Toronto Airport’s Inunnguat Are Sending the Wrong Message

New attention from the Inuit community reveals that these statues signify “a bad omen.”

If you fly into the Toronto Pearson International Airport via Terminal One, you’re welcomed into the city by three human-like figures, made out of stones placed on top of stones. One has its arms straight out, one has them raised, and one is making them into a sort of “L” shape.

To some travelers, the sculptures may resemble a trio of aircraft marshallers* (or, as someone said on Facebook, a few friends trying to hail a cab). But to those in the know, they’re bearing a much more dire—and almost certainly unintended—message. These are inunnguat, traditional Inuit artworks that encode particular messages. And an inunnguaq with its arms raised up means, essentially, “Stay away! This is a place of violent death.”

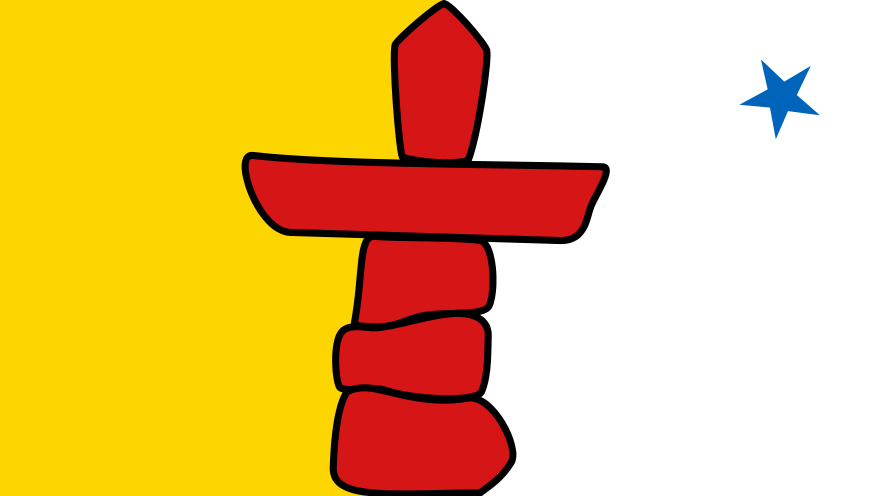

If you’re looking to add some Inuit artworks to your airport, building some inunnguat isn’t a bad idea. Along with inuksuit**—sculptures that, while also made of stone, take less humanoid forms—they are traditionally constructed as navigational and land-reading aids, meant to indicate good fishing spots, sacred areas, or places of danger. Because of this, they’ve become a symbol of Inuit culture itself: for example, there’s an inukshuk on the flag of Nunavut.

Over the years, though, their usage has broadened, and now they are sometimes employed to represent Canada as a whole. Such a broadening can lead to a loss of the specific meanings that made the symbol important in the first place, something that many Inuit people have pushed back against. When Vancouver hosted the Winter Olympics in 2010, the Olympic Committee chose an emblem that resembled an inunnguaq, prompting backlash from several First Nations leaders. (It didn’t help that they called it an inukshuk.)

A similar loss of nuance was probably responsible for these airport sculptures. As the CBC reports, the federal government commissioned these particular artworks back in 1963, from an Inuk artist named Kiakshuk. Save for a brief stint in storage, they’ve been standing near Terminal One since then, in these same positions. The concern about them is new, and was spurred when CBC Nunavut posted photos of the statues on Facebook, prompting a near-immediate response from Inuk readers. (“That kind of inukkuk/inuksuk signifies a bad [omen], a place of horrible death,” one, Jessie Kaludjak, wrote.)

It’s unlikely that Kiakshuk was trying to send a morbid message. So what happened? One possible answer comes from elder Egeesiak Peter, who helped Kiakshuk with the statues when he was a young man. Peter, who is now in his 80s, told the CBC that the original vision for the art differed greatly from what is now on display.

Kiakshuk, he explained, chose and shaped the stones to make one giant inunnguaq, and numbered them to aid in its reconstruction. Somehow, after it was shipped to the airport and rebuilt, it became three smaller ones instead, with raised arms.

Have you seen our Inukshuk? Built with rocks from Nunavut thanks to @FirstAir #NationalAviationDay #airportthrowdown pic.twitter.com/rxo9JxRthI

— Ottawa Airport (@FlyYOW) February 23, 2016

The airport told the CBC that they are working with Piita Irniq, an Inuk artist and former political representative, to “improve the presentation of the artwork.”

Irniq has some very specific credentials: he designed and built the Ottawa airport’s inukshuk, which is more pyramid-shaped, with a hole in the middle. Traditionally, this type of structure led people in the direction of good hunting and fishing areas—you could look through the peephole and see which way to go.

“[Irniq] said he believes this traditional meaning makes sense for an airport,” the CBC writes. It’s certainly better than telling everyone your airport is a death trap.

*Correction: This post previously stated that the inunnguat might resemble air traffic controllers. The correct reference is to aircraft marshallers.

**While the CBC refers to the airport sculptures as inuksuit, we are calling them inunnguat, in accordance with Irniq’s differentiation.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook