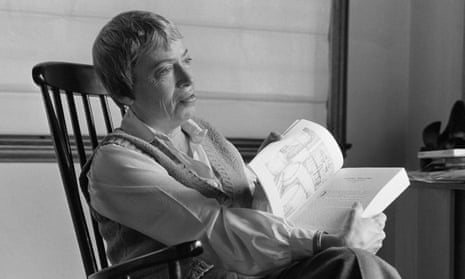

I only met Ursula K Le Guin the once, and her first words were a sly, “Oho, David, so this is an assignation!” She had a wicked smile and, as the Irish say, a face full of devilment. It was 2010, and we’d been left in a nondescript office of a bookshop in Portland, Oregon. I was in town to give a reading at the end of a US book tour. Quite how my American publicist had persuaded the unbiddable Ursula – who, doing the maths, was 80 – to give up a perfectly good evening for the sake of a passing British novelist, I have no idea; yet there she was.

Meeting your idols is a risky business – as Flaubert notes, the gold paint tends to come off on your fingers – but my 90 minutes chatting with Ursula only convinced me that the gold was genuine. She was not a glad sufferer of fools, it was clear, and you’d not want to cross her, but her graciousness that afternoon was unflagging. I gushed, of course. I told her how her Earthsea books had, as a boy, shown me how I wanted to spend my life – crafting worlds as real, as full and as irresistible as hers, or die trying. (Ursula observed that you could get away with princes and wizards in the 1960s and 70s, but by the 21st century they had become “cute”.) I told her how The Dispossessed and The Left Hand of Darkness struck me not merely as classily written novels where nuanced characters explore worlds both like and unlike ours, and survive not by force but by wit, cooperation and sacrifice. More than this, they dream into existence new ways for people to live. In old money, they are visions. (What could any author say to that except: “You’re welcome”?)

Our conversation turned to writing in general, our families and why cats are like dragons. Then, all too swiftly, our time was up and my event was starting downstairs. Ursula said goodbye and good luck in advance, though she stayed for my reading – a characteristically kind honour for a senior writer to bestow on a young upstart – before vanishing into the crowds.

While I never met Ursula face to face again, we stayed in occasional touch down the years. When Folio Books asked me to write an introduction to their beautiful edition of A Wizard of Earthsea I accepted on condition that Ursula approved the text. She answered a few fact-checking questions to help me. In one email, she described how the original Earthsea trilogy was written at night on the kitchen table, when her kids were asleep. The last time I emailed was to thank her for reviewing my novel The Bone Clocks. The gist of some mainstream reviews was: “Pretty good, but it could do with less fantasy.” Ursula’s was: “Pretty good, but needs more fantasy.” How gloriously true to form.

I’m glad that Ursula lived long enough to see her achievements and influence acknowledged by the literary establishment, albeit belatedly. She was a crafter of fierce, focused, fertile dreams. Her own story ended on Monday, but the story of Ursula’s fiction – the validation that The Left Hand of Darkness gave to a transgender friend growing up in Chicago, the inspiration that The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas gave to rapper RM of K-pop band BTS in Korea, the path that Earthsea illuminates for future writers, including this one – will continue to be written by future generations.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion