You never regret going for a run. That’s one thing runners can always agree on.

Some mornings, I pull on my running shoes the minute my eyes open and head out the door before I’m fully awake. It might be hard to get started, but I never come home and think, “I wish I hadn’t done that.”

On February 23, 2020, Ahmaud Arbery—a young, black man and former high school football player, went out for a run. But he never came home. He was shot in the street by two white men, a father and his son, who thought he fit the description of a man who committed a recent crime. They armed themselves and followed him, then shot and killed him. On May 5, video of the incident surfaced, which led to an arrest of the two men a few days later.

Running represents the freedom of movement. In America, we assume that as citizens, we have the right to move freely. But the common identity of being a runner and what it means to us—freedom and power—are shattered when Ahmaud Arbery is shot while out on a run. We see that the joy of running, the confidence we have, and the spiritual practice of putting one foot in front of the other, is not equally available to all Americans. For the African American community specifically, our movements have been constricted and controlled through violence and biased policing throughout history.

African-American runners don’t get to take freedom of movement for granted. Anyone whose skin and whose body has been made to seem threatening to the mainstream white American way of life, doesn’t get to take freedom of movement for granted. The freedom of being able to run where you want had to be fought for through a public and violent civil rights struggle.

The very act of running is a sign of privilege. At the very least, it signals that you have time for recreation and disposable income for gear or race fees. For some it is not only privilege, but also a radical act of reclamation because we live in a country where racism and segregation long determined access to freedom.

That is why running matters.

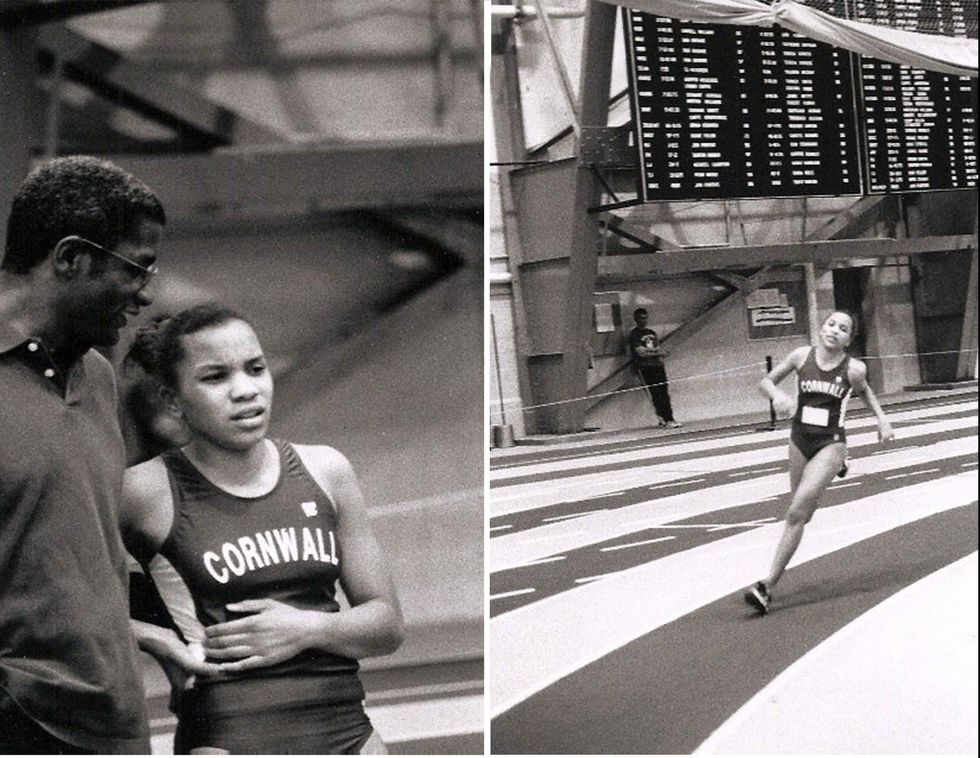

As the child of two track athletes, my earliest memories of the sport include running around a gravel loop with my family. Starting at age 11, my life was largely organized in increments of 400 meters. I ran track from seventh grade through college. My sister and I proudly followed in the footsteps of our uncles and our dad on the track—my dad, Paul Briggs, and his brothers Ed and Bruce, ran sprint events up to the 400-meter distance, and their brother Will still holds the school record in the discus at Newburgh Free Academy—and we also set records at our various institutions. After college, I wasn’t sure what else to do to fill the void. Throughout graduate school, I’d still find myself at the track, running intervals.

In 2011, I was living in Brooklyn, working in restaurants, trying to decide on the next step. I read the book,Born to Run, and after a lifetime of running on the track (and suffering from injuries), I set out on a road run. Once the girl who never wanted to run a single mile for warm-up, I transformed into a woman who needed three miles to warm up and six to hit the runner’s high. I ran on my own, early-morning loops in Prospect Park, and after I raced home, clocking my fastest miles, I stretched on my rooftop.

In 2014, I joined Black Roses NYC. I ran with a crew of runners. I thrived during track training sessions after work and half marathons followed by margaritas on Saturday mornings. I learned to love running in the streets, exhilarated by the pace of the city and the feeling that only we got to see it like we did.

But while the road running chapter of my life was in full swing, completely consuming me, something else was consuming me, as well.

In 2012, 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, was followed and killed in Florida by George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watch coordinator in the gated community where Trayvon was visiting relatives. Zimmerman felt he didn’t belong. He was charged with murder and acquitted for self-defense.

In August 2014, Michael Brown, age 18, was killed in Ferguson, Missouri. He was walking in the street and a police officer, Darren Wilson, didn’t think he should be. An altercation ensued. Brown’s friend said the officer started it by lunging through the window and grabbing Brown who tried to run away. The officer claimed Brown attacked him, trying to grab his gun. Darren Wilson was not indicted, and the argument was self-defense.

Every day I was learning names, a list I could recite in my head, and circumstances that I didn’t want to learn: Jordan Davis, Corey Jones, John Crawford III, Terence Crutcher, Keith Lamont Scott, Walter Scott, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Jonathan Ferrell, Renisha Mcbride, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Philando Castile. Black lives ended, shot down in the street, having been found guilty of no crimes. The Black Lives Matter movement solidified, protested, screamed, and cried, that this could not be overlooked, that this was systemic.

As an undergraduate at Yale University, I studied African American Studies and Film Studies, focusing on how stereotypical images of people of color impacted mainstream understandings of them. This tactic was propaganda and allowed for continued dehumanization and justifiable mistreatment. One of my favorite essays is called Can You Be Black and Look At This: Reading the Rodney King Video(s) by Elizabeth Alexander, which discusses the shared experience of witnessing violence. With the advent of cell phone videos, we now see “Rodney King-like” beatings and murders of black people at the hands of the police constantly.

What does it do to us as a community to have to witness this and to see nothing being done, to see that excused as justifiable? This isn’t happening to white people. We aren’t learning their names and mourning their deaths and sitting enraged and helpless while the perpetrators walk free.

It instilled a fear in me. Shortly after Brown’s death, I was running on Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, just blocks away from where I lived, on a hot summer day. If you know it, you know it’s a thoroughfare designed for easy recreation. It’s famous, designed by the same person who designed Central Park. The street has wide sidewalks of stone on each side, with bike lanes, and benches. I was wearing headphones, a sports bra, and shorts—typical summer running attire. Suddenly, fear washed over me. “What if a cop wants to stop me and I don’t hear them and they shoot me,” I thought. I pulled out my headphones. Then I stopped running. I couldn’t believe I was having these thoughts. I was allowed to be out running. Why this fear?

In my daily life, I encountered people who thought these killings were justifiable. At the time, I’d been managing a restaurant, and we had an incident where an undocumented worker from El Salvador spilled boiling tomato sauce on himself. I called the cops, despite other undocumented coworkers expressing fears. I climbed into the ambulance, giving the restaurant’s information to the paramedics, and translating for my coworker because he spoke no English. Later, my bosses inquired how much information I had given. I soon realized, they’d been trying to avoid having to pay for the hospital bills.

After the incident, an owner noted that I seemed distracted at work. I explained how yes, that and the death of Michael Brown, which had happened before the burn incident, had been on my mind. “No offense, but if I was out working and just trying to get home and do my job and some kids were walking in front of me and messing with me, I’d be out there hitting and stopping kids too,” he responded over the phone. I quit that week.

The words stuck with me. He said, “Hitting and stopping kids,” but killing them, murdering them is what he should have said. Even he—this white Brooklyn-born man, who loved rap music and graffiti, who hired black people and trusted them to run his businesses—thought these killings were justifiable.

This is America, and we live in a society where mollifying white fear is more justifiable than black lives. I wrote about this in detail recently, tracking this fact from slavery through modern-day lynching. And while my lived existence and my academic background focuses on the African American experience, I know this is not the case only for us, but also for so many historically and continuously marginalized groups.

People ask me all the time, What can we do? Do not go quietly.

The killing of innocent black people—at the hands of law enforcement, and by private citizens usurping the role of law enforcement—is not going to stop by chance. It isn’t happenstance, and it isn’t the fault of a few bad apples. Our country, by their lack of widespread protest, has said that this is justifiable.

We want to believe we live in a free and equal America, but it is time to stop lying to ourselves. This country is capable of making this change—American society has progressed from a country built on slavery and genocide to a country capable of electing a black president. People have looked ugly truths in the face and said, we must fight against this and make new and better truths.

Movements change because of tipping points. Public outcry can be the tipping point that makes a problem too great for those in power to stay in power without addressing it. But we have not yet reached this tipping point, because the truth of black death being justifiable is too hard for many people to look in the face.

So we look away. We pretend that 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones, shot in the head by police officer Joseph Weekly during a raid in Detroit, who was cleared of all charges in 2010, has nothing to do with Amadou Diallo’s killing in 1999. We don’t want to acknowledge that this is an ongoing problem.

If you believe that running is powerful, you have a tool that you can use to make change.

When Ahmaud Arbery was killed, the running community unified. I saw runners who aren’t usually very political running 2.23 miles in his honor. I saw people who don’t usually run posting up their 2.23 mile solidarity run.

We run for nonprofit organizations and incredible causes all the time. What if we were running to support social justice organizations with the same fervor? We raise millions to fight lupus and cancer, for suicide prevention, for issues we consider to be issues of public health. I believe that the inability for people to walk the streets safely, to run the streets for exercise without fear, is also an issue of public health.

Running is a statement and it can be a bigger one if we use it. Don’t run for Ahmaud once. Run for Ahmaud and Tamir and Michael Brown. Run for your friends who are scared, for their children so that they can run freely one day. Run for high school students right now, who might not ever consider going on a run after learning of the fate of Ahmaud Arbery. Run for them every Wednesday, or the first Thursday of each month. Make the acknowledgement of ongoing injustice a part of your reality, not just a sad story to be forgotten. Run for a better sport, a safer world.

Run like you are at risk, because you are if we don’t change this. Our freedom is more fragile than we think. And it grows more brittle if we can justify it being protected unequally. These deaths are not justifiable. And neither is our silence.