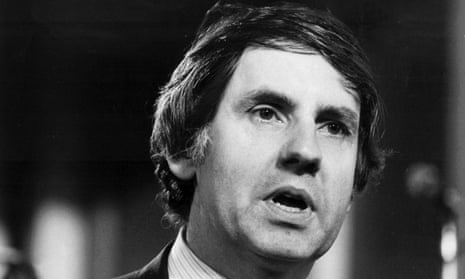

The former Treasury minister Denzil Davies, who has died aged 80, was a brilliant but mercurial politician for whom the promise of a glittering Westminster career was thwarted by the unfortunate combination of Labour’s long years in opposition after 1979 and his somewhat volatile character.

He famously brought an end to his own political prospects by resigning the shadow defence portfolio in a 2am telephone call to the Press Association in 1988. His remaining 17 years in the House of Commons were spent largely in obscurity on the backbenches.

The son of a colliery blacksmith from Carmarthenshire, Davies left the valleys of south-west Wales for Pembroke College, Oxford, where his outstanding intellect was confirmed by a first-class honours degree in law. Elected as Labour MP for Llanelli in 1970, he was appointed to the Treasury by Harold Wilson in 1975, leapfrogging the junior ministerial ranks to enter the government directly as a minister of state. He was the youngest member of the privy council when he was sworn a member in 1978 and was identified as a possible future Labour leader by the then chancellor of the exchequer, Denis Healey.

Davies was a charming, popular and convivial man who throughout his 35 years in the Commons resisted aligning himself with the factions of either left or right in the Labour party and was driven, rather, by his own strongly held political convictions. He opposed devolution to Wales, campaigned relentlessly against Britain’s membership of what was then the European Economic Community and, while opposing nuclear weapons, rejected unilateral nuclear disarmament for the UK in favour of a conventional defence strategy within Nato.

He had been shadow defence secretary for five years when his frustration erupted after a long summer’s evening on the Commons terrace and he resigned by telephoning the PA’s political editor, Chris Moncrieff.

He blamed Neil Kinnock’s repeated failure to consult him before announcing changes in defence policy but, in reality, in any case had a difficult relationship with the then party leader. He had tried to resist Kinnock reappointing him to defence after the general election in 1987 – having unsuccessfully sought instead to become foreign affairs spokesman – and was irritated by Kinnock’s style of leadership.

It was because of this that he chose to resign in the middle of the night, a plan of action he plotted in advance and discussed with his close friend and Welsh parliamentary colleague Ted Rowlands.

Davies believed that if he chose a more conventional manner of resignation, Kinnock would use his staff to rubbish his arguments and reputation; some justification for which was provided by the erroneous suggestion, which was widely put about during the subsequent public row, that Davies had acted because he had spent too long in the bar. Moncrieff has confirmed that it was evident during their phone call that Davies knew exactly what he was doing.

He was a man whose politics had been formed and burnished by the hardships of the society in which he was raised. He was born into a chapel-going family in Cynwyl Elfed and educated at Queen Elizabeth grammar school, Carmarthen. His father, Gareth, a trade union activist who had been blinded in an industrial accident, encouraged his son’s pursuit of education, and this led him also into early membership of the Labour party, which he joined as a teenager.

At Pembroke College, Davies was spoken of as the best student of his year. He became a Francis Bacon scholar at Gray’s Inn, again securing a first. After graduating, he lectured in law at the University of Chicago for a year in 1963 and then at the University of Leeds in 1964. He was called to the bar at Gray’s Inn in 1964 and practised as a lawyer, specialising in tax and personal injuries, until 1975.

He had been selected in 1969 to follow Jim Griffiths, the first secretary of state for Wales, as MP for Llanelli, a rock-solid safe Labour seat for which he was elected the following year. He was a powerful public speaker and in his maiden speech described the century of filthy, black and dusty environmental pollution his countrymen had suffered in the pursuit of industry. “Pollution was and still is in the main the consequence of man’s greed,” he told the Commons in a contribution commended for its conviction.

Davies was a diligent constituency MP and one early success was helping resist the installation of a military gunnery range at Pembrey on the Carmarthen coast, which was instead turned into a country park.

At Westminster he became parliamentary private secretary to the Welsh secretary John Morris in 1974, until becoming a minister himself in 1975. He remained a Treasury spokesman in opposition after Margaret Thatcher took office and then in 1981 was appointed by Michael Foot as a foreign affairs spokesman with particular responsibility for Europe. He was switched to defence in 1982 and briefly to Welsh affairs when Kinnock first took over as leader in 1983, before then being moved back to defence and disarmament.

Davies had stood against Roy Hattersley for the post of deputy leader in the party’s leadership elections that year. He came third with a derisory 3.5% of the vote but his popularity among Labour MPs was nevertheless shown by his success in repeatedly standing for election to the shadow cabinet without being a member of any factional “slate” or, indeed, having any campaign organisation. In 1986 he reached third place.

On the backbenches Davies won a reputation for being very much his own man and despite his lifelong commitment to his party, he often made clear his lack of respect for either Kinnock or Tony Blair as leader. In doing so, however, he thus guaranteed his place as a backbencher during the Blair government. He stood down as MP in 2005.

The author of several legal text books, in retirement Davies published The Galilean and the Goose (2010), the product of five years’ research relating the history of Christianity to the fall of the Roman empire.

The compensation of his latter years was to have found profound happiness in his second marriage, in 1989, to Ann Carlton, the journalist and author, who had previously worked as a member of the Labour party research staff. His first marriage, in 1963, to Mary Ann Finlay, ended in divorce in 1988.

He is survived by Ann and by the children of his first marriage, Jane and Steven.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion