For a band of ardent fans, the television and radio satirist Chris Morris has been elevated to the status of an oracle. The brand of surreal satire he trademarked on his controversial Channel 4 show Brass Eye, involving pastiche news stories that hysterically chronicled, for example, the pseudo-discovery of heavy electricity plaguing Sri Lanka like “a ton of invisible lead soup” now seems to have preempted fake news 20 years ahead of its time.

This week many of his followers will be meeting up in a spirit of celebration. Proud, and filled with subversive glee, they will line up on Thursday evening for the latest of a series of secretive 20th anniversary events, some no doubt muttering about “Shatner’s Bassoon”.

In honour of the Brass Eye birthday there have been tributes published and repeats scheduled, but the surprise popularity of an almost unpublicised touring event, called Oxide Ghosts: The Brass Eye Tapes, perhaps says even more about the enduring influence of the show. Billed as “part documentary, part artwork”, Oxide Ghosts has been quietly selling out in independent cinemas across the land.

“It really shows the power of a niche enthusiasm,” said the playwright Jonathan Maitland, who has chaired the discussions at two of these events. “All the shows so far were sold out. It is almost a cult. It reminds me of the way fans of Morrissey keep on carrying the flame.”

The evening takes the form of previously unseen out-takes from the original television show, put together carefully by Brass Eye’s director Michael Cumming, followed by a question-and-answer session.

“The audience absolutely love it,” said Maitland. “As far as I could see, there were a lot of bearded men in their middle age there, many asking very detailed questions about their favourite episodes. They were a very media-literate crowd.”

Although Morris has given the event his full approval at a distance, he was not actively involved in its creation. The satirist, who is known to be publicity-shy, described Oxide Ghosts to the Observer as Cumming’s “impressionistic account of his experience”. And even Cumming himself is reticent about saying anything to promote the screenings. The live event, he told the Observer, explains everything he wants to say.

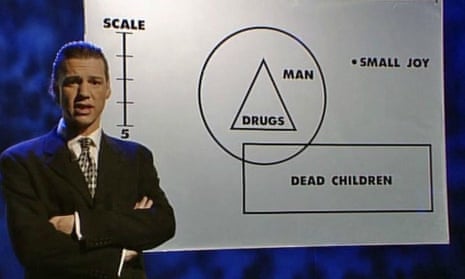

Such self-effacement creates a sense of mystery which is, of course, savoured by the fans. Those who can recite each word of, say, the spoof report about an epidemic addiction to a made-up drug called Cake, also revel in the recondite nature of the knowledge they share.

The first Oxide Ghosts event took place this May in Manchester, and the show has since gone on to play at venues in Bristol and Liverpool. An extra show at the Curzon in London has just been added following public demand, and its nationwide tour continues until the end of November.

For those who did not watch Brass Eye, the episodes each revolved around a themed series of stunts and fake news stories. It was the kind of comic fare more familiar to viewers now, but it has rarely benefited from such poker-faced delivery, or such acid intent. Morris’s target was often the news media, or at least the sensationalist, macho tics of news coverage, whether from the lips of one of his ludicrous fictional reporters Ted Maul or Austen Tasseltine, or from a series of grave presenters, variously titled David Jatt or David Unesco.

Celebrities and politicians were ridiculed for the alacrity with which they jumped on a media bandwagon. Want to speak out against the appalling abuse of an elephant in a German zoo who has been left with its trunk stuck in its fundament? Step up Paul Daniels and Britt Ekland. (Cumming revealed in one Oxide Ghosts Q&A session that Toyah Wilcox was the only celebrity approached by the Brass Eye team who actually turned down the chance to denounce this unlikely outrage.)

As Maitland admits, viewed today, some of the pranking does look unnecessarily cruel. A few of Morris’s celebrity “marks”, such as the DJ Bruno Brookes or the late agony aunt and health campaigner Claire Rayner, seem innocuous now. On the other hand, Rolf Harris and Donald Trump also made fleeting appearances. And gratuitous cruelty was always part of the point. Let’s not be moderate, Morris seemed to urge.

His attitude came with a track record. Channel 4 must have had a clue who it had hired. Morris had “previous” long before his relatively mild BBC2 spoof news show The Day Today introduced the self-regarding sports reporter Alan Partridge to the British public. As a DJ on BBC Radio Bristol in 1990, he had been fired for filling a newsroom with helium during a broadcast.

The reaction of tabloid newspapers to Brass Eye was incendiary. They feasted on a succession of the show’s affronts to decency and, eventually, the then Channel 4 chief executive Michael Grade intervened to demand cuts. In the last show, Morris retaliated with a very rude subliminal message.

Understandably then, a key element of the appeal of the show for its veteran fans is the suspicion that a programme like this could no longer be made. Heightened regulatory restraints would now stop many of the naughtier Brass Eye expeditions in their tracks.

Even back in 1997, it was a bit touch and go. Writing this summer, Cumming said: “Brass Eye very nearly never went to air at all. It was deemed unbroadcastable on more than several occasions. Material was cut for numerous reasons, some legal, some editorial and some simply because we didn’t have room to fit it all in.”

All this meant there were plenty of offcuts to choose from when Cumming came to compile Oxide Ghosts. Wading through hours of unseen material in a personal archive of VHS “rush tapes” built up over two years of directing the pilot shows and the series, he selected the best unseen material. These include a scene in which a giggling Morris has his own “John Noakes moment” with an elephant, although characteristically Morris’s encounter is far more extreme.

Cumming, a graduate of the Royal College of Art Film School with a back catalogue of acclaimed television comedy behind him, is now best known for making Matt Berry’s show Toast of London. Earlier this summer, he explained why he has always turned down interviews about Brass Eye. “The shows were surrounded by secrecy and I saw no reason to shatter any myths,” he wrote.

Yet, when the 20th anniversary loomed, he made a first cut of Oxide Ghosts and “nervously” showed it to Morris. “There was a fairly good chance he might not want the material to be seen or, at best, have a very long list of cuts he wanted made. As it turned out, he was brilliantly supportive and was happy for it to be seen exactly as it was.”

The duo agreed the new film should not be available online or shown on television. “We loved the idea that in this world of instant gratification, where everything is available at a click, you would have to actually go to a screening to see it,” Cumming wrote.

When the original series ended, the novelist Will Self declared in the Observer that Morris “might possibly be God”. Such a thing would explain, Self said, why the world is so absurd and so unfair.

For Maitland, the series remains testament to the power of stepping out of the entertainment comfort zone. “It was comedy, Jim, but not as we know it, because there was a strong moral force behind it,” he said. “Morris could have been an incredible journalist, but he saw that television news had been begging to be parodied. Brass Eye has been copied, but it can never be the same, because Morris is not really a comedian in the usual sense.”

When the Oxide Ghost audiences line up, Cumming has admitted taking satisfaction from the evidence that some television shows “last a bit longer than the week of transmission”.

“To celebrate the 20th anniversary of Brass Eye and find that there is still an audience who remember it so fondly, is gratifying but not totally unexpected,” he said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion