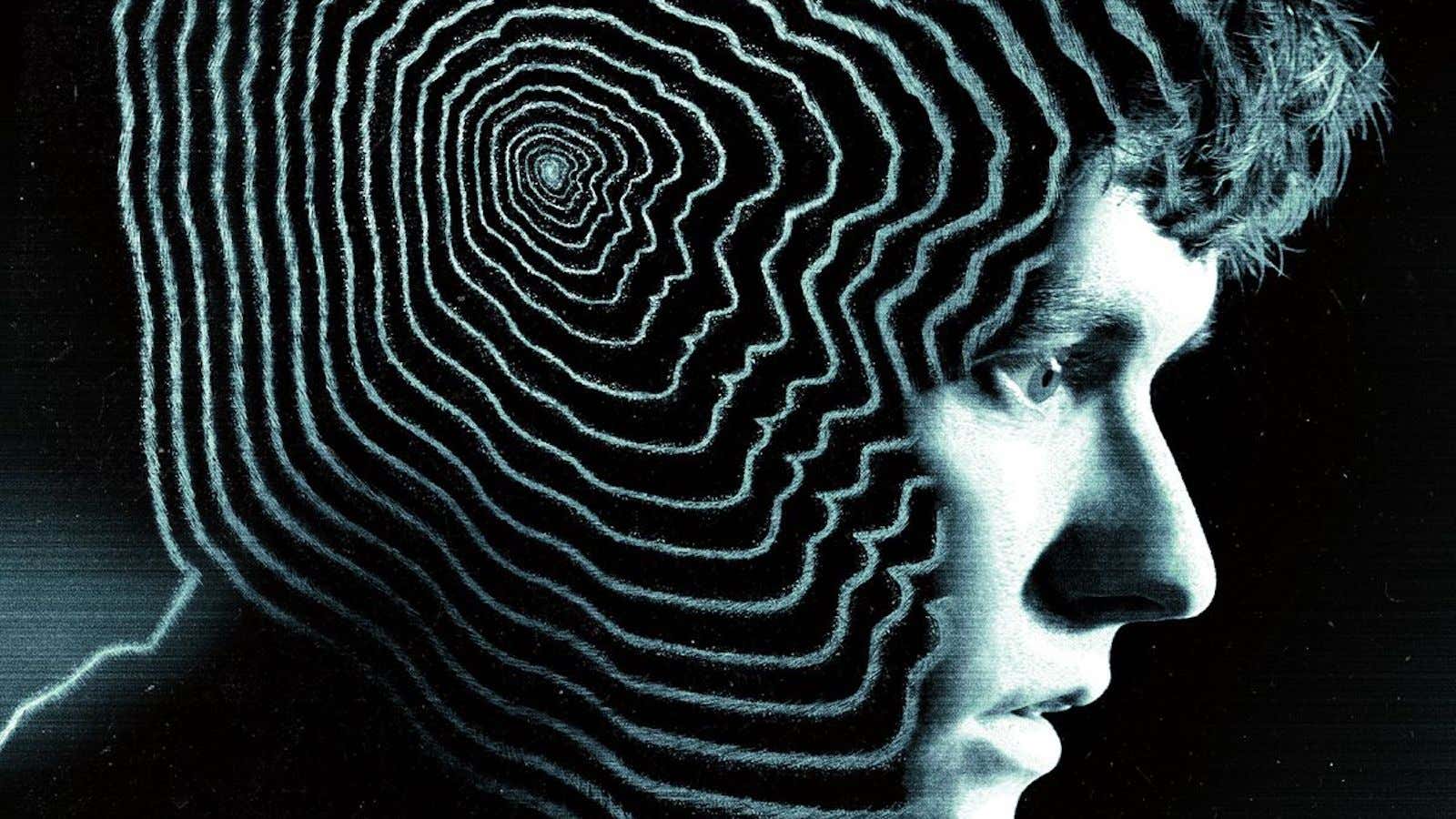

Black Mirror, the TV series written by the smart and gloomy Charlie Brooker, appears to routinely predict and dramatize world news and policies. But instead of merely predicting the future, the newly released “Bandersnatch” could be creating it.

Released on Netflix on Dec. 28, “Bandersnatch” charters new territory. Yes, it’s one of the first mainstream attempts at narrative-driven gameplay on a streaming platform. But it’s also potentially the progenitor of a new form of surveillance—one that invades our privacy while wearing the cloak of entertainment.

Instead of just passively watching a movie, the viewers (or players) get to choose what the main character does next. Some choices are seemingly innocent—what music to play, what to eat for breakfast—but then quickly moves on to questions about career decisions, mental-health issues, and even whether to kill other characters.

All this data is collected by Netflix and stored in a secure database. (Though with so many recent hacks of other companies, it can be hard to feel assured.) Your choices are used to improve the gameplay; those seemingly innocent early decisions (like whether you chose Sugar Puffs or Frosties) impact the narrative much later in the story. Without collecting this information, it can’t send you down your personalized journey choose-your-own-adventure journey.

But what happens to your decision data after the credits roll?

Netflix acquires a lot of data about its users. This includes information about your viewing habits on the platform, like the programs you choose to watch and how long you watch them for. It uses this data to recommend new shows it thinks you’ll enjoy, as well as to improve its customer service and for marketing purposes.

But what if instead of logging how many times you watched Love Actually this holiday season, it’s remembering whether you opted to kill your father in cold blood, or save him? What could Netflix do with that highly sensitive emotional information?

“The privacy of Netflix members is a priority for us,” a Netflix spokesperson said in an email. “Documenting choices improves the experience and interactive functionality of Black Mirror: “Bandersnatch.” All interactions with the film and uses of that information are in compliance with our privacy statement.”

When reading through Netflix’s privacy statement (and also the statement about its recommendation algorithm), it isn’t clear whether the data of the viewers’ choices will be used outside of the actual game. Privacy policies like these are vague and undetailed because the algorithms change so regularly that it’s impossible to include every single data point in the document.

But should data on the shows you choose to binge watch be treated the same as more serious behavioral choices, such as whether commit murder or leap off the edge of a building? If the gameplay data is considered different to the data that Netflix already collects, under the GDPR (an EU data protection regulation), Netflix would have to notify its EU users about the change in data collection. But there’s a chance its privacy policy is broad enough that Netflix doesn’t have to.

So what? you might ask. When you play “Bandersnatch,” is it really reflecting your true nature, anyway? Are you choosing to attack your therapist because you have deep-seated anger issues, or is it just for entertainment value? Many decisions lead to dead ends, which means that you have to go back and make a different choice again anyway. Do your choices in the show really reveal that much about you?

It matters for three reasons. One is because Netflix has a huge influence over how millions of people get cultural and political information. In September 2018, they had 137.1 million subscribers, all of whom are plugged into the recommendation algorithm. Users are far more likely to watch programs that have been recommended to you, and this in turn changes how you perceive the world.

Your decisions in interactive films could have many unintended consequences. If Netflix determined that those who immediately chose to kill a family member in “Bandersnatch” would be more likely to enjoy the film Kill Bill Vol 1, then this data could be used to serve you more violent films. Netflix is planning more interactive content in 2019—and it’s already been running interactive kids’ content for years. This will allow them to gather more instinctive behavioral data on a variety of subjects. What if it started serving you programs celebrating a particular political party because of the choices you made in an interactive White House thriller?

Secondly, it’s not hard to imagine that companies that do collect information about you to share with political actors—like YouTube and Facebook—will forage into this media form in the future. The data from personality quizzes have already caused huge ramifications for political elections—so what about interactive gameplay? It offers a new way of understanding users’ personalities, and what they are likely to respond to.

The third concern is the most Black Mirror of them all. It’s not inconceivable to imagine that if the government got a hold of your data, it could think you’re someone worthy of future surveillance. Studies from the Oxford Internet Institute show that there is little evidence to say that playing violent video games lead to violent real-life behavior. However, there are still politicians that peddle this narrative. Could Netflix data be used to identify future terrorists or restrict your access to airports? It’s not dissimilar to China’s “social credit system,” where individuals can be judged and punished for not paying bills or jaywalking.

Black Mirror’s “Bandersnatch” dissects the idea of free will. But another parallel theme is the erosion of our own real-life privacy. Instead of choosing your own adventure, what if Netflix is choosing for you?

Black Mirror could be watching you. And its stories do not generally have a happy ending.