How much do you earn? There are few questions that British people find so excruciating – or rude. Walking around Bristol on a heaven-scented spring day, buttonholing random strangers about their personal finances, I sense most would prefer it if I were asking when they last masturbated, or passed stool, or voted Conservative.

“I’d say that’s a cheek!” says a gentleman in his 80s. But why? “I’m British, that’s why. My business is my business.”

I try a younger guy in athletic gear, performing stretches by a park bench. “If you ain’t paying me, I ain’t interested,” he says. A model neoliberal citizen.

I approach a couple of mothers in the park and cast a shadow over their picnic rug. One is a stay-at-home mum; the other is not. “It’s not something you want to talk about in front of your friends, is it, what you earn?” the latter says. “Some people are underpaid, some people are overpaid, life isn’t fair.” Her friend pointedly attends to her child. I apologise for ruining their lunch.

It’s awkward, isn’t it? The median annual income in the UK, according to the most recent Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, is £28,677 for full-time employees. Jeremy Corbyn’s last published tax return puts his income at £136,762; Theresa May’s was £117,350 but she hasn’t published one since she became prime minister; David Cameron never published a tax return, but he did publish his earnings in light of the Panama Papers scandal: £200,307 from salary and rent in 2014/15. José Mourinho is on a reported £15m at Manchester United and is apparently unhappy. Chris Evans makes more than £2.2m at the BBC. A nurse starts at £22,128. It ought to be one of the least personal things about us – a simple data point, one that’s not so hard to estimate, surely – and yet clearly it’s emotive. “I don’t think that’s a very nice conversation to have publicly at all,” as Kate Winslet told the BBC when pressed on the issue of gender pay disparities in Hollywood a couple of years ago. “It seems quite a strange thing to be discussing out in the open like that. I am a very lucky woman and I’m quite happy with how things are ticking along.”

The squeamishness is not limited to Britain – Donald Trump is in no rush to publish his tax returns – but it is acute here, and only made more so by the recent revelations about the gender pay gap. In Sweden, Norway and Finland, you can look up anyone’s salary online – a practice dating back to the 18th century. (Well, not the online bit.) And even with much more equal parental rights, they still have gender pay gaps similar to ours, about 15%-18%. In Massachusetts and other US states, less transparency is touted as the answer; employers aren’t allowed to ask what your previous salary was when you apply for a new job, to stop low pay following women and minorities throughout their career. And perhaps there’s something to be said for not knowing. A recently qualified teacher I know – whose salary I might estimate at about £24,000 – defended our reticence: “It’s a British thing which I am proud of – it seems crassly materialistic to discuss money in detail with acquaintances, or even friends.”

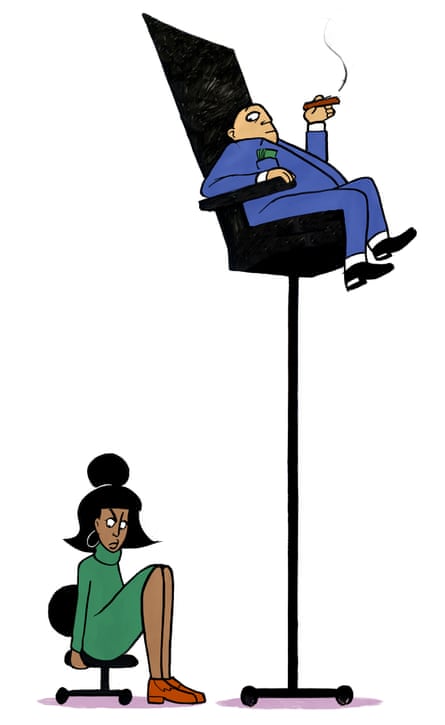

Still, we are increasingly being encouraged to drop our financial pants – at least in front of our immediate colleagues – as a means not only of addressing pay inequality, but also of changing the balance of power between employers and employees. I’ve been noticing friends open up a lot more about their finances, admitting they, too, spend an inordinate amount of time on moneysavingexpert.com, wondering: “How on earth does anyone else do it?” No wonder: the LSE recently calculated that British workers have seen the second worst wage growth in the OECD (after Greece), with wages falling 5% between 2007 and 2015 once adjusted for inflation. Income inequality is widening; society is fragmenting across class, age, gender and racial faultlines; envious, curious glances are cast.

And since last month, when 10,000 or so British companies were obliged to publish data on gender pay gaps under the Equalities Act, we’ve had even more numbers to pore over. About 78% of British companies pay men more than women. Men earn on average 18.4% more than women, or 9.7% if you go by the median hourly rate. The Guardian’s own gender pay gap is 12.1% in favour of men. I am freelance, so have been spared the tortured intra-office conversations, but when I last worked full-time (at the Evening Standard, which has a 5.8% pay gap in favour of women, to my surprise), it was a constant source of tension. Everyone knew that pay levels varied unpredictably and unfairly – and that the people who were good at getting raises were almost never the people who were good at their jobs. Still, while there was a bit of income solidarity among the younger (ie lower-paid) members of staff, hardly anyone else was willing to enter into an “I’ll show you mine” pact. It’s true there’s sometimes an advantage in being paid less – you’re less likely to be made redundant. But I couldn’t help noticing that when I eventually revealed my final salary to a female colleague after I’d left, she promptly left, too.

How much do I earn now that I’m freelance? Not enough to turn down a commission from the Guardian, but a lot more than the national average: let’s leave it there for now. As I ask these “vulgar” questions of friends, family members and random strangers, I detect two main reasons for squeamishness. One, you might earn too little and be ashamed. Two, you might earn too much and be ashamed. Revealing your salary might bring a twitch on either string, depending on who you’re talking to.

A fellow freelance writer on £26,000 confesses: “I do find it shameful to talk about because I feel like it’s not very much for someone who has had a lot of advantages in life.” At the other end of the income scale, there’s often a fear of being judged for having made certain compromises. “I wouldn’t share my salary because I’m quite embarrassed that I’m earning too much and still don’t feel it’s enough to live a comfortable London life,” says a friend who works in recruitment in the City. Another who classes herself as a “high earner” say she doesn’t want to be labelled a “corporate whore”.

“I like to be on equal terms with people irrespective of our salaries,” she says. “While I regularly get the extra round or pay for dinner for friends who might not have as much cash, I don’t like there to be an expectation that I will do those things.” There are further reasons, too. “It makes me feel self-conscious and embarrassed about my relatively modest living arrangements and asset accumulation given my high salary. And I don’t like knowing when people earn more than me. It leads me to question whether I’m sufficiently successful and leaves me feeling dissatisfied with my lot.”

The people most willing to share their figures, I find, are those who take a certain pride at having succeeded on their own terms. In 2012, Jack Monroe was on income support and in debt, with a food and fuel budget of less than £10 a week and a son to feed; now she is a successful food writer with a couple of bestselling cookbooks to her name and a company employing four members of staff. “Mine is the last salary to be paid at the end of each month,” she says. “I pay my staff well. I don’t want the people I work with to find themselves in difficult circumstances.” She pays herself £21,000 a year which, given she works about 50 hours a week, she estimates as about half what she pays her cleaner (£14 an hour). “I probably don’t get paid as much as I should, but that’s a hit I’m prepared to take as I’m used to living on not much money. It’s a real skill being financially resilient and keeping your head.”

My old university friend Simon, who has cerebral palsy, tells me he earns “closer to £40,000 than £50,000” as a policy research manager. “Very few people ever ask me this question as most of the occupants of our village who go down the pub seem to be either scientists for biopharma or financial masters of the universe which makes my salary seem puny,” he says. “Nonetheless, in terms of providing the nice things my family need, I feel well paid, and in terms of what my father gets paid – all I have ever really aspired to – I am doing OK as well. For me, it is also about being a disabled person – my quality of life is far better than many other people in my position typically expect and I feel profoundly lucky.”

Still, a headline figure can be misleading. You might earn £10,000 working for a charity because you’re a saint; you might also be married to a management consultant who makes six figures by laying other people off. You might turn down that slightly compromising commission because you have impeccable ethical credentials; you might also have a trust fund. Also: which number do you choose? It’s customary to cite pre-tax income on job adverts in the UK, but it’s not in France and many other European countries – which immediately changes your relationship to that figure. If you’re self-employed, do you cite gross income (ie all the money you earned in a year), net profit (ie all that minus expenses) or post-tax income (ie all that minus the amount you pay in tax)? How do assets come into it?

And what about benefits, tiny amounts, really, but which often incite just as much envy and resentment as, say, the £3.4m home secretary Sajid Javid is reckoned to have earned when he was at Deutsche Bank? It gets complicated. The first person I encounter in Bristol is Kirsten, 49, walking with a crutch with Snoop, her staffie cross. “We saved each other,” she says. Following failed surgery on a degenerative spinal condition, she lives on disability benefit and volunteers at a local hospital for the chronic pain management programme. “I don’t really know how much I get… I mean, I sort of know. But I’d rather not say.”

She’s used to difficult conversations about pay. Before her operation, she spent most of her career administering mental health services for the local authority (“But that was cut due to funding reasons”) and went on to work in human resources for a small firm that recruited healthcare professionals. “It was so hard to make everything fair,” she says. “I’d be fighting for individuals who’d been on minimum wage for a long time. There was a bit of hypocrisy going on in management, them all getting bonuses and the people at the bottom being on minimum wage.” Her current benefits are OK: “But it’s been a hard slog to fight for them.”

People on lower wages – and especially on minimum wage – are generally fine with telling me. I catch Theresa, 54, a contract cleaner, just as she finishes her shift at a supermarket. “I was fortunate when I had my family because my husband had his own business, so I was ‘kept’ for a while. But then my husband got ill and was unable to continue with that. The benefits weren’t enough. He was lucky to find this cleaning job, but he found it a struggle with his medical condition – he lives on painkillers – so we were able to job-share. When he’s struggling I step up the pace and the company’s happy. And because we do a good job, we get sent here, there and everywhere as overtime.” The ability to share hours and fuel costs with her husband is a bonus. “But what goes in comes out.” After rent, council tax, bills and so on, she’s left with “pennies”.

But she says she’s lucky. She likes the variety of locations, and the hours (approximately 5am-1pm) mean she can look after her grandchildren after school, so that her children can go to work. “My daughter-in-law starts work at five, finishes at one, comes home, hands my son the keys, and off he goes until 11 at night. If they do it that way, they don’t have to pay for childminders. And still at the end of the day, they haven’t got anything for what I call the little luxuries – you know? And that makes me quite cross.”

Mickey, 58, is philosophical about the £23,000 he is paid as a park keeper by the council. “It’s not bad – but I could be earning more,” he reflects. “I used to have my own company and run my own contract here, but then the council took over and employed me.” He hasn’t had a pay rise for six years, so in effect his pay has gone down. But as a public sector employee, he can at least look up what his bosses are earning. According to the Bristol city council website, its highest paid positions are strategic directors (on £136,000); the salary ratio of highest-paid to lowest-paid employees is about 10:1. (Private companies will soon be obliged to publish this data, too.) However, the highest-paid roles are being replaced by new, even higher-paid roles: executive director (£135,000-£165,000), level two director (£94,000-£120,000) and level one director (£85,000-£105,000).

But Mickey is philosophical. “They do a job,” he says. “They get paid the going rate. There are no tensions.” Indeed, he reckons his job is more enjoyable than theirs. “I grew up round here. My dad worked here. This is special, the best place in Bristol. I’d do this for no money.” Let’s hope no strategic directors read this.

I notice Ed, 44, sitting at a table by the park cafe, tapping at his laptop in aviator shades. “I can tell you what I earn, but it’s weird – I’m not a normal 9-5 type person,” he says. “It’s nothing at the moment.” He recently returned from Austin, Texas, where he launched a craft cider business that paid him an annual salary of about $85,000 (£62,500); he sold most of his shares for a seven-figure sum and is currently working out what to do next. In the meantime, that “nothing” includes an annual dividend of about £25,000 a year from a cider bar he owns in Bristol.

“I’m in an exceedingly lucky position,” he says. “I come from a pretty poor background. None of my old friends is a particularly high flyer – I’m kind of the friend that my mates take the piss out of for being rich. People tease me about what I’m going to do with the money.”

He has always been of a “tax the rich” mindset, but now he has to adhere to that himself. “One of the things I hate is that when you go to see any accountant, the assumption is you want to pay the minimum amount of tax. That agenda is unhealthy.” To his surprise, his US accountant recently told him he was exempt from paying a significant amount of tax he thought was due on the capital gains in his business, owing to a piece of post-financial crash-era legislation. So now he’s figuring out what to do with it. “I’d like to do something with a bit more social worth than just getting people drunk,” he says. “Maybe something political.”

I speak to a couple of retirees whose dogs are entangled: David, 88, and Sue, 73. “We’ve just met,” David says. “She’s from Yorkshire, I’m a Bristol native.”

“I’ve lived in Bristol 27 years, thank you very much.”

“You’re still a newcomer.”

David spent most of his career as a schoolteacher and a local government officer before that; when I ask how much he earns, he says “nothing”, besides his state pension and his teacher’s pension. How much is that? “Aha!” he says. “I’m not telling you because you can find out.”

“The same with me,” Sue adds. “It would be easy for you to find out. My state pension is the very basic state pension and it’s topped up by the very basic pension credit.” (She eventually discloses that it’s £120 a week, plus £101 top-up.)

David considers reticence to be a British trait. Sue isn’t convinced. It depends where in Britain you’re from and when you were born. “I come from a mining village near Wakefield where everybody knew everybody’s business, so attitudes were completely different,” she says. “People were careful with money because there wasn’t a lot of it to go round. That’s the difference between then and now. There is too much of an attitude now of, ‘I want it, I’ll go out and get it.’ Then, if you couldn’t afford it, you didn’t have it.”

“How much do you earn then?” David asks me.

None of your… oh, OK. My gross income was £70,242 on my last tax return, which would put me in the top 5% of British earners. I find that at once reassuring and awkward. Once I lopped off expenses, my income was £49,250. And once I’d done my bit, chipping in for the NHS, a few military operations, Jacob Rees-Mogg’s pension, etc, I was left with £32,165. Which makes me think, hmm, maybe I should start a craft cider business.

I still find these numbers a little limiting. How do you factor in security, for example? I have no pension, no sick pay or holiday, no idea what I will be doing next month, and recently lost my one regular source of income, so my bank balance fluctuates wildly. Or joint income? My wife, also a freelance writer, earns much less, so it’s ended up being me who pays all the bills, childcare, rent and so on. Or hours worked? Usually 60 a week? Journalism is not a growth industry. With a rough average of 40p a word, I must publish about 175,000 words a year, about two novels’ worth, to sustain it… And yet, I’m white and male, I’m not scraping sewers or toileting the elderly, and I feel the need to provide hundreds of extra words to justify my privilege (also: I’m paid by the word). I suppose my main worry is not what I earn now so much as what I’ll earn in the future. Is the industry sustainable? What will I do when I’m old? How does anyone else manage? The wider narrative since 2008 has been one of decline: work more, expect less, hope you get lucky. Short of envious of my fellow citizens, I’m simply impressed that anyone can make it work.

I approach a man who’s quietly drinking a beer while looking after his baby daughter. He’s a stay-at-home dad for three days of the week and earns £15,000 from a couple of days lecturing at Bristol University. His wife works at Airbus and is the main breadwinner. “We had lots of clear conversations about how best to make it all work, economically and emotionally – and I’m certainly not resentful because we’re in a happy position where one of us can spend time with the children,” he says. “I think the conversation has matured. People recognise that to earn a stupid amount of money, you have to make sacrifices elsewhere.”

Does he think Swedish-style salary transparency would help matters here? He sighs. “It would require such a change of mindset. Post-Brexit, I’ve lost a bit of faith in humanity, to be honest. As things roll on, that concept that we’re going through progress… you kind of think, huh. Maybe we can regress sometimes, too?”

Three Hare Krishnas on a hill are playing a harmonium and chanting mantras in harmony. When I tell them I am going around asking people how much they earn, they all laugh.

“That’s such a boring question!” says Jahnava, 45. “I thought it was going to be something juicy.” She works for a charity called Coracle, which provides her a salary of about £5,000. Woah, that’s not much, I say. “I rely on the Lord.” You would say that. What about food, shelter? “It’s provided by the charity.”

Her friend Ellis, 22, has long blond hair and a shirt with lobsters and bananas on it. “I don’t know how much I earn – I don’t have a job right now,” he says. “I’m looking to get a portering job in the hospital, which would be about 18 grand, I think.” How does he support himself in the meantime? “I don’t know.” He laughs. “Jobseeker’s allowance. And lovely people around me. My grandparents give me a little bit of cash sometimes.”

I mention that most people find these conversations difficult.

“Maybe British people are too much in their minds?” Jahnava says. “At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter how much money you have to live. If you have food, shelter and your health, there’s nothing to stop you from being completely content. I was watching this video of a famous person being followed around by the paparazzi, and I realised how these people have sacrificed all of their privacy and freedom for their fame and wealth. I wouldn’t give that up for any price.”

This article was amended on 21 May 2018 to omit some personal information.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion