Algohorror, the Creepy Visual Mash-Up Art Created With Algorithms

Eyes, teeth, and Botticelli feature prominently.

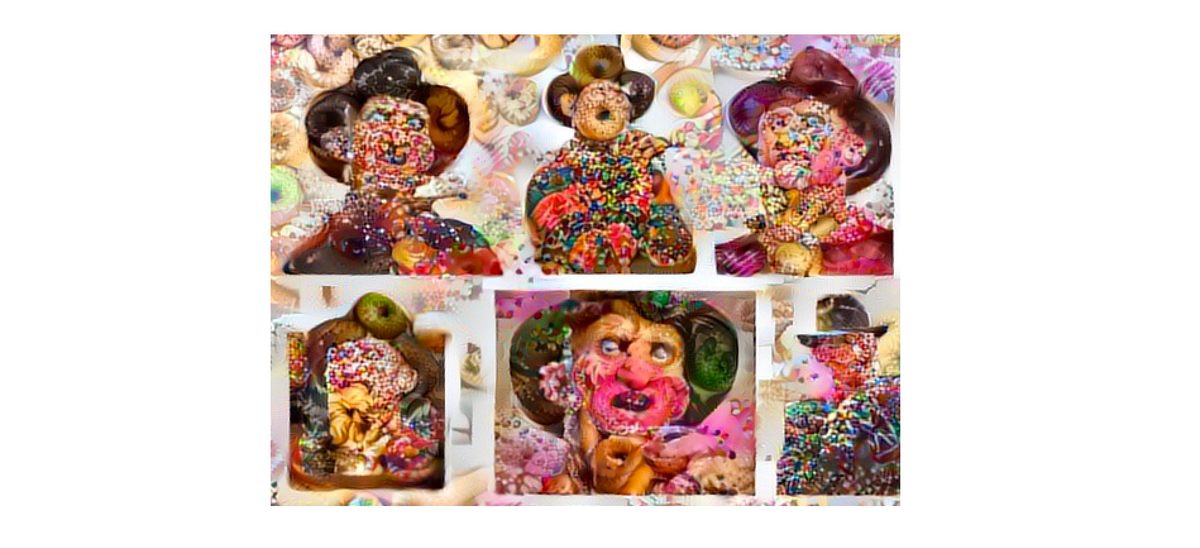

How would Botticelli’s Birth of Venus appear if it were painted as a cerebral cortex? Would you eat a Big Mac covered in an old man’s face? What if Freddy Krueger was composed not of mottled flesh, but Dunkin’ Donuts?

These are the questions that, one can only imagine, kept digital artist Chris Rodley up at night. Then he found a way to answer them, using an image-generating neural network developed by Artificial Intelligence researchers at the University of Tübingen. Conceptually, it’s pretty simple—you upload any image, and then apply the style of another image (think brushstrokes, lines, colors) to the initial one. It’s not just an picture mash-up; according to Rodley, it’s better to think of it as “texture synthesis.” The style-transfer network, known as DeepArt, which was originally developed to emulate painting styles, was already widely known in the tech world. But whereas in the past it had been used to transform pictures of Mom into Michelangelos, Rodley began testing its limits with an eye toward the macabre.

The results? Unrealized counterfactuals turned into unsettling realities. Rodley had effectively created his own genre, which he calls Algohorror—art that is not only horrific, but horrific in a way that is “distinctly algorithmish.”

When he says something is algorithmish, Rodley means that the image looks like it was created by a computer. There are certain characteristics that these images share—strange warpings, blendings, and incoherences—that a person wouldn’t think to include in an art piece. This is not to say that DeepArt is somehow more creative; oftentimes, the generated images are just blurry and incomprehensible. It simply means that algorithms pick out different visual patterns than we do, and the results can get freaky.

It’s a bit like giving Salvador Dalí Photoshop along with a generation’s worth of pop-culture references and telling him to go crazy.

Throughout his creative process developing Algohorror, Rodley has learned quite a bit about what people find horrifying, and how algorithms can be used to enhance the horror in our lives.

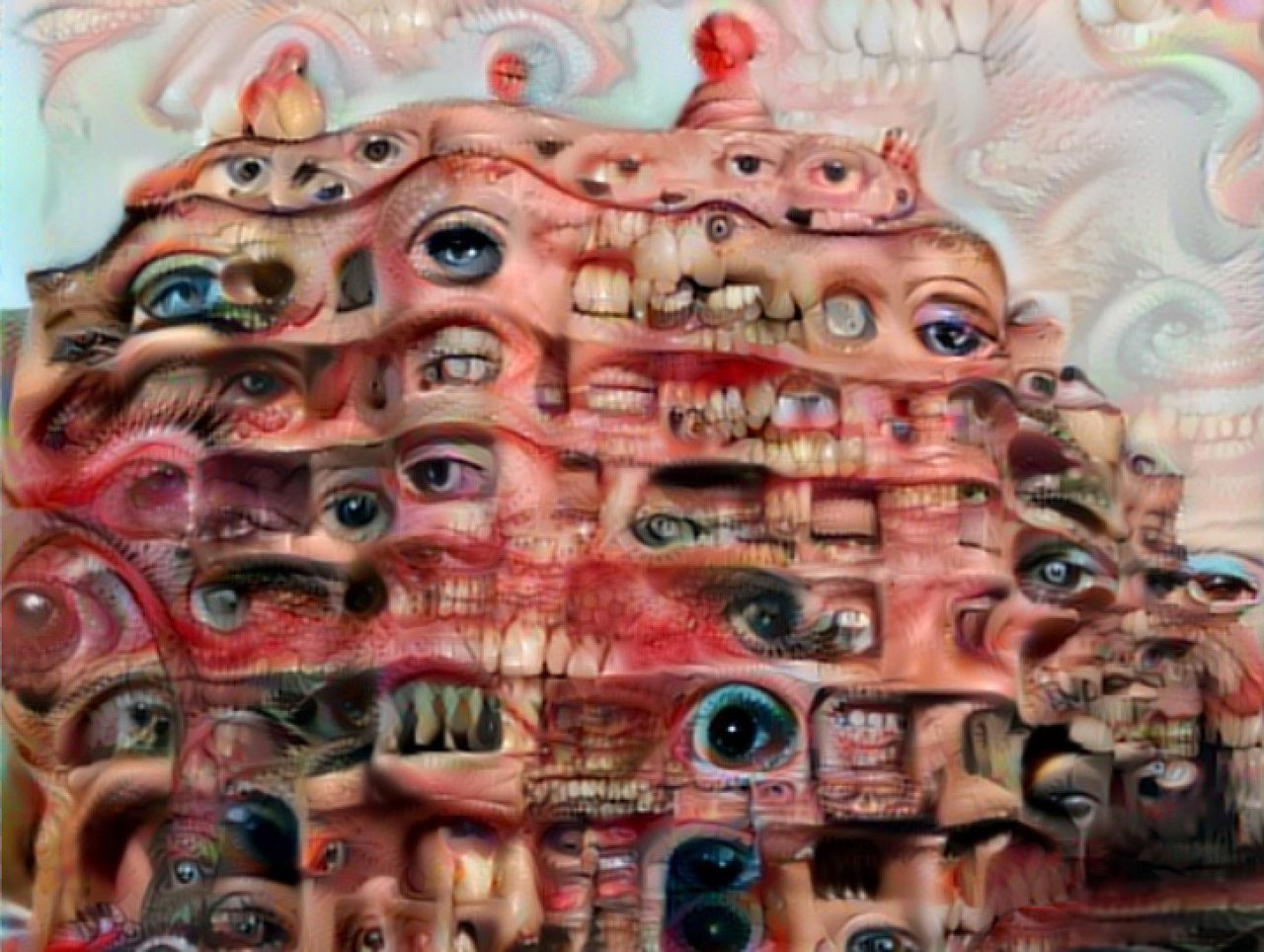

Anatomy, for example, is a widely shared source of dread. “Eyes and teeth,” Rodley says, “are sort of a hundred times more scary than other objects.” While it’s a bit odd that such familiar face parts can disgust, there’s no question that Antoni Gaudí’s Casa Eyes & Teeth wouldn’t make the best summer home. Whatever the biological cause of this visceral reaction, it’s likely the same mechanism that activates trypophobia (warning: click at your own risk), a feeling that is both stomach-churning and perversely interesting.

Likewise, Botticelli’s Cerebral Cortex of a Patient with Epilepsy During Surgery is another eerie display of blood and guts mapped onto beauty. Of course, neither of these images is particularly groundbreaking. Horror connoisseurs are well-aware of the main tropes that comprise the genre: bio-mechanical creatures, monsters, clowns and dolls, body horror.

Some Algohorror images are just an extension of the latter, preying upon our natural distaste for gore. But what Rodley is really trying to do with Algohorror is venture outside of these narrow archetypes. To that end, he’s aimed less for gruesome and more for unsettling.

This means blending images that aren’t traditionally horrifying—some of his best creations are cocktails of banality. We expect eyes to unnerve people; but stock photos (Rodley actually finds them “creepy because they’re so perfect”) and golden retrievers? Not so much. And yet, there’s something about Stock Photo Model Botticelli and Golden Retriever Botticelli that makes one a bit queasy. In violating our expectations, these images create the sort of subtle horror that comes from feeling that something isn’t quite right.

