Food Deserts Exist. But Do They Matter?

America's healthy-eating disparities might have more to do with income and class than with geography.

Too many Americans are overweight and eat unhealthy food, a problem that falls disproportionately on poor and low-income people. Many have blamed the existence of “food deserts”—disadvantaged neighborhoods that are underserved by quality grocery stores, and where people’s nutritional options are limited to cheaper, high-calorie, and less-nutritious food.

But a new study by economists at New York University, Stanford University, and the University of Chicago adds more evidence to the argument that food deserts alone are not to blame for the eating habits of people in low-income neighborhoods. The biggest difference in what people eat comes not from where they live per se, but from deeper, more fundamental differences in income and, especially, in education and nutritional knowledge, which shape people’s eating habits and in turn impact their health.

To gauge the quality of food and nutrition by income groups and across different geographies, the study uses data from the Nielsen Homescan panel on purchases of groceries and packaged food-and-drink items between 2004 and 2015, which it then evaluates in terms of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Healthy Eating Index. It examines the gap between high- and low-income households: that is, those with annual incomes of $70,000 or more, and with incomes of less than $25,000 per year.

The study reinforces the notion that food deserts are disproportionately found in disadvantaged neighborhoods. It finds that more than half (55 percent) of all ZIP codes with a median income below $25,000 fit the definition of food deserts—that’s more than double the share of food-desert ZIP codes across the country as a whole (24 percent).

Furthermore, the study documents the disturbing extent of nutritional inequality in America. Across the board, high-income households benefit from better, more nutritious food. They buy and consume more of four very healthy types of foods: fiber, protein, fruit, and vegetables. They also consume less of two of four unhealthy ones: saturated fat and sugar. (Their consumption of sodium and cholesterol is basically the same as that of lower-income households.)

Indeed, the groceries of higher-income households are considerably healthier—in statistical terms, almost 0.3 standard deviations healthier—than those of low-income households, a gap that expanded substantially between 2004 and 2015. Overall, high-income households purchase one additional gram of fiber per 1,000 calories than low-income ones, which is associated with a 9.4 percent decrease in Type 2 diabetes. They also buy 3.5 fewer grams of sugar, which correlates with a 10 percent decrease in death rates from heart disease.

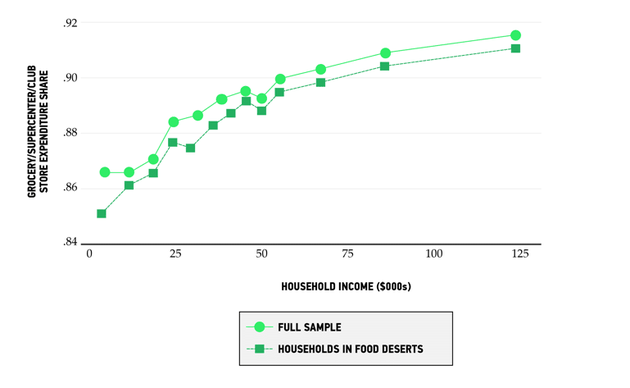

That said, there are some striking similarities in food consumption between high- and low-income households. They both mainly shop at grocery stores, no matter where they live. High-income households spend 91 percent of their grocery dollars at supermarkets. Low-income households spend just slightly less, at 87 percent.

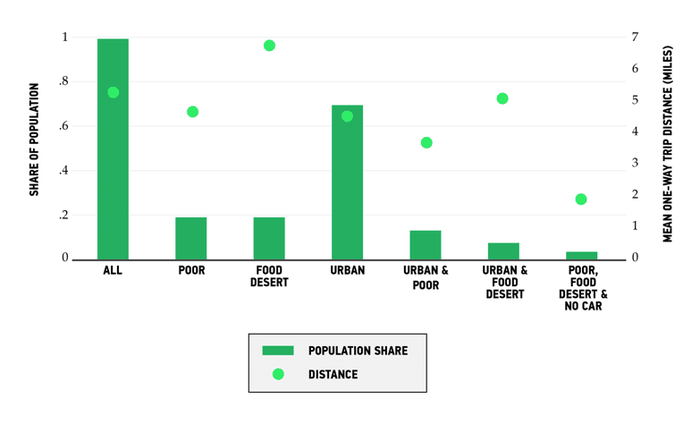

Also, both high- and low-income households, including those in food deserts, travel relatively similar distances to reach grocery stores, as the chart below shows. The average American travels roughly 5.5 miles to buy their groceries. Those in low-income households travel slightly less distance, an average of 4.8 miles. Americans who live in food deserts across the board travel farther, an average of 7 miles or so. But that includes those who live in rural areas. Those in urban food deserts travel a bit less than the overall average, while low-income households that live in urban food deserts and do not own a car—the group that the food-desert argument is mainly about—travel just 2 miles on average.

