The Tragic Side of Tide Pods

Bella Mancillas is standing on her head.

For an 8-year-old to be exuberantly goofing off, performing cartwheels and splits while grownups are talking, is nothing out of the ordinary. But as her mother, Katie Mancillas, is explaining, in Bella’s case, it’s almost miraculous.

Six years ago, when Bella was 2, she was rushed to the hospital because she was vomiting so uncontrollably that she inhaled fluid into her lungs, blocking her airways. Not long after she arrived, Bella stopped breathing and briefly flatlined. “Oh, my God, I think Bella’s gonna die,” Katie remembers telling her sister.

The cause of Bella’s near-death experience wasn’t a nasty stomach virus or a toxic pesticide. According to Katie, it was a squishy, multicolored packet that’s an increasingly common presence in American homes: a Tide Pod.

Katie Mancillas often did the laundry for her large family in the suburbs of San Diego, lugging loads to the nearby laundromat. When she first saw the pods—easily portable packets of concentrated detergent, then new to the market—she thought they’d be a useful convenience.

On Nov. 17, 2012, Katie brought home her first case of Tide Pods, from Costco, and placed them on the kitchen counter. Katie recalls that the case was clear plastic, with a button on top that opened the lid when pushed. She was unloading her groceries, she says, when she turned around to see that Bella had opened the case and was about to put a pod in her mouth. She bit into it before Katie could snatch it away. “It literally did look like candy. And I honestly think that that’s what she thought it was,” says Katie.

Katie immediately called poison control and was told to force Bella to drink 32 ounces of water and wait 30 minutes to see if she started vomiting bubbles. “At 27 minutes, she started projectile vomiting,” Katie recalls. “It was just bubbles, like from a bubble machine.”

They raced to the hospital. When they arrived, Katie saw Bella turn blue as medical staff struggled to steer a breathing tube through the bubbles in her throat. After Bella was intubated, they transferred her to a children’s hospital, where she was placed into a medically induced coma so that they could try to suction the detergent out of her lungs.

As Katie retells the story, Bella ends her impromptu gymnastics routine and nestles into her mother’s side on the couch. Her otherwise bright demeanor—illustrated by the glitter that covers her T-shirt, backpack, and notebook—turns somber.

After two weeks of Katie not knowing whether her daughter would pull through, Bella started breathing on her own again. But she had serious challenges ahead. She had to relearn how to walk and talk. She got sick often after the episode, which her doctor surmised was because of the lung injuries she had sustained. The most serious effects have been on her eyes. Bella has a type of strabismus in which the eyes are misaligned vertically; her doctors attribute it to oxygen deprivation during the incident. She has struggled to read and write properly, and she’s had two eye surgeries, with a possible third to come.

“It’s hard,” says Bella, who in this moment sounds more like a jaded adult than a carefree kid. “But you just kind of have to fight through it.”

Tide Pods are arguably one of the most successful innovations in the storied, 181-year history of consumer goods leviathan Procter & Gamble. They’re also the top-selling brand in a household-product category that became ubiquitous practically overnight. Eight years ago, liquid-detergent packets were barely a presence in U.S. stores; by 2018 they accounted for nearly one-fifth of the laundry detergent market and $1.5 billion in sales. And P&G, the maker of Tide Pods and another popular brand, Gain Flings, controls 79% of that business.

But the design factors that have made laundry pods so successful—their compactness, easy accessibility, and aesthetically pleasing look—are also potentially fatal flaws. Too often, it appears, young children and seniors with dementia mistake them for candy and try to eat them. And when that happens, they’re more likely than other detergents and other household cleaning products to cause serious injury.

Laundry pods’ threat to public safety became apparent immediately after their North America launch in 2012. Between 2011 and 2013, the number of annual emergency-department visits for all laundry detergent-related injuries for young children more than tripled, from 2,862 to 9,004.

The majority of injuries resolve within 24 hours without long-lasting effects. Still, pods make up 80% of all major injuries related to laundry detergent, according to the American Association for Poison Control Centers (AAPCC), despite accounting for only 16% of the market. In rare cases like Bella’s, long-term complications can ensue. And nine people have died in the U.S.—two children younger than age 2 and seven seniors with dementia—in cases definitively linked to laundry pods.To the extent that most consumers are aware of these dangers, it’s thanks to an asinine Internet trend. In late 2017 a handful of teenagers started posting videos online of themselves eating laundry packets in a surreal viral phenomenon known as the Tide Pod Challenge. That cultural episode cast laundry-pod poisoning as a self-inflicted wound, harming only the irresponsible. But the Challenge has accounted for only a tiny fraction of the injuries caused by this now pervasive product.

P&G and other detergent makers, startled by soaring numbers and prodded by regulators, have taken the product back to the drawing board more than once. But despite multiple changes to the pods’ design and exterior packaging, intensive industrywide meetings on the issue, and seven years of brainstorming and testing, the situation has not substantially improved when measured by the total number of calls to poison-control centers and emergency-department visits.

Pods have prompted an average of 11,568 poison-control calls a year involving young children since 2013, their first full year on the U.S. market. (The majority of calls, or exposures, involving pods are not associated with serious injuries, but they’re the best population-wide data available to measure pods’ impact on public health.)

And when injuries are inflicted, they remain disproportionately severe: In 2017, the most recent year for which figures are available, 35% of pod exposure cases among the whole population wound up being treated in health care facilities; for all other laundry detergents and for household cleaning substances, that figure was 16% when pods were excluded.

Consumer advocates and public health experts argue that, for all its well-intentioned efforts, the industry has refused to confront the brightly colored elephant in the room: the swirly, multi-hue design schemes that make the mini-packets look so much like candy. If manufacturers can bring themselves to make all pods look neutral and less inviting, says Gary Smith, director of the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, “we can design this problem out of existence.”

P&G and other detergent makers point to different injury measures, arguing that they’ve brought down the market-adjusted rate of exposures even without such changes, by improving the childproofing of packaging and educating the public on proper safety habits. “Our job is to prevent children from having access to the product completely,” says Damon Jones, P&G’s vice president for global communications and advocacy.

While they haven’t ruled out future changes, industry and regulators have announced no plans for a more aggressive safety intervention. But in an era in which many consumer-facing businesses have tremendous leeway to regulate themselves, the Tide Pod dilemma raises urgent and disturbing questions. Has P&G truly reached the limit as to how safe it can make its popular product? With no legal requirements to make pods safer, do ethics require the industry to go further? Can an “improved” product that still causes thousands of hospital visits a year be considered safe? And at what point does the manufacturer’s responsibility for accidents end and the consumer’s begin?

That these questions need to be asked testifies to a fundamental truth of America’s consumer product ecosystem: It’s largely up to companies to determine how to respond to a consumer hazard. While government agencies occasionally step in, safety decisions usually come down to business leaders balancing the success of a product against reputational and legal concerns. At least for now, P&G has made its determination: The Tide Pod is safe.

Consumer conglomerates like Procter & Gamble face a daunting challenge: They sell huge portfolios of famous brand names—in an era when many shoppers are happy to buy no-name brands to save a few bucks. By the early 2010s, that problem was becoming a drag on growth at P&G. And former employees say that Tide, a brand that dates back to 1946, was a case in point—no longer luring customers in its commoditized category. Laundry pods offered P&G a chance to restore Tide’s competitive edge.

