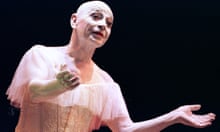

Lindsay Kemp, despite turning 80 this year, performed continually with his company of young dancers. He had lost some flexibility because of a back injury and was blind in one eye – which he kept secret – but his artistry could touch people so profoundly that just being in his presence cast a spell.

He would talk of putting people into a trance but, more than that, he had an ability to create a moment on stage filled with light, music, a painterly sense of the visual, and movement that would expand your imagination. He inhabited Prospero’s magic island where tragedy and comedy collided. His stage imagery required genius.

He often talked of reaching the back rows with his (piercing blue) eyes, and in his classes he taught his beloved students how to tap into a truth inside themselves – a sadness or a joy – that he could transform into one slow movement that could fill an amphitheatre.

His passion for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, kabuki, butoh, silent film, opera, music hall, flamenco and Lorca drew the world’s leading artists to him: Rudolf Nureyev, Marcel Marceau, Joan Miró, Federico Fellini, Sir Alec Guinness and of course, Kate Bush and David Bowie.

He caused a sensation the world over with his production Flowers, based on the novel by Jean Genet. Bowie came night after night to sit, watch and be beguiled. In the 1960s, Bowie joined Lindsay’s company and played Cloud in Pierrot in Turquoise.

Bowie immersed himself as Lindsay’s student and lover, intrigued by the jazz musicians in paisley kaftans, The Incredible Orlando (Jack Birkett) and the flurry of ladies of the night who shared a staircase with Lindsay’s Berwick street apartment. Lindsay’s flatmate at that time was Steven Berkoff.

When Lindsay took his own production, Onnagata, to Japan in the 1990s, the crown princess entertained him in the Imperial Palace.

Lindsay’s gifts as a teacher should not be underestimated. Kate Bush first attended his classes, as did Mick Jagger and Bowie, at the Dance Centre in Covent Garden, the hub of London’s dance world until the 70s, and he proudly told me “all the secretaries came too, in their lunchbreaks”.

I remember one story told to me by John Spradbery, his father figure and the lighting designer for the Lindsay Kemp Company: Jean-Louis Barrault – the delicate mime from Les Enfants Du Paradis – came to see Lindsay at the Drury Lane Arts Laboratory. He had to wait until 2am to see him perform because the Hells Angels had commandeered the space for a wedding.

Lindsay was brilliantly funny offstage. He was a Puck-like personality in real life: completely free, astonishingly smart, well read and passionate about social issues. He also could be a tyrannical perfectionist, sometimes expressing his displeasure or jealousy in improvisations on stage that would leave his actors provoked or in confusion. His life on stage was his most intense reality, his real life – and one that he might create at will.

In 1977, Lindsay created one of his masterpieces, Cruel Garden, in collaboration with Chilean composer Carlos Miranda and choreographer Christopher Bruce for Ballet Rambert. Lindsay had studied with Marie Rambert and she had hit him over the head with her stick, saying he should go back to the north where he came from. Cruel Garden is now considered Rambert’s greatest work.

Lindsay grew up in wartime South Shields, losing his father on the ship HMS Patroclus and his five-year-old sister to meningitis before he was born. He became his mother Marie’s child replacement. She was a talented woman, always immaculately made up, even perfumed, while the other mothers in her neighbourhood wore tea towels tied round their hair.

Marie wore bright red lipstick and a cape with a scarlet lining. Lindsay’s childhood friend Yvonne Litchfieldtold me about the plays he would make up with them. He performed the song Little Old Lady in his modest garden at Talbot Road at the age of six, charging all the local children a penny, and with any money he would make, Yvonne and Lindsay would rush to buy greasepaint.

Lindsay lived the hard, rough-and-tumble life of a performer. He would never compromise his work, and this meant that while his work was revolutionary, it sometimes left him penniless. His collaborators David Haughton, Daniela Maccari, Carlos Miranda, Christopher Bruce, Nuria Moreno, François Testory, Robert Anthony, David Meyer and Sandy Powell kept him going and devoted much of their lives to his work.

Lindsay thought often about his father, the drowned sailor, and sailors permeated his drawings, his dreams and his productions. One of his favourite sayings was “Seagulls are the souls of drowned sailors.” He was not melodramatic about death; he wanted to create as much as he possibly could before he died.

- This article was amended on 26 August 2018, to correct the name of the part that David Bowie played in Pierrot in Turquoise