Sailors’ Valentines Were Painstakingly Crafted, But Not by Sailors

They made great last-minute gifts after months at sea.

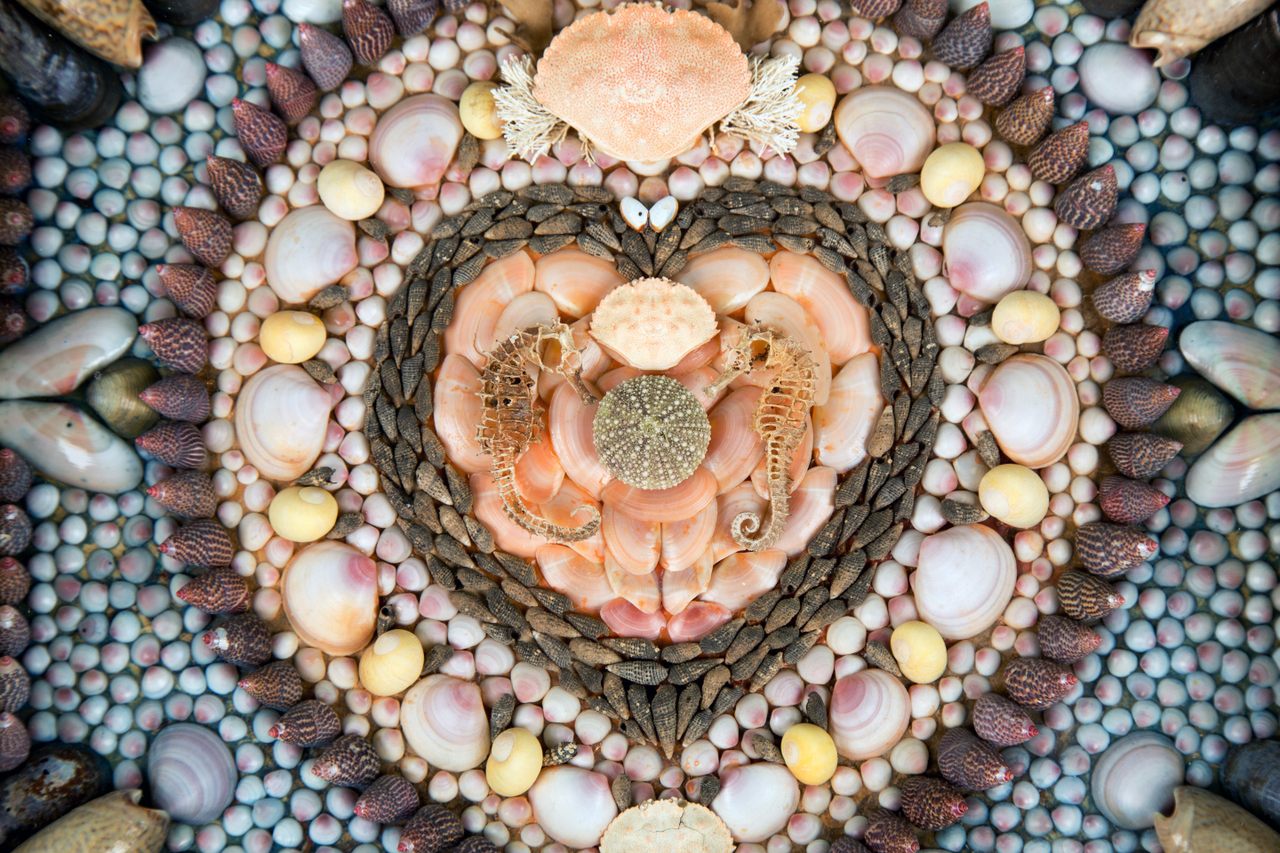

Beaches and shorelines around the world are scattered with all manner of art supplies, from cockle to clam and conch shells. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, seashells like these were intricately arranged into geometric mosaics known as “sailors’ valentines.” They were—and still are—made by gluing hundreds of shells onto cotton batting, and framing the work with octagonal cases of wood and glass. Either as single panels or hinged pairs, they’re usually no larger than 18 inches across, and less than two inches deep. The designs incorporated hearts, flowers, and nautical symbols such as anchors or compass roses. They might also bear a message—“Home Again” or “Forget Me Not”—spelled out in tiny shells. They were given by whalers and merchant seamen to loved ones when the men safely returned home from what could have been months or even years at sea.