Fortune spoke with nine former P&G employees about the Tide Pod’s development, and their accounts tell a consistent story about the process. (P&G declined multiple requests to make current executives available for interviews. Fortune spoke with the senior manager responsible for overseeing its pod safety efforts and conducted multiple conversations with the corporate communications team.) The idea of selling liquid cleaning agents in pre-measured packets wasn’t new: In 2001, P&G and Unilever started selling laundry pods in Europe that were larger than today’s versions. Former employees say that given the moderate success of these packets, as well as its dishwasher detergent tablets, P&G was confident that its more advanced Tide Pods would catch on in North America. Beginning in 2004, P&G embarked on a development process that it hoped would turn the product into a hit. Over the next eight years, the company would later boast, P&G dedicated 75 staff members to the Tide Pod project, involved some 6,000 consumers in market research, and generated more than 450 packaging and product sketches.

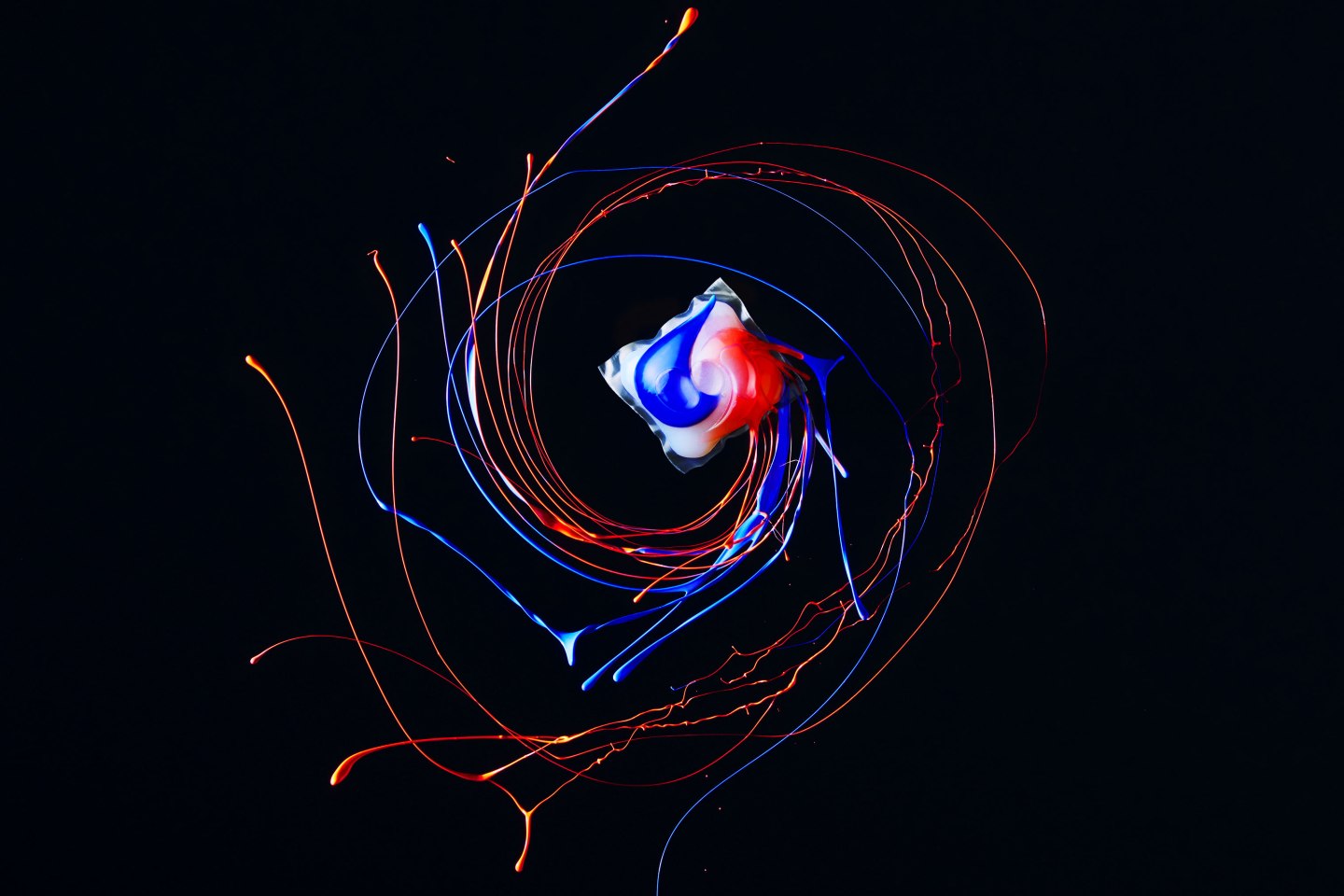

As the final shape emerged, the development team was thrilled with the results. Tide Pods were fun to hold—squishy, yet firm. Their colors—Tide’s signature blue and orange, in swirl-shaped chambers atop a white backdrop—stood out far more than the single-colored packets on the market at that point. And the pods came packaged in a clear tub, designed to show off the attractive design inside.

“We knew we had a breakthrough product on our hands,” says Tom Fischer, a former P&G executive for fabric and home care sales, the division responsible for Tide Pods.

The pods’ launch, in February 2012, proved them right. Shoppers seemed to love the convenience and the colorful form factor, and sales soared. In P&G’s 2012 annual report, released just a few months after they hit the market, then-CEO Bob McDonald proudly described Tide Pods as an example of “innovation that obsoletes existing products.” Between 2013 (liquid laundry packets’ first full year on the U.S. market) and 2018, pod sales grew 136%, according to Euromonitor International, a market research provider. During that period, the overall laundry detergent category grew just 7%. Today, pods make up close to a quarter of P&G’s overall laundry detergent sales.

