Director Yony Leyser calls queercore “a farce that became real”, while film-maker Bruce LaBruce labels it a respite for “the fringe of the fringe”.

LaBruce is uniquely qualified to make his claim. Thirty years ago, he and fellow Toronto artist GB Jones started what later became known as queercore, a fake movement that somehow morphed into a genuine one. “People thought that Toronto was the center of this hardcore movement,” says LaBruce in a new documentary directed by Leyser titled Queercore: How To Punk A Revolution. “But it was just me and two women who sat in their basement and churned out alternative publications and experimental movies.”

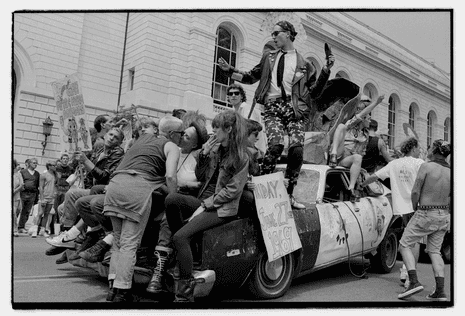

Yet they were clearly on to something. The primitive DIY projects they produced espoused a philosophy that drew on a long history of political and artistic subversion, one that located a connection between the radical roots of punk and the core insurrection of gay identity. In the process, they aligned two outlaw movements which, even back then, had already started to become domesticated and conforming.

“The original punks from the 70s, like Patti Smith and Iggy Pop, were all about breaking with everything that America was moving towards,” said Leyser. “They thought of the middle-class suburban couple with two kids, a job and a dog as a prison they were fighting against. And, in fighting it, they embraced gender-fluid, feminist and queer ideologies.”

The very term “punk” has roots in gay sex, referring to a man on the receiving end of anal intercourse in prison. But trying to make those connections in the 80s proved to be a daunting and risky task. While the freewheeling world of early punk embraced a wide range of sounds and sexualities, by the start of queercore it had already ritualized into the macho hardcore trend, whose bands and fans started to look and sound increasingly alike. Similarly, the mainstream gay community was, by then, presenting an exponentially more hetero-normative image. In the film, LaBruce talks about being rejected by two subcultures before he started queercore. “I would get beat up for ‘looking queer’ at hardcore shows,” he said. “And I would get kicked out of gay bars for wearing swastika earrings.”

Leyser also fell between two worlds as a punk-loving gay teen growing up in Chicago in the 90s. He found the first inklings of a connection between gay and punk cultures through the work of untamable artists like film-maker John Waters and writers like Jean Genet and William Burroughs (whom Leyser had made an earlier documentary about). “Often when history gets written, these outlaw elements get overlooked,” the director said. “They brush the dirt under the rug rather than celebrate it. In my film, Bruce LaBruce talks about embracing the criminality of gay sexuality, which is what Genet had done.”

The early queercore artists not only spread their gospel through zines and films, but also in art and music, all of which were inspired by earlier work from the Dadaists, the Situationists and the Sex Pistols. LaBruce’s clearest role models were seminal John Waters films like Multiple Maniacs and Pink Flamingos. “Waters did the full DIY aesthetic,” Leyser said. “He took all of his crazy friends and put them in front of a camera doing the most extreme things he could think of, like Divine eating dog shit or saying lines like: ‘The life of a heterosexual is a sick and sad existence.’”

Waters, who appears in the film, also helped the director get financing for the project. An equally key role model for the movement, within the music world, was gender-transcending glam/punk rocker Jayne County. Humor plays a key part in both artists’ work, as it does in later queercore projects. “Bruce LaBruce used humor as a weapon in his films to critique society, just like Burroughs used satire as the sharpest knife to cut through society’s facade,” said Leyser.

LaBruce and Jones seeded the movement through their magazine, JD, which, depending on their mood, they would claim stood for JD Salinger, James Dean or Jeffery Dahmer. Their efforts spawned later zines, scenes, labels and bands in Chicago, San Francisco, Edinburgh and London.

There was also a porn connection. In the late 80s, Jim Yousling, editor of the LA-based gay skin magazine In Touch, regularly featured rockers like the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Henry Rollins in homoerotic photo shoots and interviews well before they became national names.

In New York in the late 80s, Dean Johnson and his band, Dean and the Weenies, created Rock’n’Roll Fag Bar, inspiring the later NY club Squeezebox, co-curated by the musician who went on to write the glam-rock musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch. In a seminal crossover moment, Green Day invited queercore band Pansy Division to open on their 1994 breakthrough tour. Around the same time, queercore influenced the riot grrl movement, which has only widened its influence in the years since.

Even at its most successful, queercore has never come close to intersecting with the gay or punk mainstream. Today, it’s at even greater odds with the talking points of LGBT politics, which center on what can be seen as a heteronormative agenda – getting married, having children and serving in the military. Many speakers in the film decry this “gay orthodoxy”, underscoring the fact that queercore has as much to do with sensibility as sexuality. “Ultimately, queercore relates much more to the punks than to the gay movement,” Leyser said.

Even today’s “gay music” has become more mainstream, with the rise of such fresh-faced “queer pop” artists as Troye Sivan and Kim Petras. Leyser sees another example in Simon Vance Law, who has a hit in Europe with Gayby, which celebrates gay parenthood. “It’s so boring,” the director said. “If it was just him singing to his wife about taking care of their kid, no one would listen. The only value it has is that he’s gay, so straight people can think, ‘Oh that’s so sweet: gay people can be just like us.’”

At the same time, more radical queercore artists such as Ssion and Arca are getting increasing media attention. And Leyser cites artist/activist groups such as Germany’s Peng or Russia’s Pussy Riot as keepers of the queercore tradition.

It’s notable that the movement, like punk in general, has managed to retain its radical edge 30 years after it started. “Punk has now greatly outlasted hippie culture because it allows people to have a catharsis,” Leyser said. “With hippies, people related to the free love part, but its peace and love message didn’t provide the catharsis that Western society really needs – which is to provide a good place to say: ‘Fuck you.’”

Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution is released in New York and LA on 28 and in other US cities throughout October