Campaign-Finance Reform Can Save the GOP

As the Republican Party tilts toward populism, its donor base is drying up.

If Republicans lose the House in 2018, expect the Trumpist right to start thinking very hard about the virtues of campaign-finance reform.

Late last year, as Republicans in Congress scrambled to pass a sweeping tax overhaul, there was a palpable sense that if they failed to do so, their most devoted financial supporters might revolt. One Republican, Representative Chris Collins of New York, told reporters, “my donors are basically saying, ‘Get it done or don’t ever call me again,’” a message that surely concentrated the mind. Just after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was signed into law, a number of major donors opened their wallets to GOP candidates, as if to positively reinforce good behavior, much as one might train a wayward child. Fears of a donor strike quickly receded.

Since then, however, the enthusiasm gap between donors on the left and the right has widened. Wealthy liberals remain highly energized by the prospect of giving Donald Trump a bloody nose in the coming midterm election. But many of their conservative counterparts have been notably restrained. Dozens of House Republicans are lagging behind their Democratic challengers in fundraising totals, a sure sign of vulnerability, and Democratic Senate incumbents in pro-Trump states are outraising their GOP opponents. Try as they might, leading Republicans have failed to drive home the urgency of their plight to their moneyed allies.

It could be that GOP candidates are simply not devoting enough time and energy to fundraising efforts. For example, Missouri Attorney General Josh Hawley, one of the party’s more impressive Senate candidates, has been accused of not pulling his weight when it comes to dialing for dollars, and he is not alone in this regard.

But consider the possibility that something else is going on—that what we are witnessing is the slow-motion dissolution of the always-awkward marriage between the GOP’s trade-friendly, tax-averse, and instinctively cosmopolitan major donors and its increasingly populist and nationalist voters. Recently, Rebecca Berg of CNN reported that while the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is widely seen as a bonanza for the wealthiest Americans, a number of prominent hedge-fund investors, all of whom have in the past donated generously to Republican candidates, have pulled back their support. According to Berg, they did so on the grounds that while the TCJA slashed taxes on corporations, its high-income rate reductions were comparatively modest, particularly when coupled with the law’s stringent cap on the state and local tax deduction. Indeed, many affluent residents of New York City, home to several of the donors in question, will see their federal tax liability increase in the wake of the TCJA. The clear implication is that self-interest is driving some major GOP donors to sit on the sidelines. Given that many of the donors identified by Berg are major philanthropists, I am skeptical. A more plausible interpretation, to my mind, is that many of them are troubled by what they see as the party’s populist and nationalist drift, and their objections to the TCJA have only confirmed their growing doubts about its direction.

Whether it is self-interest or ideological conviction that is the ultimate source of widespread donor displeasure, this apparent withdrawal of support raises serious questions for the president and his allies. Having exhausted the potential of tax cuts as a lure, certainly for now, how are they to finance a Republican Party that champions immigration restriction and economic nationalism, causes held in low regard by America’s upper strata? With the departure of Paul Ryan from the House, Republicans are losing a consummate diplomat, who understood the language of right-of-center hedge-fund investors, and who was broadly aligned with their more libertarian and cosmopolitan sensibilities. Assuming Republicans sustain heavy losses in 2018, the congressional GOP that remains will surely be less Ryan and more Trump, not to mention less donor-friendly. In a contest with a Democratic Party that commands supermajority support among the country’s affluent big-city professionals, a more blue-collar GOP anchored in the Deep South and the Rust Belt might well find itself consistently outgunned when it comes to raising money.

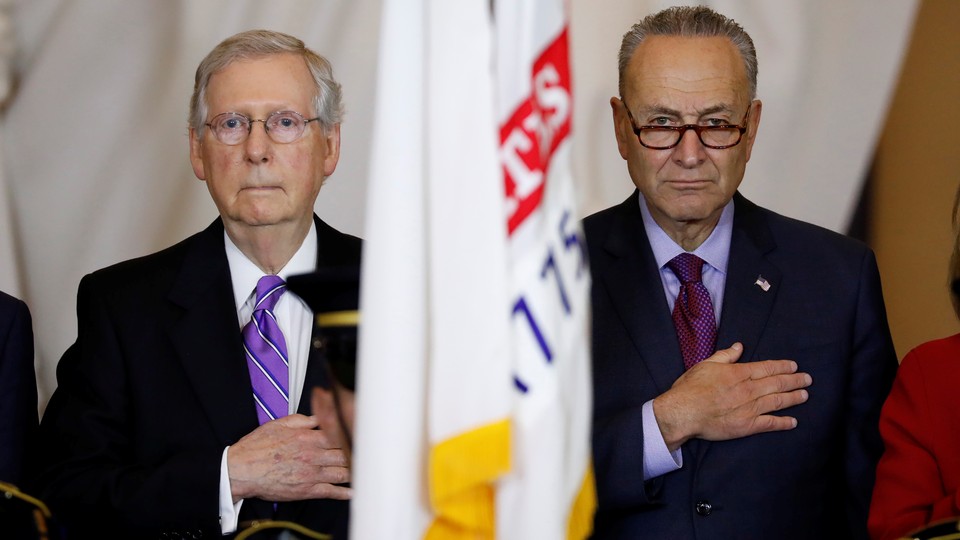

Enter campaign-finance reform. Traditionally, it is the Republican Party that has been most bitterly opposed to sweeping campaign-finance regulations or the public financing of campaigns. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, a prolific fundraiser himself, has long been a champion of a more laissez-faire approach. At the same time, it has been egalitarians on the left who’ve objected most strenuously to the campaign-finance status quo. However, the rise of Silicon Valley’s left-of-center tech elite is scrambling the picture. In a survey of the region’s successful technology entrepreneurs, David Broockman, Gregory Ferenstein, and Neil Malhotra found a blend of high-tax egalitarianism and open-borders cosmopolitanism very much at odds with the Trump-era GOP, and many have been willing to donate accordingly. More ominously, Republicans are losing ground with upper-middle-income voters, who are, in the aggregate, no less important than millionaires and billionaires when it comes to financing campaigns. As an imperfect proxy, 58 percent of college-educated voters are aligned with the Democratic Party while only 36 percent either identify with or lean towards the GOP, and the Democratic advantage is even more pronounced among voters with postgraduate degrees. College-educated suburban women have been a bulwark of the anti-Trump “resistance,” and a promising source of campaign donations for Democratic candidates. If it isn’t already the case that populist and nationalist candidates on the right find themselves at a disadvantage with wealthy donors, it will be soon. And that is why they ought to be eager for change.

One of the more striking facts about campaign fundraising in America is that candidates for Congress, and for many other offices, tend to raise more funds from people residing outside of their districts than from the people they are seeking to represent. The average House candidate in 2016 raised only 38.9 percent of all campaign funds in-district. In 2018, that proportion has fallen to 33 percent, though of course we still have many more months of fundraising to go. If you believe as I do that donating to a campaign is one of many ways for individuals to express their political beliefs, there is nothing intrinsically wrong about this state of affairs. After all, only 50 or so congressional districts are truly competitive this year, and that is more than most cycles. It stands to reason that motivated donors would lend their support to any candidates who can help them achieve their political goals, including those who seek to represent districts elsewhere in the country. Yet this reliance on wealthy out-of-district donors can have a distorting effect. For one, it disadvantages candidates who are out-of-step with such donors.

How might we address this bias? Take the “Seattle idea,” which draws heavily on the scholarly work of the liberal legal academics Bruce Ackerman and Ian Ayres. In 2015, Seattle voters approved a measure that provided all registered voters with a $100 “democracy voucher” they could then use to support local candidates of their choice. Among other things, such a system greatly expands the universe of potential donors, which in turn could influence the agendas and sensibilities of aspiring elected officials. Representative Ro Khanna of California, an iconoclastic Democrat, has proposed a similar system for funding federal campaigns, in which voters would be issued $50 in “democracy dollars.” Under this system, candidates would be more than welcome to raise campaign funds exactly as they do today. But they would have the option to instead enroll in the democracy dollar system, in which case they would be barred from raising hard-money contributions.

Imagine adding a civic-republican twist to Khanna’s proposal: What if voters could only use their democracy dollars to support candidates for whom they could actually vote? That would further encourage candidates to heed their constituents. We would thus have candidates running on two separate tracks: those who would rely solely on their ability to garner contributions from the women and men they are seeking to represent, and another for those confident in their ability to raise campaign funds from wealthy out-of-state donors. There are, to be sure, kinks to be ironed out. Inevitably, unscrupulous grifters will seek to hoover up democracy dollars for their own purposes, which will necessitate strict regulation. And yes, that is less than ideal. But without something like Khanna’s system, Republicans might have no choice other than relying on an endless series of celebrities and provocateurs who, like Trump himself, can attract endless hours of free media attention. That wouldn’t be so wholesome either.

Campaign-finance reform has no purchase in a Republican Party led by Paul Ryan and McConnell. Once they leave the scene, however, it might strike populists and nationalists as indispensable.