Rodley has also had success preying upon people’s pareidolia, the natural human inclination to see familiar patterns in chaotic places. Strawberry Skulls is a great example of this phenomenon; at a cursory glance, it just looks like some fruit. But if your eyes linger, you can make out the skulls hidden in the seeds, like picking constellations out of the stars.

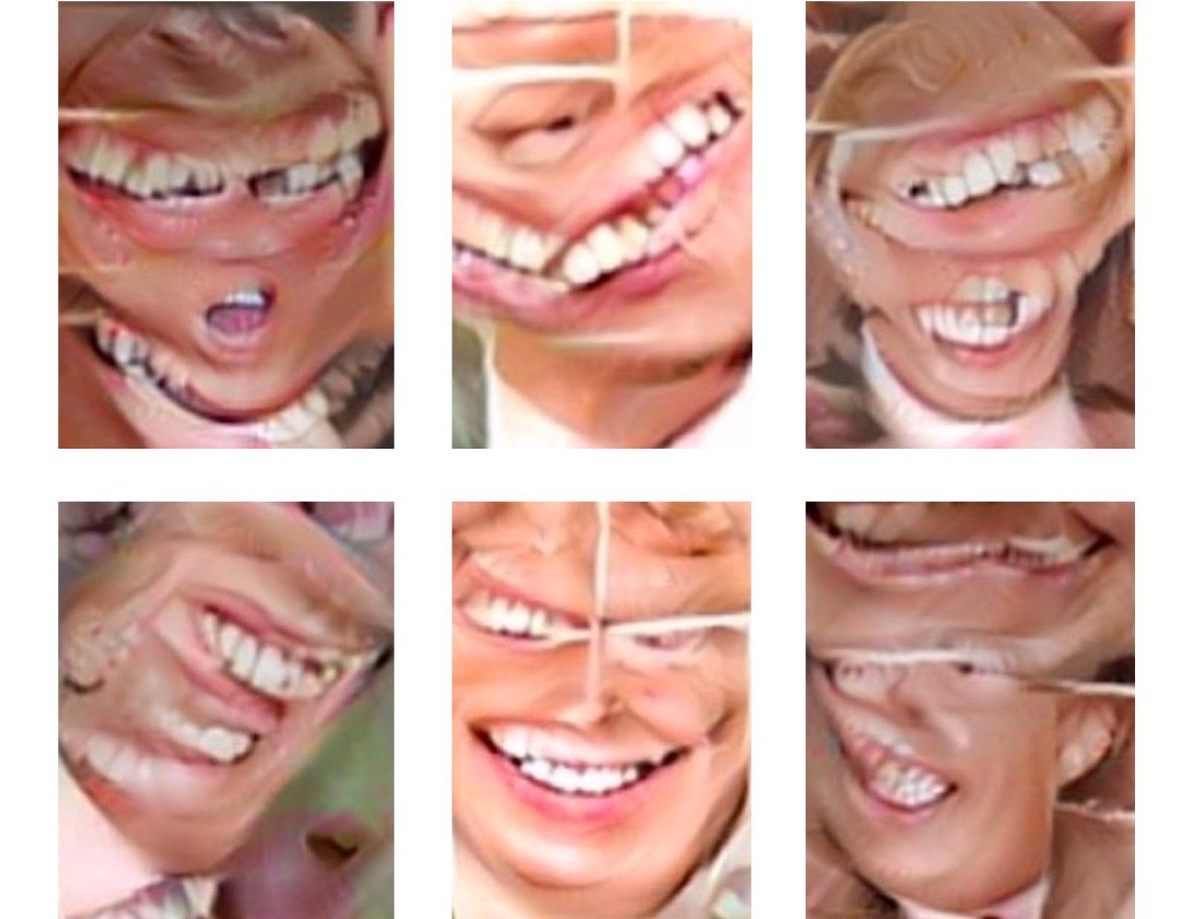

Another tactic Rodley uses to wring horror from modest images is visual metaphor. Toothpaste Advertisement Trump, for example, derives most of its unsettling nature from the content rather than the composition.

Rodley thinks the horror in this particular picture comes from the facade of gleaming incisors. In real life, he says, “It’s the ones with the perfect teeth that are often the bad guys.” In other words—you’re a lot less likely to be carved up by Freddy Krueger than bamboozled by a billionaire who had braces.

For all the Halloween enthusiasts out there, Algohorror should be seen as reason for unbridled optimism. You can find horror in anything, as long as you have an algorithm to help you out.

Want to create your own works of Algohorror? Visit DeepArt.io—and share the extra-freaky ones with us by sending them to ella@atlasobscura.com.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook