“Australia’s Prime Minister Mr Harold Holt is missing.”

They were the words that echoed from television sets and radios across Australia on December 17, 1967 – the day Holt stepped into the surf at Cheviot Beach near Melbourne and was never to be seen again.

The Australian leader was presumed drowned and a memorial service was held in his honor, attended by world leaders including UK Prime Minister Harold Wilson and US President Lyndon Johnson.

But his body was never found, leading to a range of ever-more ridiculous conspiracy theories, including one book which claimed he had been taken by a Chinese submarine.

Fifty years after his disappearance, Holt’s lengthy career as a progressive and ground-breaking Australian politician has been completely overshadowed by the mysterious nature of his death.

“The conspiracy theories have become so well-known and almost part of Australian folklore on their own,” Tom Frame, Holt biographer and director of the Public Leadership Research Group at the University of New South Wales’ Howard Library, told CNN.

“I think none of us would want our death to overshadow our life.”

‘First of Australia’s modern prime ministers’

Holt became Australia’s Prime Minister in January 1966, only two years before he vanished.

He’d been a loyal minister under the country’s longest-serving leader, Sir Robert Menzies. Menzies was a stuffy Anglophile who could not have been a bigger contrast to the younger, 59-year-old Holt.

“He was a breath of fresh air,” John Warhurst, emeritus professor of politics at the Australian National University, told CNN.

“He was younger (than Menzies), he was renowned as a very stylish, progressive man … Viewed from today, he was the first of the modern Australia prime ministers.”

Despite his relatively short time in office, Holt secured a series of significant achievements including switching Australia’s currency to dollars and cents from the complicated pound and pence system.

The other landmark of his time as a leader was the historic 1967 national referendum, which paved the way for indigenous Australians to finally be counted among the country’s population.

Frame said Holt was also one of the first politicians to work to end the infamous White Australia policy, which severely restricted immigration from non-European countries, and to reach out diplomatically to his nation’s Asian neighbors.

“He could see no argument for excluding Asians (from the country) … I think he broke down the view, gradually, in Asia that Australia did not want to be a part of the region,” he said.

It wasn’t only Asia that Holt wanted Australia to move towards. As Prime Minister, he built a close personal friendship with then-US President Johnson, famously declaring at the White House during a visit he was “all the way with LBJ” in the early stages of the Vietnam War.

“He wanted more US involvement in Asia and, because he had a good, personal relationship with Johnson, he tried to use that to cajole, encourage and entice to Americans to be part of Asia,” Frame said.

‘I know this beach like the back of my hand’

The day Holt vanished was hot and humid Sunday, perfect for a swim.

Before lunch on December 17, 1967, Holt decided to head to the local beach, close to the holiday house he owned at Portsea on the Victorian coast.

