With the cold war settled into an almost comfortable stability, the 1970s were a golden age for spy novels in the US, with writers embracing the shadowy world of ambiguity that espionage fiction offered.

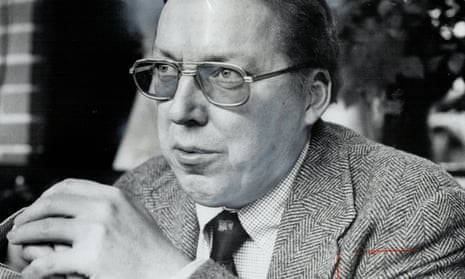

When Charles McCarry, who has died aged 88, published The Miernik Dossier in 1973 – introducing a CIA agent, Paul Christopher – his fellow author Eric Ambler called it “the most enthralling and intelligent piece of work” he had read in years.

McCarry’s next two Christopher novels, The Tears of Autumn (1974) and particularly The Secret Lovers (1977), were so impressive that it became common to bill him as “the American Le Carré”, though he never enjoyed the British writer’s bestselling success. McCarry himself would say that his main influence came not from John Le Carré, but from two earlier English novelists, Ambler and Somerset Maugham.

That he so quickly saw off the competing claims of, among others, Paul Henissart and Robert Littell, was down to McCarry’s grasp of the personal nature of spying, where betrayal lies at the heart of every action.

Like Le Carré, McCarry was part of the world of “honourable schoolboys”. He delineated as tellingly as Le Carré the specific, old-boy ethos which the modern CIA, like its predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services, had copied slavishly from the British. He understood that it was the very comfort of this system, with its assumption of loyalty from and to those within it, which made betrayal so facile.

McCarry’s first-hand knowledge came from 10 years working, under deep cover, for the CIA. He called those years “a time of extreme boredom”. There was little glamour in the actual tradecraft of spying. However, the experience allowed him to focus not only on the aims of the business, but the motivations of those in charge.

In his fourth novel, The Better Angels (1979), which formed the basis of the Sean Connery film Wrong Is Right (1982), McCarry noted that spies often had to collaborate with evil. “Evil was permanent and it was everywhere. What mattered was that it should be channelled, tricked into working for your own side.”

Although by the turn of the millennium all McCarry’s spy novels were out of print, his reputation was revived in part by the prescience of his vision. The Better Angels features Middle Eastern terrorists who use aeroplanes as bombs, probably the first novel to anticipate the methods of 9/11.

In Shelley’s Heart (1995), Christopher’s nephew Henry Hubbard masterminds a CIA fix of the 2000 US presidential election. When George W Bush was elevated to the presidency by the US supreme court after the disputed voting in Florida, the fact that George Bush Sr was once head of the CIA and that he, his own father and his son George W were all members of Skull and Bones, the ultimate “old boys” secret society at Yale, was a fortuitous coincidence.

McCarry, who once called lies “the facts of the left”, also satirised Bill Clinton’s presidency in Lucky Bastard (1998). His increasing relevance saw Overlook books bring his early fiction back into print, starting in 2005 with The Tears of Autumn; and he went on to write three well-received new novels in his 80s.

McCarry was born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and grew up in nearby Plainfield, where his father, Albert, ran the family farm and his mother, Madeline (nee Rees), an inveterate reader, amassed a library of 10,000 books and inculcated her son with a love of literature. He turned down a place at Harvard to enlist in the US army in 1948, and wrote for Stars and Stripes, the army newspaper, while based in Germany.

After a spell as editor of a paper in Lisbon, Ohio, where he met Nancy Neill, whom he married in 1953, he was writing speeches for President Dwight D Eisenhower when he was hired by Allen Dulles, the head of the CIA, to work for the agency. He continued to work as a journalist during his decade as a spy, even once, in 1965, interviewing Michael Caine about his role as the fictional British spy Harry Palmer.

He quit the CIA in 1967 to work full-time as a journalist and wrote a profile for Esquire magazine about the consumer crusader Ralph Nader which so pleased its subject that Nader invited McCarry to write his biography.

Citizen Nader (1972) was revealing, as McCarry grew fascinated by the ambiguities of the outwardly ascetic campaigner. He said: “I never approached a subject with more sympathy and left with less.” He would later co-write the memoirs of figures whom he left with more sympathy, Alexander Haig and Donald Regan.

After the success of The Miernik Dossier, McCarry intended to pursue, in non-fiction, his belief that John F Kennedy’s assassination had been a payback for the assassination of the Diem brothers in Vietnam. Instead, that idea turned into his most successful novel, The Tears of Autumn.

But after his fifth Christopher spy novel, The Last Supper (1983), McCarry changed tack with a generational epic, The Bride of the Wilderness (1988), which charted the history of the Christopher family in colonial and frontier days. This departure from the world of espionage may have contributed to the diminution of his loyal audience, and the mass market for epics of this kind had already been exhausted by John Jakes’s American Bicentennial series and its imitators.

McCarry soon brought Christopher back, explaining that he had been held for a decade in a Chinese prison, in a series of novels that traced the ultimate futility of the CIA’s enterprise, while telling the story of Christopher’s own life. In Second Sight (1991), Christopher discovers a daughter, raised among a Jewish Berber tribe, and in Old Boys (2004), he finds his German mother, thought murdered by the Nazi official Reinhard Heydrich.

Both books had a sub-text that treated the life of Jesus as an intelligence operation in disinformation by the Romans. Old Boys also contained a tongue-in-cheek satire of The Da Vinci Code. But there was nothing tongue-in-cheek about Christopher’s Ghosts (2007), a touching account of the agent’s childhood and first love in Berlin before the second world war.

In his ninth decade he published three further novels, the science-fiction Ark (2011), about an attempt to save the world from a coming apocalypse, and two tales of modern espionage, The Shanghai Factor (2013) and The Mulberry Bush (2015).

McCarry also did script doctoring, for the director John Frankenheimer, among others, as well as travel writing, particularly about the American south-west, and he edited From the Field (1997), a collection of articles from National Geographic magazine.

He is survived by Nancy, their four sons, Caleb, Nathan, William and John, five grandchildren and three great-grandsons.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion