Exploitation and abuse of workers is widespread across the UK economy, according to a new report, which finds that 17 sectors are high-risk for mistreatment ranging from wages theft to slavery.

Construction, recycling, nail bars and car washes were among the top sectors where the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA) said there was slavery. Agriculture, food packing, fishing, shellfish gathering, warehouse and distribution, garment manufacturing, taxi driving , retail, domestic work, and social care were also highlighted in the report.

The authority has new powers to investigate labour abuse in all sectors under the 2016 Immigration Act, and the report marks its first full year of work assessing the nature of the problem in the UK. The Gangmasters Licensing Authority had previously been limited to tackling abuse in the agriculture, food and shellfish sectors. “It’s not until now that we’ve had the ability to look, but it’s a case of the more you look, the more you find,” said Ian Waterfield, the GLAA operations director. The authority says measuring the prevalence of labour exploitation is difficult, but an increasing number of suspected cases are being reported.

Quick GuideModern slavery

Show

What is modern slavery?

About 150 years after most countries banned slavery – Brazil was the last to abolish its participation in the transatlantic slave trade, in 1888 – millions of men, women and children are still enslaved. Contemporary slavery takes many forms, from women forced into prostitution, to child slavery in agriculture supply chains or whole families working for nothing to pay off generational debts. Slavery thrives on every continent and in almost every country. Forced labour, people trafficking, debt bondage and child marriage are all forms of modern-day slavery that affect the world's most vulnerable people.

How many people are enslaved across the world?

The UN's International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates that about 21 million people are in forced labour at any point in time. The ILO says this estimate includes trafficking and other forms of modern slavery. They calculate that 90% of the 21 million are exploited by individuals or companies, while 10% are forced to work by the state, rebel military groups, or in prisons under conditions that violate ILO standards. Sexual exploitation accounts for 22% of slaves.

Where does slavery exist?

Slavery exists in one form or another in every country. Asia accounts for more than half of the ILO's 21 million estimate. In terms of percentage of population, central and south-east Europe has the highest prevalence of forced labour, followed by Africa, the Middle East, Asia Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean.

Who is profiting?

In 2005, the ILO estimated that illegal profits from forced labour amounted to more than $44bn. The UN's global initiative to fight trafficking says people trafficking is the third-largest global criminal industry (pdf) behind drugs and arms trafficking. The ILO estimates that people in forced labour lose at least $21bn each year in unpaid wages and recruitment fees. Slavery also exists within global supply chains, generating huge profits for those who control this industry in free labour.

Reported cases of slavery have increased 35% year on year, with the UK being one of the biggest destinations in Europe for trafficking of workers for labour exploitation. Debt bondage – where migrants often become indebted to recruitment agencies for travel or illegal work-finding fees – is common. Bogus self-employment contracts are also regularly used to disguise abuse, with intelligence suggesting this is a growing problem in sectors such as cleaning, construction and flower picking. Zero-hours contracts linked to abuses are highlighted in agriculture, construction, food packing and security services, despite many workers effectively being permanent staff.

The report also finds that organised crime groups are active in the labour market in many sectors. Most intelligence about victims of labour exploitation in the last 12 months has related to Romanian men in their 20s and 30s, while Romanian and British nationals are the most prevalent offender nationalities across all forms of modern slavery. Albanian organised crime is a significant factor in abuse in car washes.

Long shifts of 12-15 hours a day, sometimes seven days a week, wages below the legal minimum or not paid at all, and dangerous working and living environments were issues common to several sectors. But different sectors also had problems specific to them.

In nail bars the victims of trafficking for labour exploitation were mostly Vietnamese, with evidence that tax fraud and money laundering was also taking place.

In the agriculture sector, the GLAA found evidence of 15-hour days, sometimes seven days a week, with double shifts without proper breaks, illegally low pay, serious safety incidents going unreported, and very poor living conditions. Romanian and Bulgarian workers were currently most at risk in this sector. Criminal groups were reported to be trafficking foreign workers into the food processing sector, with licensed companies warning they were being undercut by unlicensed ones.

Wages in food service, hotels and catering could be as low as £10 per shift, with some employees working up to 15 hours a day, and sleeping on floors. In car washes, the GLAA found trafficking, 12-hour shifts seven days a week, wages below the legal minimum, dangerous accommodation on site, and exploitation of undocumented workers. Romanians made up the largest number of victims.

One-third of UK garment manufacturing is based in Leicester but up to 75% of workers in the city’s textile factories are said to be paid less than the legal minimum wage. The report says in some places more than half the workforce is made up of undocumented workers mainly doing night shifts. Victims of exploitation in this sector are predominantly Pakistani and Romanian.

Convoluted supply chains and subcontracting makes the UK construction sector, employing about 3 million workers, high-risk too. Its widespread use of self-employment contracts is directly linked to exploitation, according to the report. Gangmasters operating in the UK are also moving workers around internationally to meet shifting demand on building sites.

Waterfield said that now the authority had a clear intelligence picture, increasing enforcement was important. About 400 investigations by different bodies into modern slavery were active in October last year, but there are still few prosecutions, and convictions decreased by 6% between 2015 and 2017. The GLAA has opened 181 criminal investigations itself in the last year.

The chair of the parliamentary select committee for work, Frank Field, said both government and consumers needed to wake up to the scale of abuse. “This report sheds much needed light on some of the most rotten, grotesque and evil practices that afflict the bottom of our labour market. Slave labour is being used to prop up companies in large swaths of the economy. What is puzzling is how the government machinery and consumer backlash have yet fully to come to terms with this phenomenon.”

The NGO Focus on Labour Exploitation (Flex), which has recently researched the construction sector, said lack of resources was undermining government efforts on modern slavery. “Labour abuses put workers at a high risk of exploitation, with growing numbers in modern slavery – migrant and UK workers alike. We must urgently reverse the huge cuts to labour inspection in recent years,” its director, Caroline Robinson, said.

Protection money and 70-hour weeks

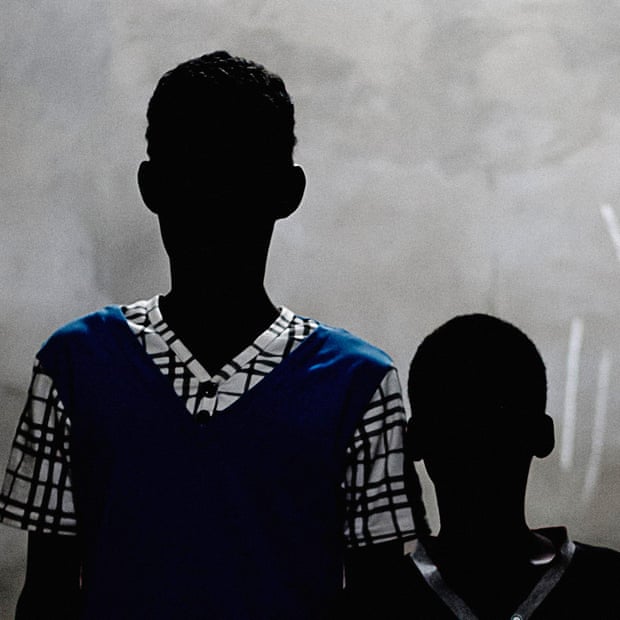

Dumitru Popescu, a 41-year old Romanian, is one of the thousands of migrant workers who make up half the labour force in London’s construction industry.

He had just finished a trial shift, working from 7.30am until 5.30pm without a break, demolishing a block of flats with hand tools because machine digging was prohibited. Compared with his previous job, this was good work and he wanted to keep it, so he was trying to calculate what he needed to pay the two Romanians who controlled employment on this site.

He said that giving a cut of your wages each week to supervisors as protection money was how the system worked. Newcomers were given the most back-breaking jobs; by paying his fellow Romanian overseers the right amount he would gradually move up the pecking order and stay safe on the same site. But how much that amount should be was not clear. He thought probably £50 a week but it was an anxious decision. Pay too little and you would be moved on and back to the bottom of the pile; too much and you would be subsidising them to stand around while you sweated, he explained.

Popescu (not his real name) has a contract with a large, high-profile recruitment agency which supplies thousands of workers for sites around Greater London. On paper, arrangements look fine and much better than queueing by the road in the places where contractors pick up day labour. He is paid £9.15 per hour – above the minimum wage – with deductions for tax and national insurance, but he said he did not really understand the deductions and thought they were too high, even before the protection money.

His first job on arrival in the UK had been as a casual worker in leading hotels where the hours were completely unpredictable, varying from 12 hours one day to four hours the next with no notice. He moved to construction, where the first company he worked for cheated him out of his pay so he cut his losses and moved on. He was taken on as a casual to work on a flat renovation but was never paid for most of his work, the owner claiming he had run into financial difficulties. With the agency he thinks he will be able to work seven days a week averaging 10 hours a day and so make ends meet. His wife is a qualified social worker back home but does hotel work now in between looking after their daughter. The three of them live in a single room in a four-bedroomed house he rents with three other families.

His experience is typical, according to Flex. This year, its survey of the labour force on building sites in the capital found that 36% of migrant workers reported not being paid for work done, a third reported verbal or physical abuse, half had no contract, and more than half had been made to work under dangerous conditions.