A TV commercial that accompanied the Tide Pod launch in 2012 conveys the euphoria. In the ad, a woman draws a pod out of an open case and tosses it into the drum of a washing machine. In the background are sounds of bubbles popping and the upbeat Men Without Hats song “Pop Goes the World.” The spot ends with the tagline: “Pop in. Stand out.” But nowadays, popping is not an image P&G wants anyone to associate with Tide Pods.

Laundry detergent injuries spiked immediately after pods came out. In 2011 there were 8,186 calls to poison-control centers regarding laundry detergent exposures among the entire population, according to the AAPCC; in 2013, that figure rose to 19,753. Emergency-department visits related to laundry detergent for young children increased even more sharply. And each year since then, at least 85% of exposures and 79% of E.R. visits have involved children under age 6.

“The Tide Pod, as it’s designed, is an ideal product for attracting toddlers,” says Mariana Brussoni, a child psychologist at the British Columbia Children’s Hospital Research Institute. With laundry pods in general, “in terms of the colors they tend to have, the size, the feel, the fact that it can easily fit in their hands and their mouths—this is something that would be very appealing.”

Brussoni emphasizes that the risk would be greatest for children 1 or 2 years old, who are old enough to be mobile but too young to know what’s appropriate to eat. For kids that age, putting things in their mouth is “just another way of doing little experiments on the world,” and can also ease the pain of teething. Slightly older children, ages 3 and up, would be past that phase—but would recognize pods as looking like candy.

The most severe of the pod-ingestion cases have involved symptoms similar to the ones suffered by Bella Mancillas: An influx of fluid causes the lungs to flood and shut down, cutting off the flow of oxygen to the blood so severely that it can cause brain injuries such as seizures or comas. Some victims also suffer severe eye injuries from chemical burns.

There’s no consensus among health professionals as to precisely why pods have caused more serious injuries than liquid detergent has. One theory is that when the packets are bitten, their contents shoot into the throat with such force that they flow quickly down the trachea into the lungs. Another hypothesis is that the concentration of packets plays a role: Tide Pods, for example, have a 90:10 active-ingredient-to-water ratio, compared with about 50% water for liquid Tide. (Another complicating factor for health care workers: Manufacturers are not legally required to disclose all of their ingredients.)

When pods first came out and poison-control centers began getting calls, the centers followed the rules of liquid detergent poisoning: The person exposed was told to drink a bit of water, and the center would follow up after a half-hour, says Mark Ryan, president of the AAPCC. If there were no serious symptoms, the person exposed was not advised to go to a health care facility.

As poison centers increasingly witnessed severe injuries from pods, it became clear that those rules no longer applied. At the Louisiana Poison Control Center, which Ryan directs, he instructed call responders to follow up after only five to 10 minutes and monitor for respiratory issues. If those were detected, the caller was directed to go immediately to the nearest emergency room.

A few victims never got that far. Dennis Powers of Springfield, Ohio, was a kind, funny man who “never knew a stranger,” according to his daughter, Robyn. A Navy veteran and die-hard Ohio State Buckeyes fan, Dennis was diagnosed with dementia in 1999. He was still in relatively good physical health on Feb. 15, 2014, when his wife, Darlene, dropped off some groceries at home, including a pouch of Tide Pods, and went out to get more supplies.

When she returned a few hours later, Darlene says, she found Dennis slumped over the back of his white rocking chair. The chair was covered in orange dye, and there was detergent coming out of Dennis’s mouth. He barely had a pulse. Darlene called 911, but EMTs couldn’t revive Dennis and pronounced him dead at the scene. He was 67.

Dennis’s autopsy report declares that he died from asphyxiation resulting from ingesting a pod. Of the 31 pods that came in the pouch, five were missing: Two were found on the floor next to Dennis’s chair, one in a drinking glass, and one in the trash can; all appeared to have been chewed. The report concludes: “The remaining pod was not found.”

Recounting the incident at her lawyer’s office in Ohio, just before the fifth anniversary of Dennis’s death, Darlene struggles to keep her composure. The only reason that could explain why Dennis ate a pod, Darlene and Robyn say, is that they look like candy. “He was used to eating swirled Life Savers,” says Darlene.

P&G says today that it had no unique concerns about the safety of Tide Pods at launch, given the lack of any poisoning crisis in Europe. Rick Hackman, head of North America regulatory and technical external relations at P&G, says that the company applied the same stringent safety process to the pod launch that it does to all its products.

Yet P&G took an additional step that seemed to indicate an unusual degree of caution. Immediately after the launch, the company enlisted the Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center to collect data on exposures. In response to questions from Fortune, P&G says that a panel of external medical advisers recommended the data collection because the product was new to the market. (P&G also says the company took similar action when it introduced dishwasher packets, which are similar in size and shape.)

P&G declines to say whether the commissioning of the Cincinnati data collection reflected concerns that the product was uniquely risky. But Richard Dart, head of the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center at Denver Health and an expert in the field of consumer safety for over 30 years, describes this as highly unusual. With “prescription drugs, if the FDA has concerns, they will require monitoring right from the minute it enters the market,” he says. “But for consumer products, especially, I don’t think I’ve ever even heard of one that did this.”

In regulatory circles, meanwhile, the surge of pod injuries was dramatic enough to draw attention. In October 2012 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a warning to consumers that laundry pods, which had a “candy-like appearance,” were “an emerging public health hazard.” In March 2013 the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) issued a statement calling on the industry to take voluntary action to address the hazard. While the CPSC has wide regulatory powers, including the ability to force a mandatory recall or unilaterally develop safety standards for a product, it uses these levers only in rare instances when a product is patently dangerous, says Cheryl Falvey, a partner at Crowell & Moring and former general counsel at the commission. Otherwise, she says, the commission prefers to nudge businesses and consumer advocates to come up with voluntary standards, which, despite their name, manufacturers are required to follow. And even in that context, the CPSC’s call for action on pods was relatively unusual—something that Falvey says happens only once or twice a year at most.

While other manufacturers also make laundry pods, P&G as the market leader took the lead role in responding—and by most accounts, the company’s actions were serious, urgent, and diligent. By mid-2012 it had already begun installing double-latch lids on the tubs containing its pods. And by the summer of 2013, P&G had changed the tubs’ design to be opaque, placating critics who felt the clear tub resembled a candy jar. Still, the number of poisonings kept climbing. In February 2015, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and Rep. Jackie Speier (D-Calif.) introduced federal legislation that would have forced manufacturers to make the design of packets “less attractive to children” and use less caustic ingredients.

The legislators noted that they would drop the bill if the industry took stronger action on its own. In September 2015 that effort took concrete form as manufacturers, industry lobbyists, and consumer advocates approved a new set of safety rules. The standards required that pods have opaque, difficult-to-open packaging; standardized warning labels and safety icons on packages; and burst-resistant, bitter-tasting outer film.

By 2017 the new standards had been implemented across the industry. And in June 2018 the standards committee met again to review injury numbers and determine their progress. The results they saw, depending on one’s point of view, were either a reassuring sign or an indictment of a failed safety system.

The studies measured the impact of the industry’s safety intervention on children under 6, comparing a 12-month period before the new measures went into effect (July 2012 to June 2013) to a 12-month period after the intervention (calendar year 2017). During that time span, the number of pods sold more than doubled, from 2.1 billion to 4.7 billion, according to Nielsen data used in the reports. The upshot: The ratio of exposures to total pods sold dropped 53%; the ratio of exposures involving health care facility treatment to sales dropped 63%; and the ratio of exposures involving major medical injuries or death to sales dropped 86%.

For the industry, these were an important sign of progress. But consumer advocates at the same table saw a glass half-empty—because while injury rates, measured by market size, were down, injuries as measured by absolute numbers (and when adjusted for population growth) barely budged. Annual emergency-department visits dropped only slightly over that span, from 4,300 to 4,200, while total exposures actually rose slightly, from 10,229 to 10,776. (Exposures dropped to 9,440 in 2018, according to preliminary AAPCC data, but those numbers are likely to rise slightly once the data has been fully analyzed.) And the share of total exposures involving health care facility treatment—a measure of injury severity—dipped slightly, from 42% to 33%.

As Rachel Weintraub, legislative director and general counsel for the Consumer Federation of America, notes, the reports “gave both sides data, to pursue either their views that it was working very well, or views that more needed to be done.” Today, P&G cites this data as evidence that the industry’s approach is successful. “As long as we continue to see reduction in incident rates, even if the number of [poison-control] calls increased, we would think of it as progress, as the form is new and people are learning how to use it,” Damon Jones and Petra Renck of the P&G communications team told Fortune in an email.

Consumer advocates, meanwhile, argue that the industry is setting the bar too low. Measuring progress relative to market size is an incomplete measure of success, says Gary Smith, the injury expert at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, who has been part of the standards process. For 150 years, epidemiologists have used the absolute number of cases, or the number of cases relative to the population at risk, to measure public health burden, Smith says. “If this were Zika virus, and the number of cases of encephalopathy were still going up, but the number of cases per mosquito population were going down, we would take no comfort in that latter number.”

The standards group plans to meet again in mid-2019 for another progress review. Both sides hope to see further improvement, but that’s uncertain. Richard Dart, the Denver poison-control expert, notes that the decline in exposures has already started to slow. “We’d like the number of incidents to go down, and that’s how we look at public health measures across the board,” says Weintraub.

However one interprets the statistics, one thing is undisputed: The industry didn’t alter its approach to color. Tide has changed its signature color scheme to white, blue, and green from orange, blue, and white, but P&G says that change was not safety related. Indeed, the multihued whorls that critics see as so candy-like are still the norm in the laundry-pod world.

P&G has long argued that research shows the appearance of packets doesn’t play a role in exposures. Asked to describe that research in greater detail, P&G cites two studies conducted by the Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center—both relying on the data that the organization began collecting at P&G’s behest when Tide Pods launched.

On closer inspection, those studies don’t resolve the question. P&G provided Fortune with a copy of the first study and sent excerpts from the second, which has not been published. The unpublished study found that when examining pods based on color (single vs. colorless) and design (single-chamber vs. multichamber), the ratios of exposures roughly matched the ratios of market share—so, for example, multichamber pods made up about 70% of exposures and 70% of market share. The other found that colorless and single-color packets caused roughly the same number of exposures for children under 6 when controlled for market size.

P&G says it’s confident that these two studies offer sufficient evidence that appearance isn’t a factor in pod-related injuries. Arthur Caplan, founding head of the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU School of Medicine, disagrees. Caplan says that manufacturers have to “use the best science” to make their products safer, and that relying on one data set, as P&G appears to have done, is not a sufficient approach. The company, Caplan says, should also examine “data from other products that bears on this question.”

To prove or disprove a connection, health professionals say, P&G would need to study how pods’ smell, feel, and appearance—including Tide Pods’ multicolored swirls—appealed to vulnerable populations. For example, “you would need to do a randomized controlled trial, varying pod designs and monitoring reactions to them” to know for sure which factors attract young kids, says Brussoni, the child psychologist. “But to my mind, why bother? Why have these colors anyway for a product for an adult that’s doing laundry?”

For now, such research doesn’t appear to be in the cards—for any manufacturer. Jones disputes the premise of studies like those described by Brussoni. “We don’t put two different pods in front of a kid,” P&G’s Jones says, “and say, ‘Grab one.’ It’s not a real-life situation.” Rather than changing the pod design, P&G has stressed in its conversations with Fortune that making packaging more secure and educating caregivers about safe use are the most important measures it can take to improve safety. Henkel, whose laundry detergent brands include Persil and All, declined to discuss possible safety improvements but said it was compliant with the current voluntary standard. Church & Dwight, whose brands include OxiClean and Arm & Hammer, did not respond to Fortune’s requests for comment.

Vincent Weill, who led P&G’s efforts to incorporate design innovations into the Tide Pods product between 2012 and 2017, and who now works at a company that is not a competitor, tells Fortune that he was involved with projects to make pods safer that have continued since he left the company. Among them were reformulating the liquid to be less toxic and strengthening the packets to be more resistant to bursting or leaking.

P&G declined to comment on the projects described by Weill or any other specific possible changes. Jones describes the company’s effort to make pods safer as an “ongoing journey” of continual improvements.

In multiple exchanges with Fortune, P&G emphasized its efforts to educate the public on how to use pods safely—through labeling, advertising, in-person safety education sessions, and the blogs of influencers the company works with. When the Tide Pod Challenge became a sensation in late 2017, injuries were few, but the negative publicity was immediate—and P&G’s response was swift. The Tide Twitter account admonished teenagers never to eat packets. The company quickly produced a TV spot featuring All-Pro New England Patriots tight end Rob Gronkowski, lecturing, “Use Tide Pods for washing, not eating.”

P&G’s emphasis on education is a kinder, gentler version of a defense that’s common to consumer product manufacturers: that shoppers are ultimately responsible for using products properly—or not. But consumer advocates chafe at the implication that the primary fault for pod injuries lies with parents and caregivers. With a mass-market product like this, says Caplan, the ethicist, “the duty is there, when any product enters the household, to make sure that it is as safe as can be.”

Consumer advocates are adamant that detergent-makers haven’t cleared that bar. What’s more, says Gary Smith, the injury expert, American society has largely bought into the belief that household injuries are entirely about personal responsibility. “When you talk to a parent whose child has been injured and brought into the emergency department … they will tell you, ‘It wasn’t the product, doctor. It was me. I’m a bad parent. I didn’t watch my child carefully enough,’ ” Smith says. “They’ve bought the myth that it’s them that’s the problem.”

