What Does Trump Actually Think About Gun Control?

The president’s suggestions range from arming teachers to Obama-style background-check regulation.

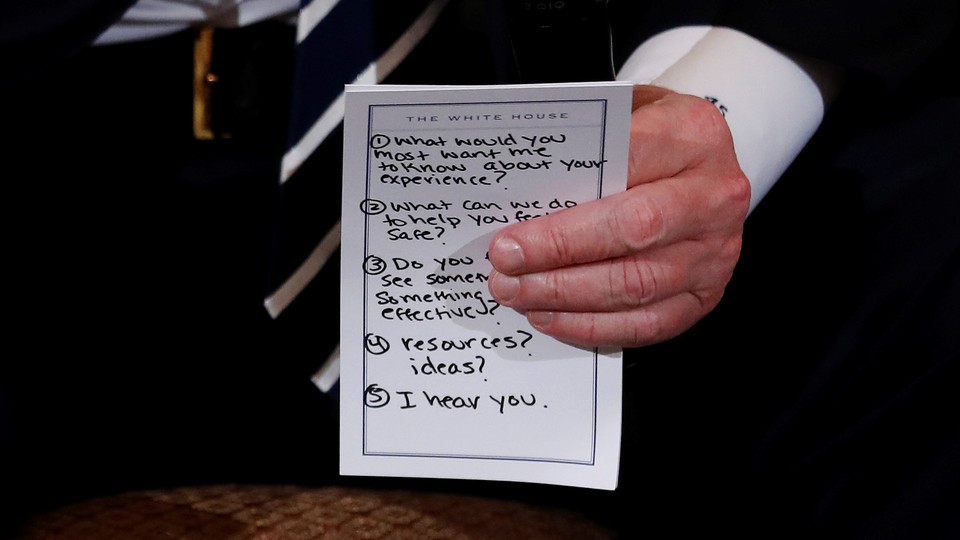

Crises are crucibles, bringing out a leader’s core characteristics. The aftermath of the shooting last week at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, has thrown two sides of President Trump into sharp relief.

Over the course of 48 hours, Trump has suggested a variety of possible responses to gun violence in schools. Some of them look like the product of the independent, unconventional politician some people had hoped for—willing to buck partisan orthodoxies about gun control in favor of policies that he sees as common sense, and which draw broad public support: tighter background checks, mental-health restrictions, higher age limits for buying rifles. Other suggestions show the other Trump: An impulsive politician who quickly grabs onto ideas without thinking them through, and finds it hard to resist throwing red meat to his base, like suggesting the arming of teachers. They also display his tendency to see the world in Manichean terms, and his emphasis on heroic individuals rather than systemic forces. The clash between these two Trumps is a central tension of his presidency. Thus far, it is the second set of tendencies that has triumphed over and over. Will the gun debate end any differently?

During a Tuesday meeting at the White House, Trump appeared to endorse an idea circulating in conservative media to arm teachers, as well as eliminating gun-free zones.

It’s called concealed carry, where a teacher would have a concealed gun on them. They’d go for special training. And they would be there, and you would no longer have a gun-free zone. A gun-free zone to a maniac—because they’re all cowards—a gun-free zone is, let’s go in and let’s attack, because bullets aren’t coming back at us.

And if you do this—and a lot of people are talking about it, and it’s certainly a point that we’ll discuss—but concealed carry for teachers and for people of talent—of that type of talent. So let’s say you had 20 percent of your teaching force, because that’s pretty much the number—and you said it—an attack has lasted, on average, about three minutes. It takes five to eight minutes for responders, for the police, to come in. So the attack is over. If you had a teacher with—who was adept at firearms, they could very well end the attack very quickly.

This is classic Trump: He has quickly fastened on to something he heard on cable TV, and meanders through it, promising to consider it, without quite committing. The idea doesn’t seem all that well-thought-out. There was an armed policeman at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School the day of the massacre, and it didn’t prevent the massacre. There were multiple armed people in Las Vegas during the October 2017 massacre there. Some firearm experts quickly argued against the president’s idea, noting the increased risk of accident and saying that even highly trained teachers would be unlikely to increase safety while contributing havoc. Even if guns could end massacres sooner, there’s little reason to believe they’d be much deterrent, since many school shooters are killed or kill themselves. Beyond that, questions like the arming of teachers or handling of gun-free zones are state or local issues, beyond the control of the federal government.

The vision of school shootings as simply a good-versus-evil conflict, and one in which a heroic figure can make all the difference, reflects Trump’s general approach to policy in general: “I alone can fix it.” He tends to eschew complicated solutions and look for how a single figure can change everything, a tendency that has collided with the ways of Washington and produced little substantive change.

In any case, Trump walked the idea back Thursday morning, sort of:

I never said “give teachers guns” like was stated on Fake News @CNN & @NBC. What I said was to look at the possibility of giving “concealed guns to gun adept teachers with military or special training experience - only the best. 20% of teachers, a lot, would now be able to

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 22, 2018

....immediately fire back if a savage sicko came to a school with bad intentions. Highly trained teachers would also serve as a deterrent to the cowards that do this. Far more assets at much less cost than guards. A “gun free” school is a magnet for bad people. ATTACKS WOULD END!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 22, 2018

....History shows that a school shooting lasts, on average, 3 minutes. It takes police & first responders approximately 5 to 8 minutes to get to site of crime. Highly trained, gun adept, teachers/coaches would solve the problem instantly, before police arrive. GREAT DETERRENT!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 22, 2018

I will be strongly pushing Comprehensive Background Checks with an emphasis on Mental Health. Raise age to 21 and end sale of Bump Stocks! Congress is in a mood to finally do something on this issue - I hope!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 22, 2018

Jonathan Chait aptly summarized that chain of argument as, “I never said give teachers guns, but it would be awesome.”

Indeed, Trump continued to flesh out the idea later on Thursday. “I don’t want teachers to have guns, I want certain highly adept people, people that understand weaponry, guns, if they really have that aptitude, because not everybody has an aptitude for a gun, I think a concealed permit for teachers and letting people know there are people in the building with a gun, you won’t have, in my opinion, you won’t have these shootings,” he said. “Because these people are cowards. They’re not going to walk into a school if 20 percent of the teachers have guns. It may be 10 percent, it may be 40 percent.”

He said that he’d want to give bonuses to teachers who carried concealed weapons. “You can’t hire enough security guards,” he added. He also said that schools needed to take “offensive measures.”

Strangely, however, Trump also argued against preparedness for shooters, saying that active-shooter drills are bad for children. “Active-shooter drills is a very negative thing, I’ll be honest with you. If I’m a child, I’m 10 years old and they say, ‘We’re going to have an active shooter drill,’ I say, ‘What’s that?’ ‘Well, people may come in and shoot you.’ I think that’s a very negative thing to be talking about, to be honest with you. I don’t like it.”

Trump, a prolific merchant of violent rhetoric, also complained that young people are too violent-minded. He said that a military base is “frankly no different” from a school, because both are gun-free zones.

If Trump’s arguments in favor of arming teachers are unrealistic and unwise, and his arguments against school preparedness nonsensical, some of his other ideas have been surprising for different reasons. Take, for example, the proposals to ban bump stocks, tighten background checks and focus on mental health, and raise the age to buy rifles from 18 to 21.

It’s unclear how effective these measures would be in stopping shootings like the one in Parkland, Florida. School shooters have obtained rifles despite being under age; many shooters were not diagnosed with mental illnesses.

Yet politically, these proposals could practically have come from Barack Obama—and in fact the idea of tightening background checks and using assessments of mental health as a way to reduce access to guns are ideas that Obama proposed. The National Rifle Association has cautiously supported a bump-stock ban, but it opposes raising the age for buying a rifle. But on Thursday, Trump expressed little concern, saying he thought the group would come around to his view.

“I don’t think I’ll be going up against them,” he said. “I really think the NRA wants to do what’s right. I mean, they’re very close to me, I’m very close to them, they’re very, very great people. They love this country. They’re patriots. The NRA wants to do the right thing.”

It’s possible the NRA needs Trump more than he needs them. The organization endorsed him early and heartily, despite his spotty record on guns, and now he’s bigger than it is. As president, Trump can defy the NRA in a way that other Republican politicians cannot.

This is just the sort of independent, non-dogmatic policy approach that optimists hoped Trump would bring to the presidency. Unburdened by a long history of donations or of ties to the Republican Party, and given his own frequently shifting policy ideas over the decades, Trump seemed like a candidate who might shake up the policy consensus. Pushing gun regulations that are deeply unpopular inside the GOP but popular with the electorate overall would fulfill this hope.

Don’t count on it, though. More consistent than Trump’s obsession with heroism, his binary worldview, and his indifference to orthodoxy has been his lack of follow-through. Whatever Trump says now, the chances are strong that he loses interest or simply doesn’t have the fortitude to push through any serious policy changes in the wake of Parkland.