Join or Sign In

Sign in to customize your TV listings

By joining TV Guide, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge the data practices in our Privacy Policy.

Better Call Saul Paid Its Debts

The Breaking Bad prequel faced the music in a tragically romantic series finale

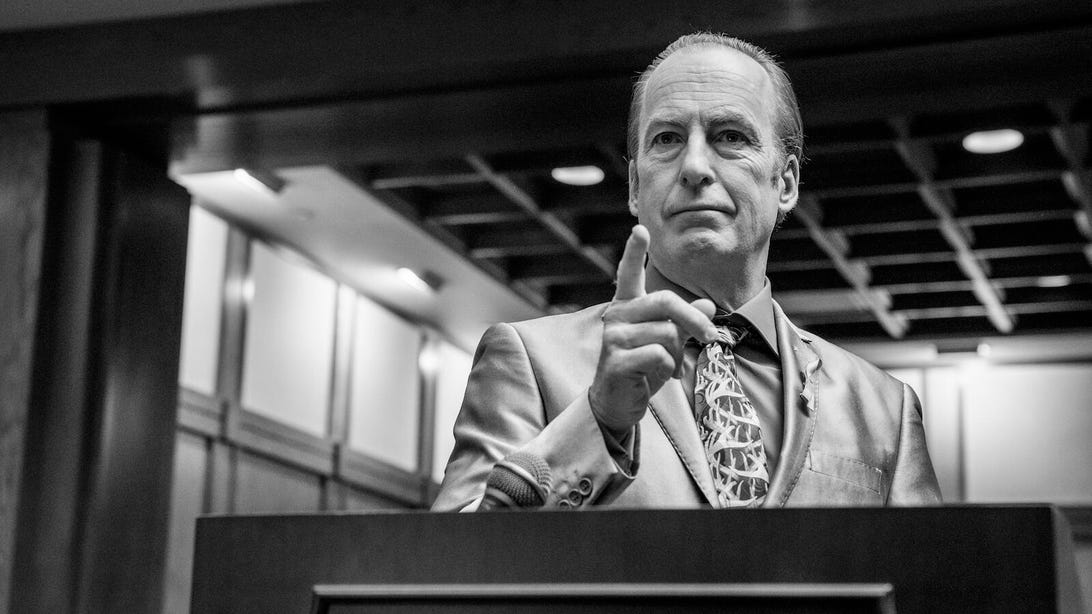

Bob Odenkirk, Better Call Saul

Greg Lewis/AMC/Sony Pictures TelevisionGene Takovic is trapped. The man who was once Jimmy McGill (Bob Odenkirk), born again as technicolor crook Saul Goodman, is stuck in a monochrome new life as a Cinnabon manager in Omaha, but he is also, in the Season 2 premiere, literally stuck, locked in the trash room at the mall and unable to open the emergency exit for fear of alerting the police to his existence. By the time he gets out, he's scratched "SG WAS HERE" onto the wall.

I thought a lot about that scene during Better Call Saul's thrilling, brutal sixth and final season, which wrapped up Monday with a finale so sincere it cut to the bone. Peter Gould and Vince Gilligan's Breaking Bad prequel was, not unlike its predecessor, about a man's macabre transformation into his most horrible self. But it was built to be more reflective, a prequel staring its future in the mirror. Its final hour peppered in multiple conversations about time travel, the fantasy of going back to fix past mistakes: a great gag for a series about characters who feared their fates were already written. In many cases, they were. But Jimmy's life in hiding as Gene Takovic represented an escape hatch for the writers, a crack in a tale that seemed to be set in stone. Through Gene, Better Call Saul found a time machine. To follow the internet's favorite Greek philosophical thought experiment, the AMC drama answered the Ship of Theseus question through Jimmy McGill, who remade himself into a series of new identities but was incapable of leaving his previous selves behind.

The final episodes broke from Saul's usual format. Most of the series had resisted the urge to flash forward to the Breaking Bad days — what the writers called "dancing through the raindrops" — sticking instead to the early 2000s, a few years before Saul Goodman met Walter White (Bryan Cranston) and Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul). The show was already loaded with anxiety about whether it's possible to rewrite your life; Saul loomed whether we saw him or not. But when Jimmy's wife, Kim Wexler (Rhea Seehorn), left him in the wake of tragedy, Jimmy shut down, disappearing behind his Saul Goodman mask. The criminal lawyer was reintroduced in all his combed-over glory after a bleak time jump at the end of Episode 9. And then — the series swerved again, skipping over most of the Saul era in favor of the black-and-white fable of Gene, a lonely man relapsing in his addiction to scamming. SG was still here.

Bob Odenkirk, Better Call Saul

Greg Lewis/AMC/Sony Pictures TelevisionSeeing Jimmy become Saul was a gut punch. Seeing Gene become Saul was somehow worse. You want to believe people can learn from their mistakes, not double down on them. In the lead-up to the end, the conversation around Better Call Saul was preoccupied with the question of what kind of fate Jimmy deserved. Fitting, then, that as soon as viewers had seen him at his old lady-menacing worst, the finale — perfectly titled "Saul Gone" — sent him back to court to be judged for his crimes. He wore his flashiest Saul Goodman costume to the sentencing hearing and asked to be addressed by the name that made him infamous, but it was one last con. When he, while Kim looked on, confessed to the greed that drove his alliance with Walter White, Jimmy became Jimmy again in an effort to be worthy of the love of his life. He couldn't let go of Saul on his own, but he could do it with Kim watching.

This is what strikes me most about Better Call Saul: how connected everybody was. The show insisted that its characters own up to the consequences of their actions as individuals, but it was equally clear-eyed about how difficult it is to act alone. Jimmy's frustrated love for his older brother, Chuck (Michael McKean), motivated his early attempts to go legitimate, as well as his self-sabotaging backslides after Chuck rejected him. Jimmy and Kim, one of TV's most fascinating romances, pushed and pulled between destruction and redemption. Fatally turned on by running scams together, they took turns worrying that they were bad for each other. They were clearly bad for their former boss, Howard Hamlin (Patrick Fabian), whose death Kim and Jimmy unintentionally set in motion when they schemed to ruin his reputation. They didn't pull the trigger, but they weren't free to abandon responsibility either; the story couldn't end as long as they did.

Better Call Saul Stars and Showrunner Reflect on the Series Finale

It was almost a rush when Kim walked away, if only because taking responsibility for the harm you've caused is the moral imperative of the Better Call Saul universe. Her split from Jimmy was devastating, but watching her lose any more of her integrity would have been even more so. But the sick satisfaction of doing penance faded in light of the punishment Kim chose for herself: a small life working at a sprinkler company in Central Florida, wearing socks with pom-poms on the ankles, denying herself the right to make any decisions that might affect the people around her. Kim didn't change her name, but in stripping herself down to a suburban shell of a person, she imprisoned herself the same way Gene did. "Waterworks," the episode that introduced Kim's new life, was stunning, and also possibly the saddest episode of television I've ever seen. If love is strong enough to annihilate the people around you but denying yourself love is an annihilation of self, what's left?

Kim's story was defined by her agency. "You don't save me. I save me," she told Jimmy in Season 2. To Howard, she insisted in Season 5, "I make my own decisions, for my own reasons." It was hard to imagine a crueler fate for her than to lose faith in her voice. Fans spent years worrying Kim might die, and Better Call Saul found something worse: Kim Wexler couldn't even have opinions about mayonnaise. But it was no wonder she was afraid to speak up. The world of the show was a complex Rube Goldberg machine in which actions reverberated years down the line. In a clever meeting between the two halves of the Breaking Bad universe, a scene in "Waterworks" brought Kim together with Jesse Pinkman, who revealed that Kim once defended his friend Combo (Rodney Rush) as a pro bono client. Combo would go on to steal the RV that jump-started Walt and Jesse's meth empire. What if he was only in the position to steal it because Kim kept him out of juvie? What if Kim, by vouching for Jimmy's legal skills to Jesse, delivered that meth empire to her ex-husband's door, right after signing the divorce papers she hoped would keep them both from hurting more people? Wherever she went, there she was.

Rhea Seehorn, Better Call Saul

Greg Lewis/AMC/Sony Pictures TelevisionIt's impossible to disentangle yourself from the world. This was the idea at the core of Better Call Saul, so powerful it reshaped Breaking Bad, too. Behind the story of Walter White's quest for power, there was Saul Goodman, who saw Walt as clay in his hands. Neither one of them knew the bodies of Howard Hamlin and Lalo Salamanca (Tony Dalton) were buried under Walt's feet in Gus' (Giancarlo Esposito) lab. At the risk of oversimplifying Breaking Bad a little, on that show the buck mostly stopped with Walt, who ruined the lives of those around him even after he was handed another way to pay for his cancer treatments. He admitted in the end that he did what he did because he liked it. Jimmy's confession in "Saul Gone" seemed similar on the surface: "I saw opportunity," he said of the night he met Walt. But Jimmy showed remorse in the end, accepting the judgment of the legal system that he'd twisted for his own gain. He recognized the bodies beneath his feet.

The camera zoomed in and pulled back to capture the context. The Breaking Bad universe was known for its wide shots, and Saul had a thousand great ones: suffocatingly empty desert vistas and mildly foreboding geometric office buildings. There were clever close-ups, too, framing the characters as if behind bars. The visual language of the series boxed people in, only to turn around and make them giants — one scene in Season 5 zeroed in on a parade of ants living it up on an ice cream cone Jimmy dropped on the sidewalk. From the right perspective, the characters could be victims or gods.

There was doomed cartel member Nacho Varga (Michael Mando), unable to escape the life he'd chosen without risking the life of his father (Juan Carlos Cantu). There was Mike Ehrmantraut (Jonathan Banks), haunted by his past sins as a cop but digging himself deeper into the dirt to make money for his family. Over six seasons, Saul gradually teased out Kim's childhood with an alcoholic mother (Beth Hoyt), giving texture to her resentment of the legal elite. Kim wanted to build a pro bono practice that could be a beacon of justice for the little guy, but like Jimmy, she lost her patience for doing it by the book. Her desire to exert real control over a rigged system drove her to scam alongside Jimmy, then curdled into something more plainly selfish. As for Jimmy, his addiction to cutting corners was a fatal flaw as often as it was his clients' only hope. Think of his defense of the elderly residents at the Sandpiper Crossing retirement community — Jimmy did his best and most valiant legal work by dumpster diving.

Bob Odenkirk, Better Call Saul

Greg Lewis/AMC/Sony Pictures TelevisionProfiling Bob Odenkirk for The New York Times Magazine in February, Jonah Weiner wrote, "One of the more provocative implications of Better Call Saul is that Jimmy's truly unforgivable transgression isn't that he behaves unethically but that he does so as an uncouth underdog." Even Chuck, a legend in the Albuquerque legal community, scammed people. Jimmy's greatest offense was that his bootstraps were too cheap. The Season 4 finale gave him a mirror in the form of a teenage girl whose one shoplifting transgression would follow her forever; the establishment was never letting either of them in. It's harder to justify playing by the rules when they uphold a rotten status quo.

But so what? Kim left Jimmy accepting that they still loved each other, but what was that worth if their love story had a body count? Similarly, Better Call Saul put its characters in a frustrating justice system — such an American tale, half neo-Western and half noir — that limited upward mobility, denied forgiveness, encouraged corruption, and failed to protect the elderly and powerless. Most moral downfalls on Saul began with caring about someone. And yet this wasn't absolution; it was just a tragedy. Even when there were no good options, the characters still had to live with their decisions when they were alone.

The final episodes dispensed with the excuses: Jimmy and Kim had to own up to the consequences of their actions, not as gods or victims but as people. Their repentance, like their self-destruction, was intertwined. Because Jimmy called her and urged her to say something real, Kim returned to Albuquerque and admitted to her role in Howard's death — which meant nothing to the D.A.'s office but certainly meant something to Howard's widow, Cheryl (Sandrine Holt), who closed the series with the power to sue Kim for all she was worth. Kim's willingness to put her fate in Cheryl's hands inspired Jimmy to clear his conscience on the record, publicly telling the truth not just about his partnership with Walt but — finally — about how he nudged Chuck toward his death.

The price of the truth was a life sentence, bumping Jimmy's prison term from seven to 86 years. There was some poetic justice to the showman lawyer tearing up his own Get Out of Jail Free card, and a sweet grace note in his apparent folk hero status behind bars, but the real victory was personal. It fell to James Morgan McGill to choose what he deserved: his own name back. Kim's confession also freed her to reclaim something of herself; even before Jimmy's hearing, she rediscovered her agency by taking up volunteering at a free legal aid clinic. Jimmy and Kim, whose relationship at its best was a rare refuge for honesty, reconnected with the world and with each other by taking off their masks.

Bob Odenkirk and Rhea Seehorn, Better Call Saul

Greg Lewis/AMC/Sony Pictures TelevisionIf the characters of Better Call Saul could only be damned by their shared humanity, it's equally true that they could only be saved by it. The lowest and most painful scene in "Waterworks" found Kim breaking down on an airport bus, recognizing that nothing she could do could erase her mistakes. A hand appeared on her arm while she sobbed, comfort from a stranger sitting out of frame. Speaking to TV Guide in 2020, showrunner Peter Gould summed up Better Call Saul's approach to holding the audience's attention as a prequel: "Our theory was that how things happen is even more interesting than what happens. You can synopsize anybody's life by saying, 'She was born, and then she died.' But it's the experience of it." It's a sentimental thing to say about a show that found its emotional weight in the straightforward act of living, but the experience of Better Call Saul was a hand on an arm when you didn't expect one. A story about whether it's possible to change resolved that question through people's responsibility to each other.

What happened was that Kim went to Florida and Jimmy went to jail. Counting both the bloody final season of Saul and the events of Breaking Bad, every other series regular on Saul was killed. How it happened, though, allowed for measured hope. The finale brought Jimmy and Kim to a place of understanding, granting them one last (on-screen) smoke together in a callback to the series premiere — a loaded scene that let the show's visuals do most of the talking. Their lives stayed black and white, but the flame between them was lit in color. It might have been a remnant of their past or a sign for their future, but the finale dispensed with time travel anyway. The end of Better Call Saul was not an ending; it was a spark of something in the present.