In 2011, 27-year-old Harvard graduate Sonia Vallabh got the worst news possible: she was carrying a genetic mutation that would almost certainly lead to a rare and fatal brain disease called fatal familial insomnia. The same genetic error – a single wrong letter of DNA in her “prion” gene – had caused the death of her mother the year before. But rather than despairing, she and her husband, Eric Minikel, ditched their successful careers in law and engineering and set out on a quest to find a cure. Seven years on, they have developed a treatment that they hope will slow or even prevent the onset of the devastating illness.

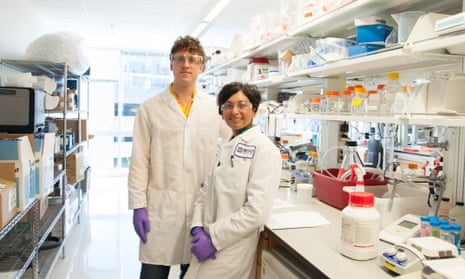

Sonia Vallabh

When did you first become aware your family was affected by prion disease?

It was a complete surprise. We didn’t have a known family history of this disease. It all happened really abruptly in 2010 when my mum became ill. She was 51 years old and healthy. Over the course of weeks there was a really sudden onset. It was like watching a time-lapse video. We’ve since learned that’s just the way this disease is.

In January she was healthy. By March she was really severely confused, unable to navigate the world alone and unable to get to the end of a sentence. And that continued at a rate that was really shocking.

Was getting a diagnosis a struggle?

If you don’t have a diagnosis, which we didn’t, we didn’t know whether this was something she could recover from or whether it was something she would be like for the next 30 years.

Should I be quitting my job and moving home? No idea.

In December we got a preliminary diagnosis of prion disease. That allowed the family to make a decision to take her off life support. But it was only after she passed away that we discovered that it had been genetic prion disease. That had not been part of the conversation before that and came as such a shock and a blow to us.

How easy was the decision to get tested?

For both of Eric and me, it was immediately obvious that I needed to get tested. We were sure we couldn’t go back to a place before we knew I was at risk. Maybe the coin would flip the right way, but if it was going to be hanging over our head for ever, we might as well find out.

A lot of people would agonise over that decision, but it seems as though your mind was made up to find out?

The worst time was the time when we were waiting and the worst day was when I found out I was at risk at all. We were waiting for two months after I sent in my sample. I woke up every day thinking about it. I was constantly flipping the coin, flipping the coin.

How did you feel, getting the positive diagnosis?

After we got the result, it was a crushing moment. But the recovery that came after that surprised me. We really did start to assimilate within a week or two to the new normal. In some ways, it was a relief to just know and to think, OK, now we figure out the next thing.

We heard this refrain of “There’s nothing you can do” [because there was no existing cure]. I have come to feel really strongly that that’s not the case. It has been really empowering to have this information. Last year, we had a daughter through PGD (pre-implantation genetic diagnosis). That was empowered through knowing my status. It’s not a bullet-proof procedure and it’s certainly very intensive to go through. We were so lucky and had a mutation-negative daughter.

You made a radical career change – how did that come about?

It all happened really fast. I was a recent law school graduate and I felt I needed to take a sabbatical to become as informed as I could about the disease. I took time away from my job and read papers and enrolled in a night class in molecular biology. Someone I came across said he knew of a lab that was hiring a technician full-time. That became my first job in science. Eric followed me a few months later. He’d been working as a transportation planner, but had a strong computer science background and pointed it over to bioinformatics.

Your next step was a PhD at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University. How did you approach your research?

We got some pushback, people saying your PhD is not the time to focus on your own scientific goals and your own disease. I see where they’re coming from, but it just wasn’t resonant with the place where we were psychologically. We were like: we just don’t have time.

Our job was to find the thing that would get there fastest, even if it’s not a Nobel prize-winningly novel idea. There are so many interesting questions in prion science that we didn’t pursue because we have to maintain focus on what will take us closer to a drug. We had a conversation at that time with Jeff Carroll. He’s a Huntington’s disease mutation carrier and scientist. He’s the original us.

Jeff introduced you to the company Ionis – how did your first meeting with them go?

We left with a lot of homework. A list of things that we would need to do to convince them to work on our disease. They said they could provide the antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) [a synthetic DNA-based drug]. We needed to show that ASOs change levels of prion protein in mouse brains and change their survival. We needed a biomarker if we’re thinking of treating humans down the road. The onus was always on us to show we can find the people [to participate in a trial]. We launched an online registry.

