, has withdrawn from the contest. Vector Launch Inc., the third finalist, filed for bankruptcy in December. That’s left Astra in a competition against itself and physics, which may be why Kemp, a relentless ball of confident energy who dresses in head-to-toe black, is uncharacteristically trying to set modest expectations for the Kodiak launch.

“It would be unprecedented if this was a successful orbital flight,” he says. “We want to emphasize that this is one of many launches we will do in an ongoing campaign.”

The 42-year-old CEO spent almost five years at NASA, but he’s not a rocket scientist by training. He joined NASA in 2007 after running a string of internet startups, eventually becoming the space agency’s chief technology officer. While at NASA he shepherded an open source software project called Open Stack, which turned into a data center and cloud computing phenomenon. He left in 2011, hoping to capitalize on Open Stack’s success, but his next company, Nebula, found itself outgunned by Amazon.com Inc.’s cloud computing services; Oracle Corp. acquired Nebula’s piece parts in 2015. Unsure what to do next, he spent a couple of years hunting for fresh ideas, which is when he ran into Adam London, Astra’s co-founder and CTO.

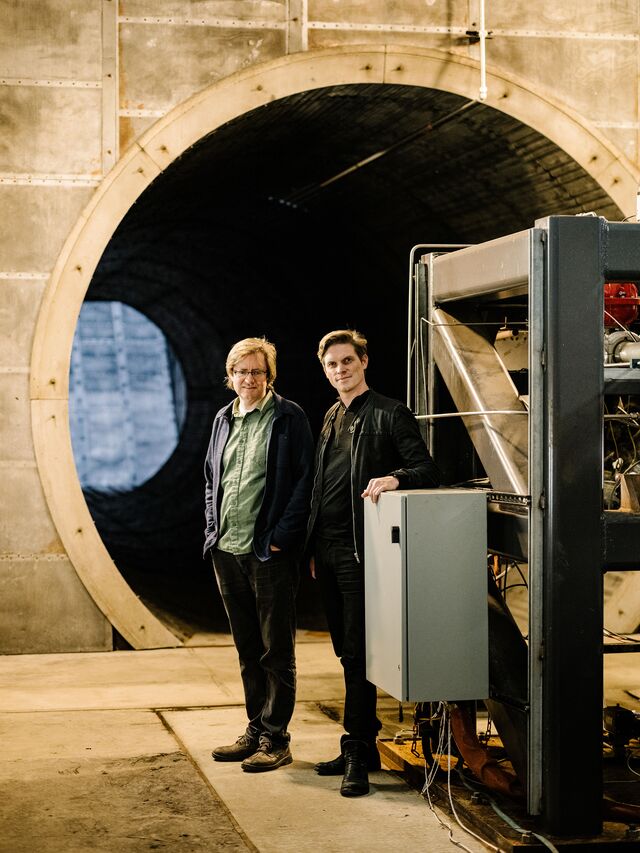

London is the rocket man, a 46-year-old with a doctorate in aerospace engineering from MIT and a talent for calculating drag coefficients and gravity losses in his head. He spent 12 years running a small rocket company called Ventions in the heart of San Francisco. Ventions’s handful of employees focused on miniaturizing rocket technology in their makeshift lab, living on NASA and Darpa contracts and the odd consulting gig. By 2016, London had grown determined to build the rocket of his dreams, but he needed a lot more capital. Kemp and his talent for winning over investors seemed like a good match, so after many chats, they joined forces. “I liked Chris’s enthusiasm, his ability to think about the story, and certainly his network,” says London, the measured counterpoint to Kemp’s bravado.

The rest of Astra’s 150-person team includes some legit aerospace veterans—former SpaceX employees such as Chris Thompson (part of the SpaceX founding team), Matt Lehman (propulsion), Roger Carlson (the Dragon capsule), and Bryson Gentile (the Falcon 9 rocket). But there’s also a large contingent of people who came either from gritty, bootstrapped rocket outfits or from other fields entirely. Much of the engine building has been done by Ben Farrant, a former Navy engine man who’s spent the bulk of his career in the auto racing world tuning vehicles. Les Martin, a launch and test infrastructure engineer, built test stands for SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, and Firefly Aerospace after learning electronics in the Marines. “I didn’t know the first thing about rockets, whenever I got into it,” he says. “But with these startups, you’re involved pretty quickly in just about every single aspect.”

Rocket Commerce

Data: SpaceX, Rocket Lab, Astra

Astra has raised more than $100 million from investors including Acme, Advance, Airbus Ventures, Canaan Partners, Innovation Endeavors, and Salesforce co-founder Marc Benioff. Billions have flowed into commercial spaceflight ventures over the past few years, often to newcomers that, like Astra, have shied away from competing directly with Elon Musk’s SpaceX and government-backed makers of large rockets.

The jumbo end of the market centers on rockets that fly roughly once a month and cost $60 million to $300 million per launch, typically carrying tons of cargo. Astra says its daily launches, meant to carry about 450 pounds of cargo to orbit, will be pitched to the dozens of companies making a new breed of small satellites, such as Planet Labs, Spire Global, and Swarm Technologies.

Whereas conventional orbital networks are composed of a relative handful of satellites the size of a car, Planet and its rivals produce tens to hundreds of basketball-size satellites for use in very specific orbits to photograph, track, and connect things on Earth in near-real time. At the moment no one really knows how big or viable the market for smaller rockets to ferry these satellites might be. Rocket Lab, a company founded by Peter Beck in Auckland in 2006, is the only small-rocket maker that’s actively launching. Rocket Lab enjoyed a banner 2019, putting six rockets into space, and has about a dozen more launches scheduled for this year. Its success has placed immense pressure on companies such as Astra and Virgin Orbit to catch up.

Astra has operated in secrecy partly to avoid being pushed to set unrealistic deadlines. Most of its workers have online résumés that list their employer as “Stealth Space Company,” and there hasn’t been a website. At the former Alameda Naval Air Station, Astra took over a decrepit building used decades ago to test jet engines indoors, which has helped keep its secrecy intact. The facility has two long tunnels that send fire and scorching hot air up through exhaust towers and thick concrete walls capable of absorbing the explosive impacts of tests gone wrong.

This setup has allowed Astra to conduct thousands of runs on its rocket engines without its neighbors noticing much of anything. It’s also meant Astra can put the engines through their paces on-site and make adjustments to the hardware quickly, instead of going to the Mojave Desert or an open field in Texas where other rocket makers typically run engine trials.

Kemp says that Rocket Lab’s going launch rate of about $7.5 million a pop is too high and that the company’s Electron rocket has been overengineered. Instead of using carbon fiber for the rocket body and fancy 3D-printed parts as Rocket Lab does, Astra has stuck with aluminum and simplified engines built with common tools. London’s team has tried to make the Astra radios, igniters, and even the rocket transport vehicle low-cost, high-performing, and easy to re-create.

Alongside its rocket test building, Astra has been assembling a 250,000-square-foot manufacturing facility that Kemp says will be able to churn out hundreds of rockets a year. “Our strategy is to always focus on the bottom line,” he says. “Nothing is sacred. We’re able to profitably deliver payloads at $2.5 million per launch, and our intent is to continue to lower that price and increase the performance of our system.”

The proof is in the orbital launch. Most spaceflight companies’ first crafts go boom in a bad way, but Rocket Lab has an almost flawless launch record. Beck, a self-taught rocket engineer, says his perfectionism is a selling point. “If someone wants to build a rocket that is super inaccurate, let them,” he says. “I’m not built to build shit.” Astra’s previous two launches, each of a smaller version of its current rocket, tumbled back onto the Kodiak coastline in 2018, breaking apart in spectacular pyrotechnic displays.

To win the $12 million, Astra will need to place a satellite of Darpa’s choosing into the right orbit. The Pentagon agency will then select another launch site—probably somewhere in California, Florida, or Virginia—and give Astra a few weeks to get a fresh rocket to the new launchpad. It would be an incredibly quick turnaround for an industry in which six to 12 months is a typical time span needed to calibrate the specifics around new launch sites and payloads.

“That is what was expected,” Kemp says. “Many of our objectives on those launches were achieved, and I guarantee we couldn’t have built our orbital rocket in three years if the team hadn’t benefited from that experience.” London is more circumspect—but comparably optimistic. “I did expect or at least hoped we would be in orbit by now,” he says. “But outside of things being a little harder than you would like, the broad direction and slope of things line up pretty well with our original plan.”

Astra has several rocket bodies awaiting the challenge on its Alameda factory floor. Kemp says the company has signed contracts for more than a dozen launches with paying customers, and it plans to create a launchpad in the Marshall Islands to match the one in Alaska. So far, he says, there are no plans to launch directly from the Alameda Pottery Barn.