Growing up in London, there was a house I was fascinated by. It looked like a mini castle with a tower; red-bricked and handsome, a portal to another time with its stained-glass windows. Back then, I had no idea who lived there. Later, I discovered it belonged to the guitarist and music producer Jimmy Page, erstwhile of Led Zeppelin. I knew I had no hope of ever stepping inside. But life can throw some crazy stuff at you and three decades later, I am invited to visit. I tell Page all of this before he has even fully flexed the door on its hinges, “Well I’m so glad you came then,” he smiles, giving me a hearty handshake.

The Tower House actually has two front doors: the half bevelled-glass street door which leads into a mosaic lobby and the actual house door, adorned with brass sculptures showing the Ages of Man. Then, the only way I can describe what happens next is: imagine going to a party and all your best friends are there wearing the most opulent clothes of their lives, and they come and say hello all at once, and for a moment, you are so giddy you can’t compute. This is what entering the Tower House is like.

It was designed by the self-styled “art architect” William Burges between 1875 and 1881, in the 13th-century French Gothic style. Burges was well travelled, meticulous about research and detail, uncompromising in his use of materials, obsessed with the Middle Ages and was a skilled metalworker, jeweller and designer before he became an architect. He ran with an arty set: Leighton, Rossetti, Burne-Jones et al; was sociable, chronically myopic and even his best friends described him as ugly. He had quite a sense of humour and was absolutely not a cheap architect. Everything he’d ever learned and loved went into Tower House because it was to be his home.

Sadly, he was only to live at the house for three years. He died aged 53 in his red bed in the Mermaid Room on the first floor, under painted friezes of waves and swimming fish, and a ceiling of gilt stars studded with convex mirrors. He was next to his painted wardrobe which Page managed to buy back and return to the spot Burges intended it for. (Much of the house’s contents were sold off in 1933.)

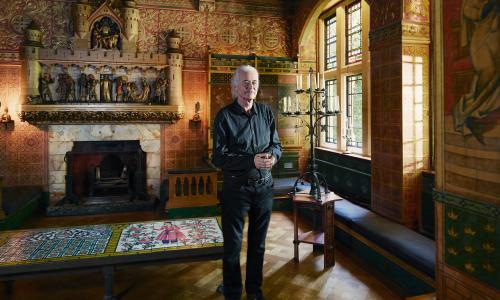

And here I am now, standing with Page (dressed entirely monochromatically) in the double-height entrance hall, on a mosaic floor depicting the combat between Theseus and the Minotaur, trying to take it all in.

The principal rooms in the Tower House all have themes (Time, Love, Literature) and tell a story; every room has stained-glass windows, elaborate carvings, frescoes, friezes and if there is a surface that can be embellished or adorned, in the utmost complexity, using the finest of materials, it will be. The chimney pieces are imposing and carved with 3D figures; the one in the library depicts the Principles of Speech in Caen stone.

The hall’s theme is Time, with giant, almost life-size frescoes depicting the sun and moon, and stained-glass windows symbolising the seasons. The ceiling shows the constellations at the exact time Burges moved in. A stone gallery above links the upstairs bedrooms and overlooks the entrance hall. Page says he first viewed the house, back in 1972, in a dim evening light, and it “captured my heart”.

The drawing room and library, where Burges entertained his pre-Raphaelite friends, are off the entrance hall. Page bought the house from the actor Richard Harris (John Betjeman had it before him) and when first viewing it, Harris’s Camelot throne was still in the library.

The library walls are lined with richly painted Burges bookcases which now house Page’s books. On the ceiling are the founders of law and philosophy. The windows depict the arts and sciences. The drawing room’s theme is Love, and a medieval Cupid is painted on the ceiling.

“Is your house always this tidy?” I ask. “I always try to keep it really tidy,” he says, “but at the moment I think it’s pretty untidy.” (It isn’t.) Page has a cleaner twice a week (“I’m guessing it’s not about spraying wood Pledge around?” I ask. “No,” he replies) and a regime of maintaining the house. It was Grade I-listed in 1949 and its interiors are important and fragile. Page describes how, periodically, things such as the walls in the hall need scaffolding and sugar-soaping by specialists. Everything is meticulously well looked after. I think the National Trust has nothing on Jimmy Page.

I am particularly interested to see how the kitchen works in a house like this, but Page won’t let me see because “It’s out of bounds, it’s untidy.” I beg until it’s unseemly; he doesn’t budge. (I visit one of the “toilet facilities” later which is all dark blue tiles and William de Morgan fish borders.)

The spiral stairs are in the tower. On the first floor, next to Burges’s old room, is the guest room: the Butterfly Room, a blaze of golds and reds, with a heavily decorated ceiling of butterflies and a deep frieze of plants and flowers.

The second floor, less elaborate, houses two nurseries (although Burges never had children). The day nursery – with a theme of Jack and the Beanstalk – has the terrifying giant coming out of the chimney. The night nursery is slightly more benign with grotesque monkeys.

We descend the stairs to the dining room which is dominated by a giant circular zodiac table, originally commissioned by Harris. Page is excited to point out that the table is a reflection of the design in the enamelled iron ceiling. Page loves the table, his last book was done on it.

Has Page always been attracted to complicated houses? He ponders and then tells me to hang on while he finds a picture of the first house he bought. “I found it in the Exchange and Mart,” he says. It was a boathouse in Pangbourne, Berkshire, bought in 1966, when Page was 22. He knew “instinctively” it was the house for him. “I did a lot of sanding. I was putting up stud walls.” He shows me another picture, of him standing in the house, next to a jardinière he bought while on tour with the Yardbirds, “I was a bit of a collector [even back then]. I bought it in a flea market and it came back in the plane with me. That’s the room we recorded Whole Lotta Love in.” The thought of him with a jardinière on a plane… That’s unexpected, I say. “I know!” he laughs. “That’s why I showed it to you.”

Page had to sell the boathouse to buy this house. “It’s like guitars – in those days you had to trade in to go to the next one.” He was 28 when he bought the Tower House (he’s now 74) and he’s been looking after it ever since. It seems very young to take on a Grade I-listed house. Did he understand what was involved? “I knew what a Grade I-listed building was and what a privilege it was to live in something like this, yes.”

Tower House is sandwiched between two houses undergoing extensive building work (when we go into the garden later, the noise is deafening). Perhaps the most contentious of the two relates to the house belonging to the singer Robbie Williams. Williams wants to put in a basement complex which will come perilously close to Tower House. Page has appealed and the council has currently deferred a decision pending a tightening up of monitoring and supervision of works. At the moment, no one seems able to guarantee the building work next door won’t damage Tower House’s unique and irreplaceable interiors, which is of serious concern to Page.

That there is any debate that Tower House should be protected, is perplexing. The only other residential town house Burges built is Park House in Cardiff. It is also listed and has been described by CADW (Wales’s historic environment protector) as “perhaps the most important 19th-century house in Wales.” When a piece of Burges furniture recently came up for sale (there are very few) it was considered so imperative it didn’t go out of the country that the government placed a temporary export ban on it. The Higgins Bedford museum bought it. And yet, Tower House is full of Burges. In 2014, three English Heritage engineers, an EH inspector and a conservation officer visited Tower House and described its interiors as of “high heritage value… and highly vulnerable” and that there was no demonstration that the proposed works would “have no adverse impact”.

So protective is Page of the interiors and their sensitivity to vibrations, he only ever plays acoustic guitar in the house, doesn’t have parties there and has no television. Just before I go, Page says, a little sotto voce: “I’m sorry I couldn’t show you the kitchen. But…” he continues, leaning forward, “it’s got a La Cornue in it.” I am thinking which artist that is, and then I realise it’s a French range cooker. I see it as a small concession.

Later I talk to Matthew Williams, curator at Cardiff Castle and a world expert on Burges. How important is Tower House? “Oh very. Burges placed as much value on interiors as on the exteriors. Tower House is extraordinary… those amazing mosaic floors which any vibration could impact on. It’s one of the great hidden interiors of London. This house is coming from Burges’s own soul, his own heart. It’s pure, undiluted Burges. Someone [talking about the building works] needs to wake up and realise the importance of this building.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion