Anxiety can come in many forms: from feeling nervous about giving a presentation, to not wanting to leave the house. But can an arts festival provide some sort of balm for mental health problems?

An ambitious and large scale project, The Big Anxiety festival – a University of New South Wales initiative run over seven weeks in Sydney – is trying to not only get people talking about their mental health, but also to alleviate some of the associated pain.

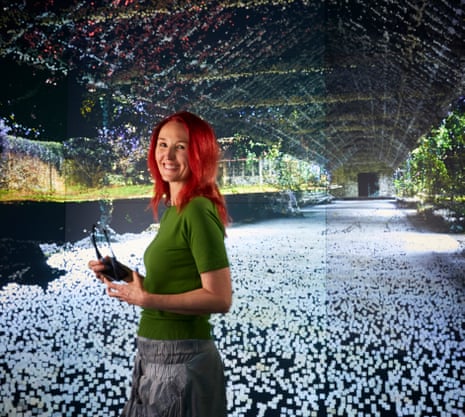

The festival is the brainchild of Prof Jill Bennett. “There’s a lot of evidence that art has a lot of impact when it comes to mental health. It’s not just a diversion – there is evidence that it impacts on mood and wellbeing,” she says.

This connection is “something that we don’t tend to exploit – so we wanted to create something new in the cultural landscape”.

The biggest mental health and arts festival in the world, it features artists and scientists from around Australia and internationally, staging more than 60 events. These include relaxing art installations, to talks, to an event called “Awkward Conversations” with an “emphasis on participation and people. It’s very bespoke one-on-one, relaxed conversations about mental health.”

So why a festival?

“We live in anxious time,” says Bennett. “Mental health is the one area of health where there are no cures. Some things work a little bit, but not completely. But maybe the arts can be part of the mix. There are very few areas of medicine where you could say that. But we haven’t really systematically explored the effects of arts on mental health.”

With input from the Black Dog Institute, the festival will have a “strong emphasis on conversation and engagement”.

“We want to develop a new kind of festival that is evidence based, which also crosses over into the health sector and will create new opportunities for artists. If we can change the landscape by creating a new festival, it could enable the arts to be more practical.”

An example of some of projects showing at the festival include Parra Girls Past and Present, where a 3D cinema work and self-guided audio walk evokes the site of abuse at the Parramatta Girls Home. Up until the early 1980s “children at risk” were held at the home, and subjected to abuse.

Returning after 40 years, the Parragirls – together with media artists – have created a work immersing viewers in the sights and sounds of that time and place.

“This work is about telling their story and owning it,” Bennet says. “It’s an amazing immersive project. We need to tell story, as it’s an important part of the history of state and nation.” But it’s also therapeutic. “These women did not have the level of psychiatric and social support they needed, and this project is part of addressing that.”

Sydney visual artist Abdul Abdullah is also taking part in the festival – and says he relates to the experience of anxiety. “I was really excited about being a part of the festival. Anxiety has played a part in my own life and the life of people close to me.”

“We [in the Muslim community] are all affected,” he says, describing “a siege mentality” that’s affected Muslim communities in Australia.

“There are symptoms of a shared mutual sense of anxiety about where we sit, and the symptoms are of dysfunctional behaviour in our communities – feeling vilified, alienated and isolated.”

Abdullah’s own work “is about the criminality associated with the Muslim identity,” he says. “It’s a combination of [factors]: it’s going to an airport and being singled out; it’s in 2015, where 200 houses [were] raided by Asio with only one arrest. Those types of things.”

As for the title of the festival, Bennett says it was chosen “because it’s very inclusive. Almost everyone knows what anxiety is to some degree. We didn’t want to label it as a ‘festival of mental health’ – so that’s what really powerful about it. Sixty-five per cent of Australians with a mental health problem don’t get help. What art does is to provide the rich forms of engagement and thoughtful communication.

“Mental health campaigns aren’t stimulating and fun. We are offering something enjoyable to do on a Saturday afternoon.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion