Eager beavers: How nature’s engineers can help save the planet

23 May 2019

Environmental journalist Ben Goldfarb’s epiphany arrived at a conference of evangelical Beaver Believers in 2015. The resulting book, Eager, which he brings to the Hay Festival, argues elegantly and persuasively that beavers can help save our troubled planet.

Ben Goldfarb had recently graduated from Yale University when he started to radically change his attitude to landscape. The reason?

My mental model of what aquatic ecosystems should look like omitted beavers... I needed to revise my conception of a healthy stream to include these incredible rodents.Ben Goldfarb

"Most of us can’t comprehend what North America looked like before fur traders arrived, trapping millions of beavers from the continent’s rivers and lakes."

In Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, Goldfarb makes the case that the near eradication of these once ubiquitous rodents had a profound impact on the North American continent’s landscapes and ecosystems - and by extension the environments of Europe and Asia. And that these “ecosystem engineers” can help humans fight drought, improve water quality and even address climate change.

He also writes about becoming part of a growing coalition - AKA the Beaver Believers, subject of an eponymously named feature-length documentary - that works to restore their populations and make the scientific case for doing so.

But what's so special about beavers anyway?

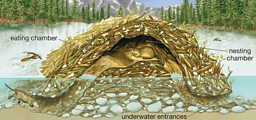

The classic beaver behaviour is that they build dams to create ponds and wetlands that provide shelter and food. They inadvertently create huge amounts of habitat for other creatures as well. Goldfarb notes that in the American West, wetlands cover 2% of the land area but support 80% of the biodiversity.

Frogs and salamanders breed in beaver ponds; juvenile trout and salmon use ponds as rearing habitat. Waterfowl forage in beaver ponds and even nest on beaver lodges. Woodpeckers will use dead trees killed by rising water levels. An incredible array of species has evolved to take advantage of beaver engineering.

What have beavers ever done for us?

Water storage

This is particularly important in arid areas such as California. In Nevada's Susie Creek, land management and beaver reintroduction combined to form a perennial stream; previously in July and August it had been still. The entire valley was irrigated, creating 100 acres of plant and tree growth. The local farmers now use the 1000 pounds of grass generated per acre to feed their cattle, so that there is a pro-beaver cluster among Nevada’s ranchers.

Pollution capture

Wetland creation mitigates against the major environmental problem of algae bloom by storing nitrogen and phosphorus. A Rhode Island study found that returning beavers capture between 5% and 45% of nitrates from southern New England’s watersheds.

Saving species

Beaver ponds expand surface water and improve quality by filtering and trapping sediments and recycling nutrients. Shaded, deep pools provide refuge for fish and support a wide diversity of wildlife. A 2016 study in the Pacific Northwest found a 52% survival increase in juvenile steelhead trout, a threatened species. The habitat is also perfect nesting and foraging territory for perching or passerine birds, and is also loved by bats.

Combatting climate change

Wildfires create terrible air pollution in the western United States. A network of beaver ponds can stop fires and provide a refuge for animals. The organic matter at the bottom of beaver ponds effectively stores carbon.

The fall and rise of the beaver

Unfortunately for beavers, pelts of their dense fur were highly prized. As early as the 1500s, intense trapping took place throughout Europe and Asia. The Eurasian beaver was virtually exterminated and North America and its native beaver became the new source of pelts for international commerce.

Colonists came to internalize this much drier, beaver-less landscape as natural... every generation accepts a bit more environmental degradation.Ben Goldfarb

The first European fur traders arrived in North America and went about ransacking the continent’s beavers. Europeans trapped beavers out of every single river, stream, lake, and pond they found, or traded for pelts with Native people.

In 1609, while searching for the Northwest Passage, English explorer Henry Hudson sailed up the river that would later bear his name into the Manhattan region and found French traders bartering for furs with Native Americans. The area became a thriving trading post, and beaver and other skins travelled through New York Harbor and on to Europe for the manufacture of hats and coats.

The search for beaver-trapping opportunities was a big driver for the later westward exploration of North America by European countries.

When Lewis and Clark conducted their famous expedition in 1804-6 they observed beaver habitat as far as the eye could see in the Missouri Basin. The naturalist and bird artist John James Aubudon explored the same territory 38 years later and could not find a single beaver.

Geronimo and 75 other beavers were literally dropped into the back country of Idaho in 1948, using parachutes left over from WWII.

The North American beaver population was somewhere between 100 and 400 million before the arrival of Europeans. At its lowpoint in the late-1800s it was down to 100,000. As beavers vanished, the wetlands they created dried up. Streams eroded and millions of acres of watery habitat was lost. Colonists would not have any conception of how the landscape had changed.

In the early 1900s, naturalists and biologists started to realise how important beavers are, and began relocations and reintroductions all over the United States. Goldfarb says, “They’re really resilient animals. They’re rodents, so they reproduce pretty readily. They disperse widely. And they’re good at making their own habitat. They were also assisted by humans.”

In New York, the state introduced about 20 beavers from Canada and Yellowstone in 1904. Just 11 years later, there were 15,000 beavers in the region descended from those early relocations. Those New York beavers would disperse into other states and recolonise the landscape.

In 1948, beavers were literally parachuted in to the wilds of Idaho. Parachutes left over from the war and crates - metal of course - were used to successfully land 75 beavers after an animal called Geronimo led the way as a test pilot.

What makes beavers special?

- Goggle-type eyelids called a nictitating membrane

- Time underwater: 15 minutes

- Fur-lined lips

- Dense, double-layer fur

- Duck-like feet

- Multi-use tail

- Self-sharpening teeth coloured orange by iron in the enamel

Culture clash: Humans and beavers

The successful return of beavers meant, of course, that they started to bump up against people. When they'd last been prevalent, the horse and cart was the primary mode of human transportation. Now railways, power lines, highways and suburban sprawl had taken hold of the river valleys and lowlands that were once prime beaver habitat.

We’re consistently hostile to this animal that’s nearly as bold and ingenious as we are.

Goldfarb says, “we tend to feel hostile towards animals that cohabitate well with us. Beavers, in some ways, are a lot like us. Just as we modify our own surroundings to maximise our food and shelter, beavers are relentlessly driven to change their environment as well.”

“We like to build towns and farms and roads in floodplains, while they like spreading water all over those floodplains. The inevitable result is conflict, and, in most cases, the offending beavers get killed.”

Battles raged in the 1980s and 1990s in states like Massachusetts, as environmentalists and vested interests fought to impose their visions. The state even implemented a control programme in which trappers paid for licenses and sold the pelts. An eventual repeal saw one local newspaper headline declare “Trap Law Leaves State Knee-Deep in Wildlife”.

One local newspaper headline declared “Trap Law Leaves State Knee-Deep in Wildlife”.

In Washington State about 1,500 beavers are killed annually and a smaller number are relocated. Goldfarb says, “I didn’t really become a “beaver believer” until a few years back... I was living in Seattle, where I was able to spend some time with a Forest Service biologist named Kent Woodruff.”

“He was director of the Methow Beaver Project, in central Washington, which live-traps “nuisance beavers” - animals that are blocking up culverts, flooding yards, or cutting down trees. The project relocates those beavers to headwater streams high in the Okanagan-Wenatchee National Forest. The idea is that up there the beavers can create fantastic wildlife habitat and store water without damaging private property.”

More sophisticated non-lethal solutions for beaver control have been developed in recent years. Flow devices and Beaver Deceivers regulate the height of a pond to a level acceptable to both people and beavers. Beavers are particularly drawn to damming culverts under roads, and these solutions reduce subsequent flooding by 90%.

The most loyal customers for these devices are transportation agencies. A study in Virginia found the state's Transportation Department was directly saving over $400,000 from its annual road repairs and maintenance bill.

Once friction points like roads are protected, Beaver Believers think that the 'cultural capacity' for beavers becomes whatever the landscape will allow - with all the attendant benefits that brings.

Some innovative landowners and flow device evangelists have become heroes in the Believer movement: Skip Lisle from Vermont began aged 15 and since setting up a full-time business has beaver-proofed entire counties, declaring “we can beaver-proof the entire freakin' world”.

“Let the beaver do the work”

Goldfarb says, “One of the mantras of those who work in beaver restoration is ‘Let the rodent do the work’. This animal can provide us a huge amount of help - storing water, improving water quality, creating wildlife habitat, even sequestering carbon.”

“Beaver restoration suggests a new approach to ecological restoration in general. One that is more holistic and in tune with the natural world.”

Beavers in Britain

In Eager, Goldfarb devotes a full chapter, Across the Pond, to the beaver story in Europe and the UK. By 1900 the remaining Eurasian Beaver population of little more than 1,000 was scattered to the wild edges of Europe, China and Mongolia. In post-Ice Age Britain, having lived alongside humans since 9,500 BC, beavers had completely disappeared by the nineteenth century.

In Europe, the kingpin of beaver reintroduction in the 1990s was Gerhard Schwab. Having studied wildlife at Colorado State University, he began in his native Germany and brought beavers to Croatia and then to Romania, Belgium, Spain and Bosnia. He has relocated over 1,000 beavers.

Goldfarb met Schwab when he was visiting the Bamff Estate, which lies in the catchment of the Tay River in Scotland where in 2005 he had helped the owners release beavers from Poland and Bavaria into a large enclosure. Soon after, Tay fishermen started to encounter beavers - the first wild ones to roam Scotland in four centuries.

More than 450 beavers, descended from illegal releases or escapees depending on who you ask, now live in the Tay's catchment. In 2009, Scottish Natural Heritage launched its own reintroduction scheme at Knapdale Forest in western Argyll.

Debate has raged in Scotland around rewilding, with our own Believers sometimes ranged against farming and fishing industry lobbies amid stories touting wolf and lynx reintroductions. But scientific studies in this country have produced evidence of the positive environmental effects of these now established beaver populations.

In May 2019, the Scottish Government granted beavers protected status, making it illegal to kill animals or destroy established dams and lodges without a licence.

Ben Goldfarb talks to Andy Fryers at the Hay Festival on Saturday 1 June at 19:00. Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter is published by Chelsea Green.