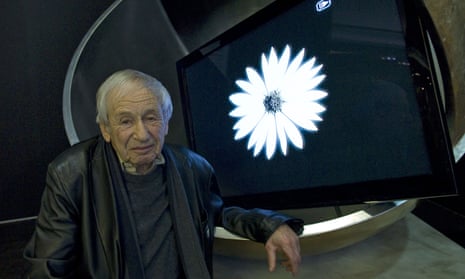

By instinct and inclination the designer Ralph Koltai, who has died aged 94, was a sculptor, but he chose the theatre as his workplace. His marvellous talent for the display of objects in space created many unforgettable and beautiful images; and the stage benefited for more than half a century from a talent distinct from that of his British contemporaries.

He also worked ceaselessly for a wider appreciation of the profession to which he belonged. As head of theatre design at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London (now Central Saint Martins, 1965-72), he was the valued mentor of many distinguished designers of later generations.

However, his life was not easy. He was a refugee from nazism and, despite his powers of assimilation, remained a lifelong exile. He was an independent artist; and, despite his shrewd understanding of its collaborative nature, he was not always fulfilled in the theatre.

His early work in the 1950s was with opera and ballet, and it was not until 1962 that he designed his first play, Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle, directed by William Gaskill, for the Royal Shakespeare Company. Over the next 20 years, Koltai’s work rate was prodigious and many of the designs by which he is best remembered were made.

In 1963, both Rolf Hochhuth’s The Representative and the Brecht-Weill opera The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny were clearly labours of love, grittily realised. For the RSC in the following year, he designed Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party, Samuel Beckett’s Endgame and Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta, his Malta a place of large, abstract, honeycombed blocks.

Next at Stratford, he worked with Clifford Williams on The Merchant of Venice and John Schlesinger on Timon of Athens. In those days, the RSC had their own rather circumscribed approach to designing Shakespeare and Koltai’s was resisted.

There was no resistance to his designs for Williams’s all-male production of As You Like It for the National Theatre at the Old Vic in 1967. His set was an evocation of nature in the new materials of the day: perforated plastic, plastic rods and plastic mirror, devoid of colour, but bathed in coloured light. He saw the Forest of Arden with such conviction that the audience saw it too. In 1969, his abstraction for Shaw’s Back to Methuselah at the National was more extreme, cosmological images conjuring the history of the race.

From this imagery developed the designs for the famous Ring cycle at English National Opera, conducted by Reginald Goodall and directed by Glen Byam Shaw and John Blatchley.

Conceived in the high noon of the American space programme, a cosmic account of the theft of the Rhinegold and the fall of the gods was played out on shards of broken slopes among dead and dying stars above a layer of black ash. The cycle emerged over four years from 1970; and the continuing flow of strongly abstract designs tempted the theatre world unfairly to pigeonhole Koltai.

For, at Covent Garden, before the Ring was finished, Koltai – working in a different manner – designed Peter Maxwell Davies’s Taverner, in which a struggle between the crown and the church was presented in cool tableaux of figures exposed to fickle fortune on his full-stage device that spoke of scales and a see-saw.

Dividing his time between opera and the spoken theatre, he worked unusually prolifically for a designer in Britain, with 10 shows in 1977 alone. In 1978, he designed Ibsen’s Brand for Christopher Morahan in the Olivier auditorium at the National Theatre, an epic set mastering that demanding space, and, a year later, at the other end of the scale, he designed Brecht’s Baal for David Jones at the RSC’s The Other Place, an evocative piece of work in a theatre so small that that the audience could not be deceived by distance.

Between 1982 and 1985, Koltai demonstrated his responsiveness to a director of stature in a collaboration with Terry Hands at the RSC on three plays, Much Ado About Nothing, Cyrano de Bergerac and Othello. If Much Ado and Othello were recognisably exercises in style, albeit dovetailed to the production, the designs for Cyrano were patiently evolved with the director in a poetic response to the needs of the piece and its human scale.

The designer spoke of Act V: “A convent garden. The autumn of Cyrano’s life: the crown of a tree shedding its leaves, hinting at stained glass, a rose window ...” In the theatre, the rose deepened to the red of spent blood, in the air and on the ground, a metaphor of consequences.

Koltai’s broad brush was not laid aside, however. In 1983, he designed Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s opera Die Soldaten in Lyon for Ken Russell. Asked for acting areas, he broke a woman’s body into three explicit chunks each 20ft across, urging them on his director, a famous apostle of outrage.

Six years later, asked by Jérôme Savary to bring Fritz Lang’s Metropolis to the stage, he cut up an Alfa Romeo gearbox to fill a model of the Piccadilly theatre. Realised in glass fibre, the pieces could only move supported by hovercraft technology. On Koltai went, fascinated by surfaces, reflections, translucencies, photo images and movement.

He spoke pertinently of the role of the stage designer: “Despite a production being a collaborative effort, the designer is a very lonely animal … For the designer to succeed requires a pronounced critical faculty, for he must also remain true to himself as a creative artist ... in the final analysis the decisions are his. It is entirely a matter of decisions. The quality and appropriateness of the design is dependent on these. Therein lies the difficulty – to recognise the right decision.”

Born in Berlin, the son of a Hungarian doctor, Alfred Koltai, and his German wife, Charlotte (nee Weinstein), Ralph attended a privileged school for Jewish children in the city. Amazingly he and the majority of his classmates escaped the Holocaust.

In 1939 he was granted a British entry visa and went to live in Scotland in conditions of hardship and in the face of hostility. Both his parents also left Germany, Alfred eventually settling in Cuba, and Charlotte taking work as a nurse in Epsom, Surrey.

In 1943, Ralph began training as a commercial artist at Epsom School of Art, before serving in the Royal Army Service Corps and the Intelligence Corps, latterly as a member of the British delegation to the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, and in “the London Cage”, working for the War Crimes Interrogation Unit, experiences that were to influence his designs for The Representative.

He studied at Central from 1948 until 1951: and began his career as a theatre designer before graduating, working on operas by Jacques Ibert and Darius Milhaud at the London Opera Club. Of his first 32 productions, four were ballets and the rest operas. While he designed familiar works by Mozart and Wagner, he was clearly identified with unusual artistic enterprise and worked on many rarities.

He returned to opera at the end of his career, at the age of 91, with a group of three operas for David Pountney and Welsh National Opera in 2016 on the theme of Figaro, consisting of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, Rossini’s The Barber of Seville and a new work, Figaro Gets a Divorce, with music by Elena Langer and a libretto by Pountney. Alongside it went Atomic Landscapes, an exhibition of metal collages at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama in Cardiff.

Koltai was appointed CBE in 1983, made a Royal Designer for Industry in 1984 and an honorary fellow of the London Institute in 1996, and won a number of national and international design awards.

In his house in France, he had a little polychrome wooden figure of his father dressed in the uniform of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, quizzical and stooped, as his son was to be after him. Ralph never lost the perspective granted by being a man of more than one country, nor did he entirely escape an isolation, conferred by transplantation and temperament. Although he had many professional partnerships, he never surrendered his imaginative independence, making of his isolation something splendid.

In 1956, he married the designer Annena Stubbs. They divorced in 1976. In 2008 he married Jane Alexander and she survives him.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion