Scientists believe they are on the way to finding a cure for haemophilia A, the bleeding disorder that currently requires sufferers to inject themselves every other day to avoid life-threatening complications.

One dose of a gene therapy given experimentally to 13 patients by NHS doctors in the UK has allowed them all to come off treatment. These were men – most sufferers are – who would not only bleed without stopping from an injury but would bleed into their joints even in their sleep causing pain and disability, without frequent injections of a clotting factor. None of them now bleeds spontaneously in that way.

“I think it’s a huge step forward,” said Professor John Pasi, Haemophilia Centre director at Barts Health NHS Trust and one of the authors of the study. “Gene therapy for haemophilia has historically been the Holy Grail. Our patients have to treat themselves at least three times a week and even then they may still bleed. The treatment burden is massive.

“The opportunity to give them a one-off treatment perhaps for a lifetime but maybe for many years is a huge opportunity. It could transform their care.”

Patients were recruited from around England and all injected with a copy of the single gene responsible for causing blood to clot, which they were missing at birth. The treatment given at a low dose in the first two patients did not work. But the 13 subsequently treated at a higher dose have all stopped their regular injections. More than a year on, 11 of them have levels of the blood clotting protein Factor VIII that are at or near normal.

The results of the trial in nine of the patients are published in the New England Journal of Medicine, together with an editorial by Dr H Marijke van den Berg, vice president of the World Federation of Haemophilia. She hails the trial and a second study into gene therapy for people with a resistant form of the rarer haemophilia B as “leading the way to a cure for haemophilia”.

If the therapies can be perfected, she writes, “children born with this devastating disease could benefit from a life without bleeding.” The treatment would be particularly welcomed in the developing world, where patients cannot get access to clotting products, she points out.

Globally, various types of haemophilia affect around 400,000 people. In the UK, around 2,000 people have severe haemophilia A. The best known sufferer historically was the young Russian Tsarevich Alexei, who had haemophilia B and whose treatment by the monk Rasputin has often been linked to the fall of the Imperial family.

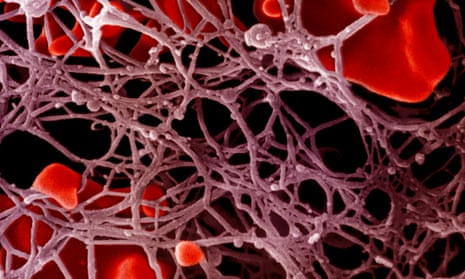

Scientists always thought it ought to be possible to find a gene therapy for haemophilia, but it has taken many years of unsuccessful attempts. One of the chief problems was finding a suitable virus to act as a delivery agent, or vector. The researchers have used an adeno-associated virus, which does not cause disease but could rule out the therapy for people whose immune system has encountered it in the past.

The 13 patients will be closely followed to discover whether the therapy lasts and a bigger trial will need to be done before the treatment can be licensed. There will then be the issue of cost. “This is going to be hugely expensive therapy,” said Pasi. “The average cost in the UK of current treatment is £100,000 per year per patient for a lifetime. You can see what numbers can clock up. It is the elephant in the room.”

Jake Omer, 29, who lives in Billericay with his wife and two small children, has been living with haemophilia all his life. For the last 18 months, since joining the trial, he has no longer had to give himself intravenous infusions. His levels of the blood clotting protein Factor VIII are higher than the average man in the street, he says.

“It means I don’t have haemophilia any more. It’s crazy,” he said.

Omer was two when he was diagnosed. “I was pottering about as a child and fell over in the kitchen and cut my lip. The bleeding didn’t stop. After one or two days of waking up in a pool of blood, I was taken to the hospital,” he said. Life for his parents in Romford then became one of anxiety and frequent trips to the Royal London Hospital.

“They’d have to drive me to the Royal London and then hold me down to get the injection in,” he said. “I was back and forth every two or three weeks.” It got better when his mum was able to give him the infusions once he was six or seven and better still when he could do it himself, at the age of 11. “But you always have to be a little bit more careful than your mates when climbing trees or jumping over things on the bikes.”

As an adult, he had to take holidays only in countries with excellent haemophilia centres, just in case. The bleeding that occurs into the joints caused arthritis in his ankles.

“The gene therapy has changed my life,” he said. “I now have hope for my future. It is incredible to now hope that I can play with my kids, kick a ball around and climb trees well into my kids’ teenage years and beyond. The arthritis in my ankles meant I used to worry how far I would be able to walk once I turned 40. At 23 I struggled to run 100m to catch a bus; now at 29 I’m walking two miles every day which I just couldn’t have done before having the gene therapy treatment.”