It’s not a finished story. We’re still doing different flavours of mouse studies. We’re still working on building the registry and launching a second wave of biomarker studies. But we’ve got sufficient data and confidence that we and Ionis were able to say, this drug looks like it is going to work. The time to start spreading the word about this is now. The first drug into the first patient might be within five years. We hope people will see a cause for optimism and a reason to get involved.

Do you and Eric work well together?

People say to us all the time: “Wow, I couldn’t work with my spouse.” That’s been critical because this has been so immersive. Having a partner in all of that made a huge difference. Certainly it gets stressful. One thing we’ve had to [work on] is taking small setbacks as small setbacks and not feel like our whole mission has been derailed. We tend to be out of phase with that.

How has your view of the future changed since your diagnosis?

What’s amazing to me is how optimistic we were in 2012 when we didn’t really have any basis. We didn’t really have anything to lose. We thought we’d throw ourselves at this as hard as we can.

I feel really lucky we’re finding more of a scientific footing and grounding for that optimism over time. Now we can see concrete reasons for optimism.

Eric Minikel

How did you cope with discovering Sonia carried the mutation for prion disease?

The hard part was finding out that Sonia was at risk. The floor just fell out from under me. It was devastating, I cried and cried and cried and knew things would never be the same again. It was unbelievably painful.

The test result was the worst news. We both called in sick the next day and tried to find out more about what a dominant genetic disease is. Stuff that I’d probably learned in high school biology and forgotten. At that time it never occurred to us that we would start to try and cure the disease ourselves.

How did Sonia react?

Sonia was really strong. I’ve seen this over and over again in our quest, but I still can’t believe how strong and fearless she has been. The silver lining of this experience is, I’ve got to see her in a whole new light. We’d been together nearly four years before we got this genetic diagnosis. I was madly in love with her, thought she was amazing, but I’ve got to see a whole new side of her. The ferocity with which she jumped into this, it was crazy.

What did you learn about prion disease in those early months?

The disease is caused by the misfolding of one protein, called the prion protein. Everyone has that protein in the brain and once it misfolds, it spreads to other copies. It’s like this domino effect where it spreads exponentially across the brain.

The one distinction is how that misfolding event comes about in the first place. Most people who die of prion disease have sporadic prion disease. A totally random misfolding event in the brain that triggers the cascade.

In a minority of people, it turns out these events are more likely to occur because of a genetic mutation. In most people, there’s something like a 0.02% chance that there’s ever going to be a misfolding. Someone like Sonia has a 90% chance that there’s going to be a misfolding event.

But this could happen at any time?

For Sonia’s mutation, there’s been a case in someone as young as 12 and someone has lived to 89 without developing any symptoms. It’s terrifying. We’re racing against a clock that we can’t see. We know we have to get the drug out as fast as we can before Sonia gets sick.

Together with Ionis, you’ve developed a drug that seems a good candidate. How does it work?

Ionis makes a class of drugs called antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs). They’re basically made of DNA that will bind to an RNA [messenger] molecule in our body. When it binds it causes an enzyme to come and cut it out.

The whole vision is that we know that prion protein causes this disease and so if you have less of it, that’s better. If you have mice with half as much of the protein, they take twice as long to get sick. If they don’t have any of it, they don’t get sick.

Prion protein is not crucial. In mice with this gene deleted, the mice are still healthy and viable and have normal lifespans.

Do you have a good network of other people affected by prion disease?

In 2013 we felt like we’d spent enough time coming to terms with it that we could go to conferences and meet other people who were affected. Now I find it really powerful to know that we’re not alone. It’s amazing how many of the same struggles other people have been through. 100% of people who have been through this disease went around looking for a diagnosis. That frustration is so prevalent. It’s disturbing in a way but it’s also reassuring to know it’s not just us.

You’ve achieved an amazing amount in such a short space of time.

Conversations like this are really important to remind me of that big picture. It’s really hard to look at one day of work or one week of work and be happy with what you’ve accomplished. Science is slow and frustrating. That is what powers me through the day-to-day work.

How hopeful are you for your and Sonia’s future?

I’m incredibly optimistic about the future. A lot of people have asked what do I think it would be like to fail. From very early on I’ve become very optimistic that we’re going to do this. I’m not willing to hand any victories to the disease. I feel in my heart we’re going to do this. I basically think we’re going to succeed; it’s just a question of how.