Republicans Are Throwing Away Their Shot at Tax Reform

There’s a manifest need to lower corporate tax rates—but instead of building consensus, the GOP is pursuing a bill that’s likely to be rolled back even if it passes.

America badly needs corporate tax reform.

The United States pretends to tax corporations heavily. But those heavy tax rates are perforated by randomly generous rules such that many tax-efficient firms pay nothing at all, or even receive money back from the U.S. Treasury. The result is heavy unfairness between industries and firms, an unfairness that many economists believe systematically distorts investment decisions. U.S. productivity growth has been sluggish since the Great Recession—and had actually turned negative by the beginning of 2016.

At the same time, the corporate share of the federal-tax burden has dwindled over the years and decades. More and more of the cost of government now falls upon the payroll tax, which weighs most heavily on low- and middle-income wage earners. These Americans are suffering stagnating incomes, very probably because of the poor productivity growth of the past half-decade.

Lowering the corporate rate while tightening collection—with a view to raising more revenue in a more rational way—has been a good government cause since the late 1980s. John Kerry campaigned on it during his presidential run, in 2004, as NBC News reported at the time:

“Some may be surprised to hear a Democrat calling for lower corporate tax rates,” Kerry told an audience at Wayne State University [in Michigan]. “The fact is, I don’t care about the old debates. I care about getting the job done and creating jobs here in the United States of America.”

Now, in 2017, the all-Republican federal government at last has a chance to make progress on this goal. And it is throwing that opportunity away.

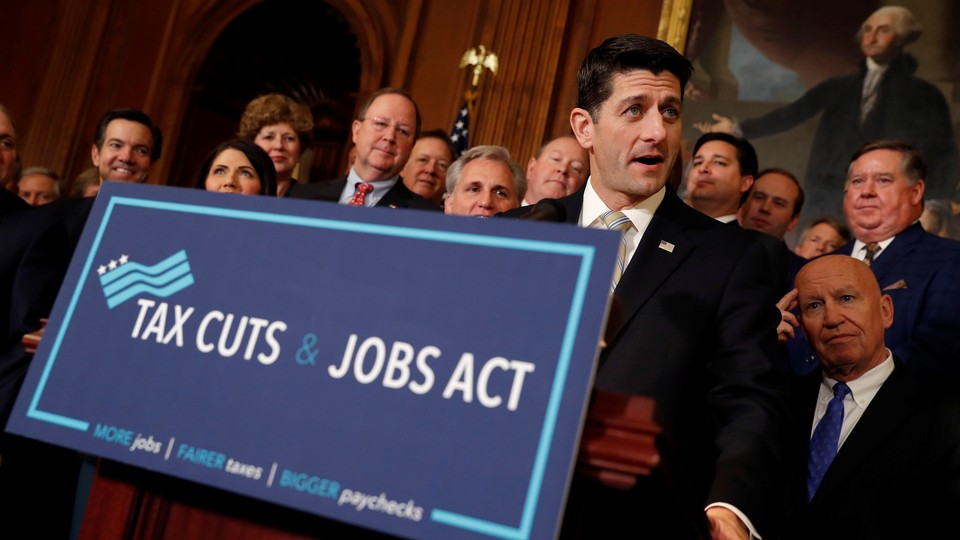

As I write on November 19, it may seem like the GOP tax plans are carrying all before them. A big tax cut has passed the House. A somewhat different plan passed late Thursday night through the Senate Finance Committee. The president is bellowing on Twitter his readiness to sign almost anything that arrives on his desk.

But what is heading toward him is not the kind of reform that can command broad political support, and thus stand the test of possible electoral defeat in 2018 and 2020. It’s a scandalous expression of upper-class and Sunbelt chauvinism that will melt away within weeks of the next Democratic electoral success. Even if the plan becomes law, as still seems improbable in the face of its terrible poll numbers, what firm would venture a long-term investment based on tax changes so likely unsustainable?

Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s old rule of thumb for bills before the Senate—“They pass 70–30, or they fail”—no longer applies. Seventy-vote majorities no longer exist in this hyperpartisan era. The Affordable Care Act passed with only 60 votes. But the spirit of the rule lingers. By refusing to hold hearings and forestalling Congressional Budget Office scoring, Republicans have moved fast. But they have not convinced the public mind to recycle an antique but still meaningful phrase. They may win a vote. They have not won the argument. What they are doing will not last, and will therefore not deliver any of the promised benefits. Their strategy is the equivalent of a 1980s-style corporate raid, which will yield a hasty and morally dubious windfall for a few insiders while damaging the longer-term economic health of the larger enterprise.