For many decades it was thought—rather romantically—that the sailors themselves had made these mementos, when their ships were stuck in the doldrums or during shore leave, from shells they collected with their own tattooed hands, on beaches halfway around the world. They were considered maritime crafts, like scrimshaw—scenes etched with sail needles on whale teeth and other forms of marine ivory. The valentines’ popularity was fed by the Victorian shell collection craze known as “conchylomania” (a relative of “tulipmania”), which filled curiosity cabinets across England, the Netherlands, and the United States with as many unusual specimens as one could find or purchase. Ladies also worked on shellcraft beside their needlecraft.

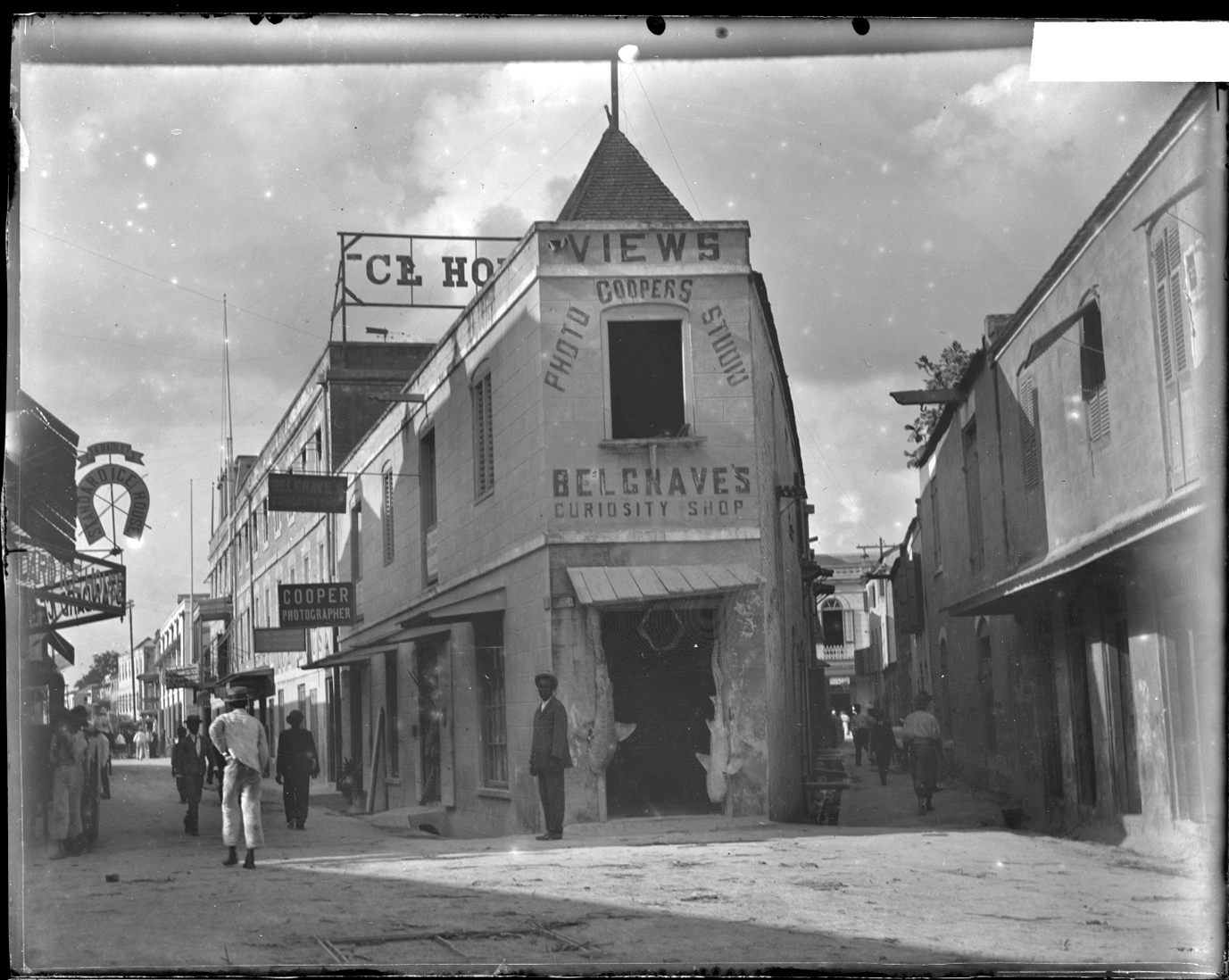

It wasn’t until the publication of a February 1961 article in the magazine Antiques, by Judith Coolidge Hughes, that the myth of the lonely, artistic sailor began to come undone. Hughes discovered that a woman restoring an antique sailor’s valentine in a Massachusetts collection found an early 1800s clipping from the newspaper The Barbadian in the backing. The clipping mentioned that these “fancy work” items were for sale at Belgrave’s Curiosity Shop in Bridgetown, Barbados. Another clue to their true origin was that most antique examples incorporate similar designs and are created from similar shells, mainly from the West Indies, including Barbados keyhole limpets, janthinas, and King Venus clams. And as early as 1750, in his A Natural History of Barbados, English missionary Reverend Griffith Hughes wrote about women on the island creating beautiful designs from seashells: “With what truly romantic ideas must it inspire one, to sit in a room furnished with riches of the most distant shores and oceans!”

It’s now believed that the curiosity shop’s owner, Benjamin Hinds Belgrave, organized women on the island into a cottage industry to produce the valentines for sale. Barbados was a frequent port of call for North Atlantic–based ships, often the very last stop before home. While provisions were gathered for the last leg of a journey and vessel repairs were made, sailors naturally strolled the streets and shopped for souvenirs to give to loved ones. So the valentines were less labors of love and more like last-minute purchases at airport gift shops. But their beauty and craftsmanship endure, and so does the tradition.

Whether 19th-century original or contemporary descendant, a sailor’s valentine is all about painstaking perfection. Pamela Boynton, an award-winning valentine artist and author of Contemporary Sailor’s Valentines: Romance Revisited, designs and produces hers using traditional techniques, including creating a template, gluing a colorful array of shells onto cotton batting, and encasing the delicate display in octagonal boxes (a requirement for the artistic competitions she competes in). Little in the conceptualization and construction processes has changed in nearly 200 years, but some artists now rely on more modern materials. Synthetic adhesives, acid-free mounting board, and birdseye maple may take the place of the hide glue, cotton batting, and Spanish cedar or mahogany most often used in Victorian times.

While the size (but not the shape) of the boxes varies, an artist needs on average dozens of different types of shells, and at least a couple hundred of each, to make a substantial design. Boynton, a resident of Sanibel Island, Florida (home of the Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum), uses both shells she collects locally and those she imports for specific colors—primarily from the Philippines—including green and white tusk shells and colorful urchin spines. The “brick and mortar” shells commonly used to make up the bulk of the designs include apple blossoms, rosecups, white nassa, and green limpets. Sometimes fish scales, seaweed, seeds, or seahorse bones make their way in as well.

A typical valentine takes hundreds of hours to complete, but as the fitting and gluing process proceeds, the puzzle solving can become meditative. It probably would have been a nice way to pass the hours on a long sea voyage.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook