Saman Alavi is often asked why she chooses to live at home with her mother and two siblings. Most people who prod her about it assume she’d be “tearing her hair out.”

But in fact, the 28-year-old really enjoys living at home. Alavi genuinely likes her family (her siblings are close in age and share similar taste in Netflix picks), she doesn’t find her commute taxing, and the hour-and-fifteen-minute trip out of Toronto into Milton gives her a chance to unplug from her stressful work life.

And when she compares the $1,000 she spends on commuting to what an “adult” apartment in Toronto would cost her, it’s clear she’s made the right choice.

“For me, it turned out to be a purely financial decision,” says Alavi, a program manager at Top Hat.

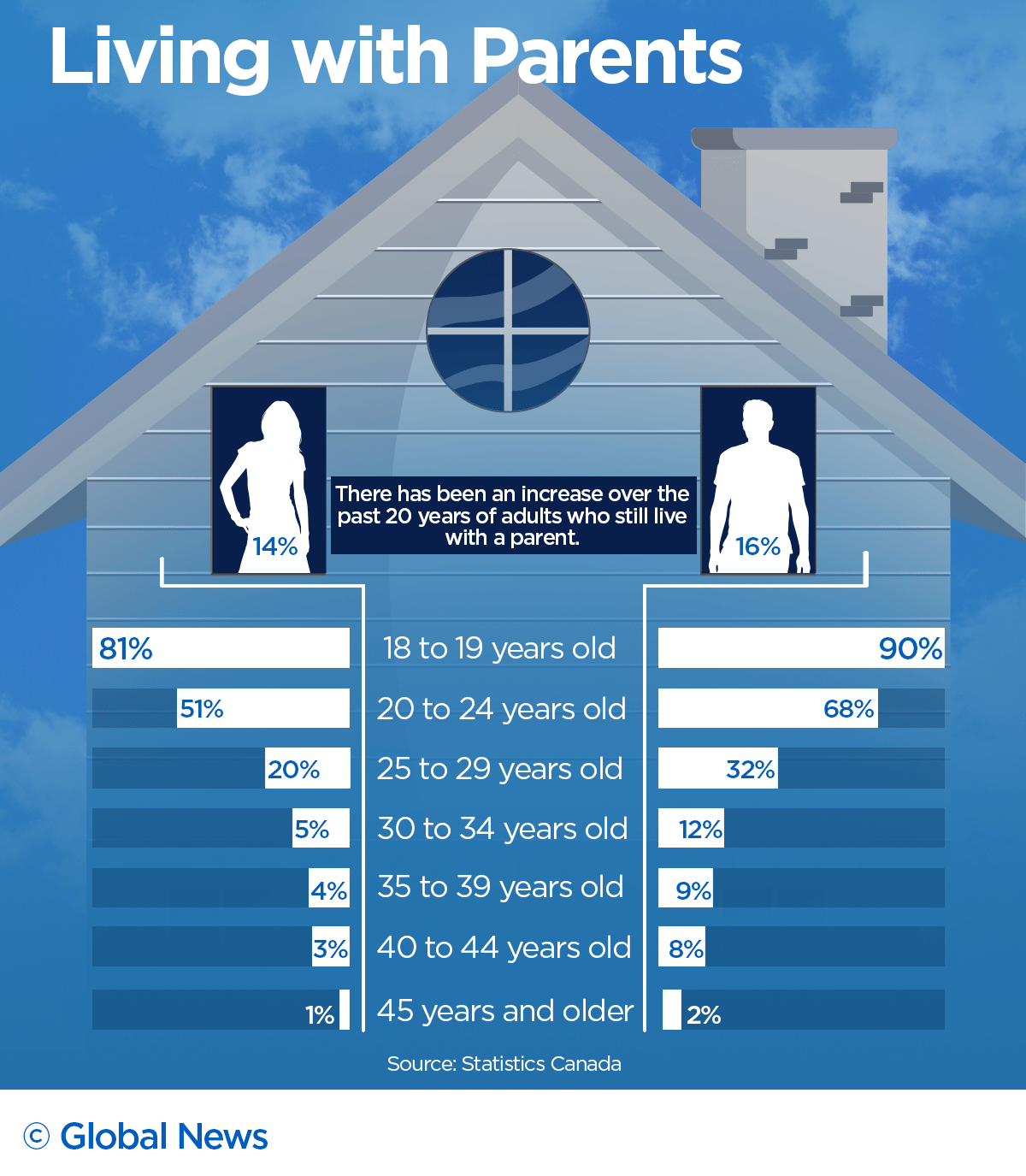

She’s one of a growing number of adults who are living at home, according to new data released by Statistics Canada. The number of adults living with their parents doubled between 1995 and 2016, and Alavi is part of the age group that saw the biggest jump: 25- to 29-year-olds. While in 1995, one-in-five adults in that age group lived with their parents, by 2016 that number became one in three.

While adults living with their parents may be motivated by high levels of student debt and skyrocketing housing prices, as Global News’ Erica Alini has written, it can also be seen as a return to a historical norm. And for others, it’s a cultural norm.

- Life in the forest: How Stanley Park’s longest resident survived a changing landscape

- ‘Love at first sight’: Snow leopard at Toronto Zoo pregnant for 1st time

- Carbon rebate labelling in bank deposits fuelling confusion, minister says

- Buzz kill? Gen Z less interested in coffee than older Canadians, survey shows

As someone with Pakistani parents, Alavi is part of the 21 per cent of adult South Asians who live with their parents, compared to nine per cent of adults Canada-wide.

She doesn’t relate to the stereotype of a stifling cultural obligation keeping her tethered to her parents’ home — Alavi lived away all throughout her undergraduate and graduate studies. For her, there was comfort in knowing there was no cultural expectation to leave.

“In our community, there’s no stigma attached to coming back and staying with your parents, so you don’t feel that pressure to be independent as other communities do,” says Alavi.

She definitely sees advantages to being independent, but for her, it’s the decision that makes the most sense. She is married to a medical resident who is based in Boston, and eventually will move to the U.S. to be with him. While her move isn’t imminent, living at home gives her flexibility. And in the meanwhile, Alavi can put more away toward her financial goals: getting rid of her student debt and saving for a down payment on a home.

In housing markets like Toronto and Vancouver, it’s an unsurprising decision: Owning a home seems impossible, while rents appear to be ever-climbing as vacancy rates remain low.

Arnold Lam is a 25-year-old investment analyst who has opted not to buy or rent in the Vancouver area. Like Alavi, Lam is part of the 74 per cent of adults over 25 who live with their parents who have jobs. He’s a second-generation Chinese-Canadian living with his parents in Richmond, B.C., and has been working full-time since he graduated two years ago. As a man, he’s part of the 56 per cent of 25- to 34-year-old men living with their parents, compared to 44 per cent of women in the same age bracket.

“I enjoy staying at home,” he admits. And for good reason: his standard of living is pretty good. He can take the train into work, and his girlfriend, who also lives with her parents, lives conveniently just down the street from him. Not struggling to make a mortgage payment means there’s more money for them to make weekend trips to Whistler and nights out.

Enjoying a certain standard of living doesn’t mean Lam’s blowing his salary on avocado toast — as an investment advisor, Lam is strategic about how to grow his money. “Instead of spending it on rent I’d rather invest it and see what that will become,” he says.

And investing it in a mortgage isn’t an immediate goal for him either, representing a “type of stress I don’t necessarily need,” he says. But he and his girlfriend are hoping to buy in the next couple of years.

WATCH: Money 123 — Finding the right financial advisor for you

He’s comfortable with his situation partly because, also like Alavi, his parents don’t expect him to move out any time soon. Apart from those of South Asian descent, Chinese-Canadian adults are the most likely to live with their parents. He’s also comfortable staying at home because it’s not a one-way exchange — whether it’s car-pooling or shovelling snow, Lam likes being around to help out where he can.

And once he moves out and gets settled, if his parents ever need to move in with him, Lam says it’s definitely an option.

As a financial advisor, Lee works with many families from South Asian, Chinese and Iranian backgrounds on how to make this work. Lee sees some of this movement as a sign of Canada’s aging population at large. The latest StatsCan data shows growth in the number of adult children 35 and older living with parents, which may be reflecting an increase of adult children taking in elderly parents. Of those aged 40 to 44, for instance, eight per cent were living with a parent in 2016, compared to three per cent in 1995.

“They’re jumping in to assist,” says Lee. He works with two kinds of clients: those creating separate units in their homes for elderly parents to move into and others who pool their resources for a joint, multi-generational household.

Multi-generational households are more common with South Asian clients, Lee said. The latest data on households showed that 10 per cent of adults that live with their parents also had a child live with them. Households where three or more generations live together are on the rise across the country, according to StatsCan, with one in four people in Brampton living such a household.

Lee, in his forties, is also considering options for his own parents as they age.

“I’m Asian — we were brought up to take care of our parents,” Lee says plainly. “But even in Western society, everybody wants to make sure their parents are taken care of.”

Comments