Corporate tax reform is an argument that conservatives and Republicans could and should win. Among the advanced economies, only France—at 34.41 percent—imposes rates even close to the statutory U.S. rate, which including state-level taxes averages 38.91 percent. Nations that are members of the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation, by the same metric, average 24.18 percent; European states, 18.35 percent.

Of course, only the worst-managed or unluckiest American companies actually pay that 38.91 percent. In the 1950s, a third of federal revenues were derived from the corporate income tax. In the mid-1960s, the corporate tax still yielded more revenue than the payroll tax. But since then, revenue collections from the corporate tax have tumbled steeply relative to other tax sources. Today the federal government collects only about 10 percent from the corporate income tax. The payroll tax contributes almost three times as much.

In the 1960s, the ratio of federal collections between individual and corporate income taxes was about 2 to 1. Since the Great Recession and the lapse of the Bush tax cuts, this ratio has approximated 5 to 1.

The paradox of high rates and low yields is explained by the rational lobbying strategy of corporate firms. Business in general would benefit from lower rates. But from the perspective of any individual firm, the highest return on lobbying investment is earned by seeking special favors of value to that particular company or industry. A decade-long effort to reform corporate taxation might reduce the nominal rate to 25 percent. A shrewdly negotiated special favor can cut a company’s tax obligation to zero overnight.

From the point of view of future U.S. growth and prosperity, the broad outline of tax reform seems obvious. Lower corporate rates to somewhere between 25 and 30 percent, the developed-world norm. Tighten collection so that the rate is actually paid. This is one reform that should come near to paying for itself, since collections from the present loopholed system have shrunk to such relatively low levels. Make up any difference by raising other, underperforming taxes, especially excise taxes; while collections from the individual income tax have doubled since 1997, receipts from the federal excise tax on alcohol have risen only by one-third over the same period.

Those are changes that could command broad assent. The present Republican plan to use the manifest need for corporate tax reform to shift the burden of the individual income tax from the wealthiest to middle-income families in blue states will not.

Congressional Republicans well appreciate the unpopularity of what they are doing. That’s why they are short-circuiting the traditional legislative process, bypassing hearings and other opportunities for public comment. The more the public knows, the more jeopardized their plan becomes. Since the Great Recession, the GOP has grown both more extreme in its goals and more radical in its methods. Apocalyptically pessimistic in its view of America’s future, it seems determined to seize for its donors and core constituencies as much as it can, as fast as it can, as ruthlessly as it can. It will then take advantage of the U.S. political system’s notorious antimajoritarian bias in favor of the status quo to defend the grab over the coming years and decades. Repeal and replace failed. The new slogan is: Rush, grab, entrench, and defend.

Despair is always a bad counselor. This hubris and haste will not deliver the results that U.S. businesses want and that the American public should expect. A normal Republican president would say so. A normal Republican president would enlarge the narrow views of his congressional party—if only to win a second term for himself, but ideally because presidents by their job definition are compelled to think of the wider interests of the nation. But President Trump, elevated by the Electoral College on the basis of a Michael Dukakis–size share of the popular vote, is not only the least public-spirited president in U.S. history, but also the most ignorant and shortsighted. He struck an implicit deal with the congressional Republicans during the campaign of 2016: If they would shield his wrongdoing, he would sign their bills. It’s the one of the rare commitments in his lifetime on which he has not (yet) reneged.

An opportunity to achieve a sensible improvement by broad consensus is being flung away in favor of accumulating special favors for “special” people. If it succeeds, it will not last. And it probably will not succeed. The differences between the House and the Senate are real; settling them will take time.

Some Republicans may reason, as Paul Krugman tweeted on Thursday, “You might think that growing evidence that 2018 will be a Dem wave would make some Rs break ranks. But here’s the thing: Probably many of those Rs figure that they’ll be wiped out regardless … So if you’re, say, a GOP Congressman from a well-educated, affluent CA district, you might look at VA results and say, ‘Well, by 2019 I’ll be outta here and working as a lobbyist on K Street.’ So keeping the big money happy is what matters.” Not all will think thus, however, and certainly not all will arrive at Krugman’s conclusion equally fast. Vestigial instincts of self-preservation among Republican members of Congress will slow the legislative timetable against the unforgiving clock. It’s very possible, too, that in the face of negative polling, Trump may panic and go back on it, sabotaging the entire project. It’s quite possible that the only legacy of the great tax reform push of 2017 will be raw material for devastating Democratic attack ads in 2018.

It didn’t have to be this way. It should not be this way.

A rationally conservative party of business and enterprise could, and should, have written a corporate tax-reform bill that is compelling on the merits. The slowdown of U.S. productivity growth would be the country’s leading problem if U.S. constitutional democracy were not being attacked from the White House at the same time. The GOP submitted to Trump in 2016 very largely to reach this moment. The ironic outcome is that his success that year doomed the very prize for which his party sold its soul.