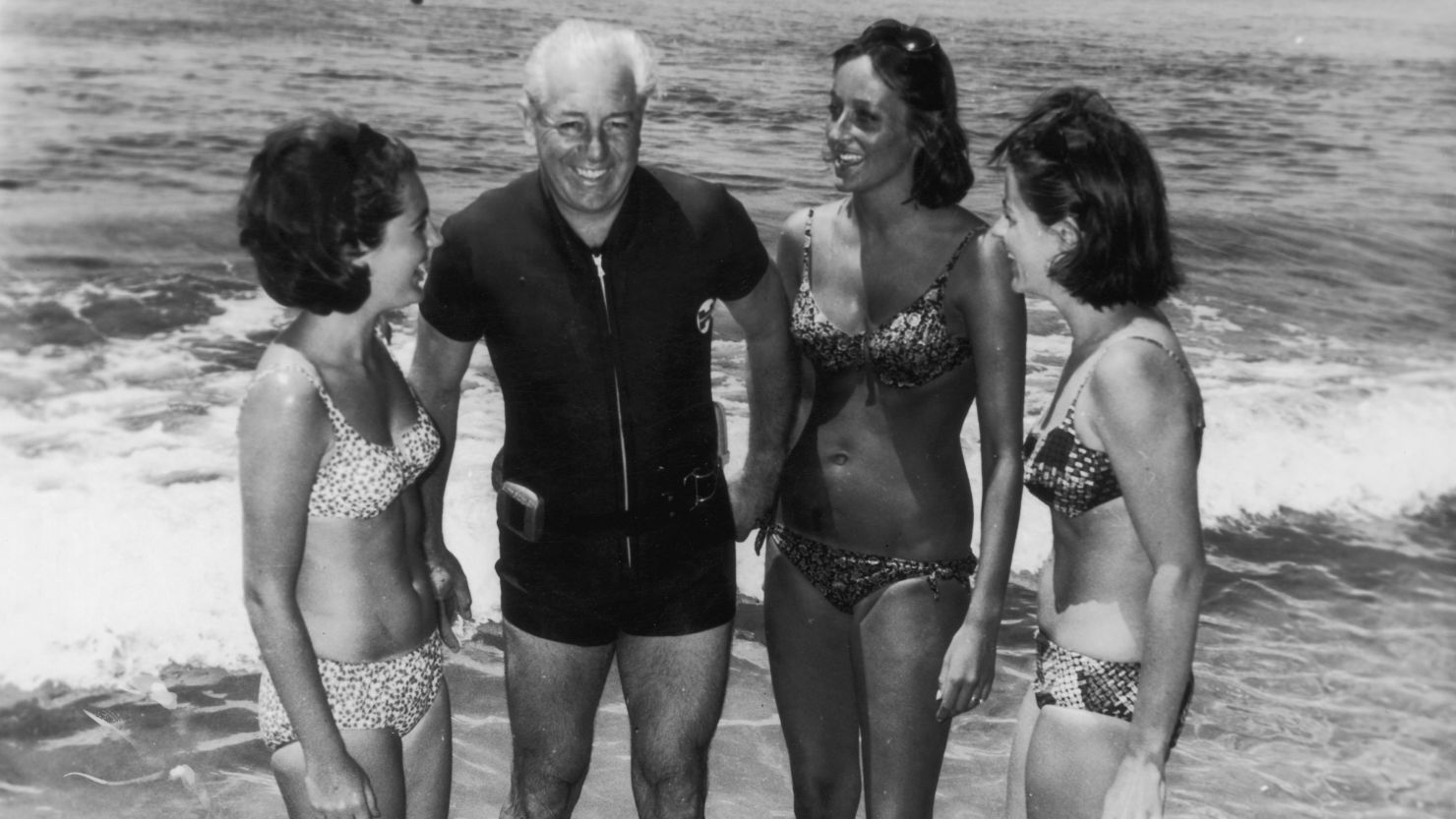

“There was an around-the-world sailor who was sailing into (Melbourne’s) Port Philip Bay, and they went to see him. He (Holt) was there with a lady friend and couple of younger house guests,” Frame said.

Holt was in many ways the quintessential Australian man – gregarious, sporty, a man with an appetite for life. He enjoyed diving and spearfishing although he wasn’t a terribly strong swimmer, according to Frame.

But the Prime Minister wasn’t in perfect health. He’d just had shoulder surgery and on Friday had been told by his doctor to “take it easy” after the operation.

“So he played tennis on Saturday and went near the water on Sunday. So it was against doctor’s orders,” Frame said.

Witnesses on the beach told police the tide was unusually high with a strong undercurrent that day. Some said it was the highest they’d ever seen it.

Despite that, Holt began to swim farther from the beach, into deeper water, a 1968 police report said.

One of the last things Holt had said to the group before he went into the water was, “I know this beach like the back of my hand.”

“(One witness said) she had watched Mr Holt continuously from the time he entered the surf and she saw the water become very turbulent around him very suddenly and appeared to boil and these conditions seemed to ‘swamp on him’,” the report described.

“He was not seen again.”

Drowning, suicide or Chinese submarines?

Australia was stunned at the news of their missing prime minister.

“I think after the assassination of US President John F Kennedy most people thought world leaders would have a security detail who would not be far away and, if he got in any difficulty, would help him out,” Frame said.

Amateur sleuths, police and even the Australian army descended on the beach in an attempt to find the missing leader, or at the very least his body.

The search had involved up to 300 people at times but was finally called off on January 5.

No trace of Holt was ever found – all that was left was his pile of clothes sitting on the sand at Cheviot Beach.

His disappearance made Holt’s death part of Australian folklore, and provoked furious debate.

Warhurst said there was wild speculation in the media that Holt had committed suicide, distraught over an allegedly fractious marriage or worn out from his job. Police in their 1968 report found this was highly unlikely.

Other theories had a more international flavor.

“(Some claimed) there was some sort of foreign power involved, that he’d been picked up by a Russian or Chinese mission and been whisked away against his will,” he said.

There was even a widely scorned book, titled “The Prime Minister Was A Spy” by British journalist Anthony Grey, which alleged Holt had been a Chinese spy, and had evacuated to a Chinese submarine from Cheviot Beach at the end of his mission.

“None of them have any evidentiary basis whatsoever… they do not hold water, they do not make sense,” Frame said.

“The most simple, straight forward explanation is he just drowned, that’s it, and people thought ‘prime ministers can’t do that’.”

Holt’s legacy

Holt’s disappearance sent the governing Liberal Party into turmoil, resulting in a series of short-term, ineffective leaders and eventually the return of the Labor Party to government in 1972, after 23 years out of government.

The Liberal Party itself did not fully recover from Holt’s death, according to Warhurst, until 1975 when future Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser took control.

For Australians, Holt’s brief time in office was massively overshadowed by the mystery of his death. Frame said he wanted to write about Holt because he felt the leader had been forgotten by history.

“I think if this anniversary does anything, (I’d hope) it’d lead Australians to consider his life a bit more rather than picking over his death,” he said.

Years later, Australians would honor their missing Prime Minister in a fashion befitting the country’s famous laconic sense of humor.

They named a swimming pool after him.