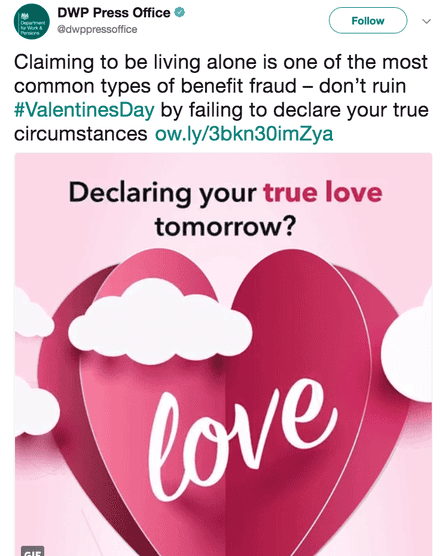

When the Department for Work and Pensions last week decided to issue a Valentine’s message to people on benefits – clearly implying that recipients lie about their “living arrangements” to fleece the state – it was the latest attack designed to blame and shame. It is a well-worn pattern, especially for people who qualify for benefits.

Since the emergence almost a decade ago of the poisonous rhetoric of “skivers and strivers” that has helped to prop up the fiasco that has been Tory austerity, a culture of dismissing poor people has become well and truly entrenched. The despicable idea that being poor is somehow the byproduct of personal flaws rather than bad policy, and that strong welfare systems should be rejected, is pervasive.

How else to explain the fact that food banks have become normalised or that the repeated denial of benefits – and dignity – to people with disabilities has failed to provoke a nationwide revolt? How else to compute that a homeless person dies on the doorstep of the Houses of Parliament and registers only as a temporary blip on the national consciousness?

Somehow, we have come to a point where what should be unpalatable is acceptable. All of this should tell us that we need to radically alter the national conversation around poverty – and we need to start right now. The sorts of policies that produce spikes in street homelessness and see hundreds of thousands of families living in substandard accommodation, or that usher in drastic cuts to social care and mounting crises within the NHS, are intimately linked to the wider tone set on poverty and the welfare state’s role in alleviating it.

In the US – which barely has a welfare safety net and which is the ultimate poster boy for British advocates of rolling back the state – the campaign to demolish what little support there is for poor people has reached a new crescendo. And, as with austerity in the UK, cruel and counterproductive policies are wrapped in language carefully crafted to demean and “other” those in need of assistance.

Since the start of the year, the Trump administration has launched an all-out policy assault on America’s poor. The opening salvo came when Medicaid, the national social insurance programme providing essential health benefits for about 74 million Americans – was subject to a brazen, calculated attack.

It isn’t enough that Republicans have been trying to demolish the 50-year-old programme (despite it being effective as well as popular nationwide) for decades. With a new set of guidance issued by the administration last month, unless legal challenges are successful, individual states will be able to take healthcare provided by Medicaid away from people unable to find a job who fail to meet certain “work requirements”. Early estimates suggest that as many as 6.3 million people could lose access to healthcare.

It takes to a whole new level the toxic strategy of withholding benefits from supposedly entitled poor and disabled people or punishing them with sanctions. As Jonathan Schleifer, executive director at The Fairness Project – a non-profit that works for economic justice – points out, it is “stigmatising”poor people further via a “politically motivated attack” predicated on a mythology that they are workshy.

In the early days of austerity Iain Duncan Smith’s DWP framed the slashing of the welfare state as welfare reform in order to sell it to the public as an improvement that would prevent the system being exploited. This tactic was straight out of the American playbook from the mid-1990s when Bill Clinton all but ended the welfare system under the guise of reform, only to exacerbate poverty.

Now, like a twisted pinball game, politicians on the right in the US are back on the so-called welfare reform bandwagon with a vengeance. Trump’s budget was nothing short of all-out war on poor people, with savage cuts proposed to everything from nutrition assistance to affordable housing.

And how are they trying to sell their proposed cuts to vital programmes that help the poor? You’ve guessed it. It’s all about framing. The speaker of the House of Representatives, Paul Ryan, has been cheerleader-in-chief, wheeling out phrases such as “helping people” and positioning cuts to Medicaid as a boon for “workforce development”. Others justify the proposals by saying it’s all about promoting individual fulfilment.

This pernicious, repetitive narrative that has underpinned bad poverty policy for so long is a maliciously clever ruse. But if what it means to be poor can be framed one way, then it can be framed in another, more truthful way, too. In fact, it is already starting. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has launched an initiative called “talking about poverty”,to which I will be contributing, that explicitly aims to examine how to change the conversation. It is incumbent on us to make that happen.