For now, federal regulators appear largely satisfied with the industry’s recent improvements. In an email to Fortune, CPSC spokesperson Patty Davis wrote approvingly of the 2017 data that “showed statistically significant declines in hospitalization rates and in [emergency-department] visits per product sold”—the same numbers P&G cites—though Davis also noted that the commission wants to keep working with the safety standards group “to reduce the unreasonable risk of ingestions.”

State and federal legislators may try to crack down more firmly. Aravella Simotas, a former lawyer who now represents a Queens district in the New York State Assembly, recalls her alarm a few years ago when her then 1-year-old daughter picked up a Tide Pod that had fallen on the floor. “She was looking at it very closely,” says Simotas, who grabbed it before her daughter could get hurt. “You have to understand, my child never put anything in her mouth.” In February 2018, Simotas and Brad Hoylman, a state senator from Manhattan, sent a letter to P&G calling on the company to change its designs and threatening to press for legislation that would ban all laundry detergent pod sales in the state “unless pods are designed in an opaque, uniform color; not easily permeated by a child’s bite; and individually enclosed in a separate child-resistant wrapper” with a warning on it. In a phone interview, Hoylman references the Tide Pod Challenge: “I’m not trying to protect stupid teenagers from making viral videos about Tide Pods. I’m trying to protect young children.”

If New York were to pass a bill, of course, its scope would be limited to one state. Legislative action at the congressional level is something consumer advocates aren’t counting on, since the odds of a laundry-pod bill being passed by a Senate that’s skeptical of regulation, and signed by a President who has vowed to reduce the regulatory burden on companies, seem slim.

It’s too early to tell whether private lawsuits could move the needle further than the government has. Richard Schulte, an attorney with Wright & Schulte who is bringing legal claims on behalf of the Mancillas and Powers families, says his firm is attempting to reach settlements with P&G outside the court system on 70 cases. He says the firm has resolved all of its claims against other pod manufacturers out of court.

The main reason there aren’t many lawsuits against pod manufacturers, Schulte says, is that most lawyers don’t know how dangerous the product is. “When I tell other top trial lawyers, confidentially, that I’m bringing claims against the pod manufacturers, they look at me like I’m a martian,” he says. Furthermore, most pod-related cases involve injuries that are not life-threatening and thus won’t command large payouts if they win.

P&G declines to comment on whether it has paid any out-of-court settlements. Tellingly, P&G has never mentioned Tide Pod litigation as a business risk in its 10-K filings, going back to 2012, the year its pods were launched. (In contrast, Johnson & Johnson’s latest 10-K has a long section on liabilities that describes, among other things, the financial risks incurred through lawsuits that have linked J&J’s talcum powders to cancer.)

That leaves the court of public opinion, where P&G will presumably suffer only if it’s perceived as not putting the safety of its customers first. Pod sales growth has slowed at P&G since the product’s heady early days, but sales were still up 4.4% year over year in 2018, at $1.17 billion, per Euromonitor, and the company’s stock hit an all-time high in early February.

Consumers, meanwhile, are left to make calculations of their own about the value of convenience versus risk. That math is still playing out in the lives of Katie and Bella Mancillas. Katie says that arguments with Bella’s father about the poisoning incident contributed to the divorce they’re going through. Only 23 years old at the time, Katie dropped out of college to take care of Bella. She is now studying to be a social worker.

Katie’s own conclusion about laundry pods: “Take the extra five minutes to pour the laundry [detergent] yourself. It’s not worth losing your children.”

This article originally appeared in the March 2019 issue of Fortune.

Due to an error in source material, the print version of this article incorrectly cited the share of total laundry pod exposures in 2017 that involved health-care facility treatment; it was 33%, not 39%. This version also clarifies statistics about the increase in emergency-department visits related to laundry detergent after laundry pods first hit the U.S. market.

If you believe you or someone you are with has been exposed to a poisonous substance, please call Poison Control at 800-222-1222 or visit www.poisonhelp.org.