So what is the role of neighborhood location in American diets, and why do food deserts matter far less than the conventional wisdom says they do?

To get at this, the study cleverly tracks two things. First, it looks at what happens when new supermarkets open in less-advantaged neighborhoods, including food deserts. It turns out that the entry of new supermarkets has little impact on the eating habits of low-income households. Even when people in these low-income neighborhoods do buy groceries from the new supermarkets, they tend to buy products of the same low nutritional value.

Basically, new, closer-by supermarkets simply divert sales from older, farther-away supermarkets. As the authors of the study succinctly put it, “supermarket entry does not significantly change choice sets, and thus doesn’t affect healthy eating.” Overall, improving neighborhood access to better grocery stores is responsible for just 5 percent of the difference in the nutritional choices of both high- and low-income people.

Second, the study looks at what happens when low-income people move from neighborhoods served by lower-quality stores to ones with healthier offerings. Again, it finds little effect. Moving to a neighborhood where people have healthier eating habits has virtually no impact in the short term and a very small impact in the medium term, leading to just about a 3 percent improvement in the Healthy Eating Index scores of their grocery purchases.

Ultimately, the study finds little evidence to support the notion that food deserts are solely to blame for unhealthy eating. It concludes that the “evidence does not support the notion that eliminating food deserts would have material effects on nutritional inequality.”

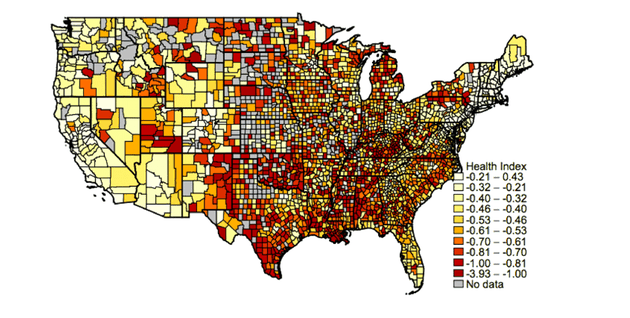

Instead of within cities, the biggest geographic differences in the way Americans eat occur across regions. The map below plots the geography of healthy versus unhealthy eating across America’s 3,500-plus counties. Dark red indicates a lower health index based on grocery purchases, while light yellow represents a higher health index. While there is some variation within cities and metro areas, by far the biggest and most obvious differences are across broad regions of the country. There is a large “unhealthy eating belt” across the Midwest and South, surrounded by healthier eating belts along the East Coast, West Coast, and Pacific Northwest.

Average Health Index of Store Purchases by County

Ultimately, the fundamental difference in America’s food and nutrition has more to do with class than location. More than 90 percent of the difference in Americans’ nutritional inequality is the product of socioeconomic class, according to the study. And it’s not just that higher-income Americans have more money to spend on food. In fact, the cost of healthy food is not as prohibitively high as people tend to think. While healthy food costs a little bit more than unhealthy food, most of that is driven by the cost of fresh produce. There is only a marginal price difference between other healthy versus unhealthy eating options. Furthermore, the price gap between healthy and unhealthy food is actually a little bit lower than average in many low-income neighborhoods, according to the study.

When it comes to food and nutrition, it’s not just that higher-income Americans have more money. They benefit even more from higher levels of education and better information about the benefits of healthier eating. Indeed, education accounts for roughly 20 percent of the association between income and healthy eating, according to the study, with an additional 7 percent coming from differences in information about nutrition.

The authors of the study suggest that equipping Americans with more knowledge and better information about healthy eating may be the better and more efficient path for policy. This seems a bit hopeful, though: Information on healthy eating is widely available, and calorie counts and ingredients are already listed on many, if not most, food items.

There are deeper reasons, again tied to class, that enable affluent and educated households to put this nutritional information to use. For one, they simply have more time and resources to devote to their health and well-being. Conversely, lower-income people may simply discount the health advantages of higher-quality food or see some of those foods, like kale or avocado toast, as smacking of urban elitism.

Whatever the case, America’s great nutritional divide reflects the fundamental class divisions of the country, mirroring the very same class divides seen in fitness, obesity, and overall health and well-being. It’s not food deserts per se, but this deeper fault line that is to blame for nutritional inequality.

This post appears courtesy of CityLab.