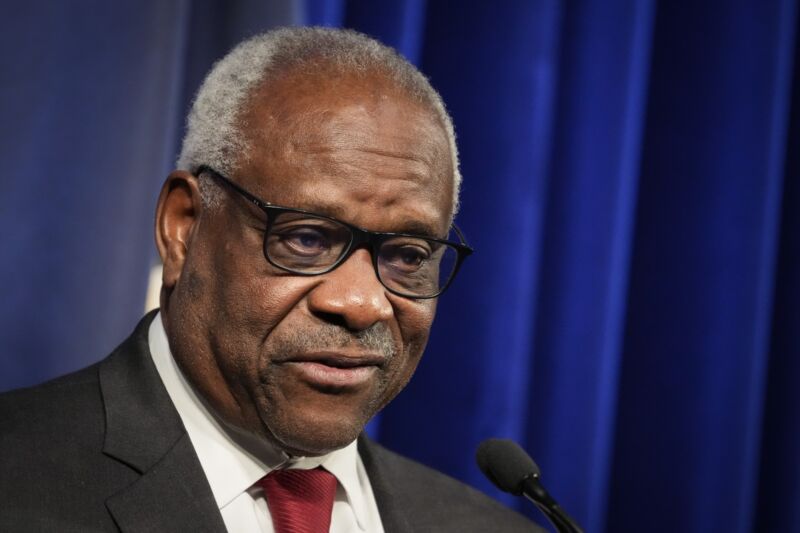

With tech groups asking the US Supreme Court to block the new Texas law against social media "censorship," the state's defense relies in part on an opinion issued last year by Justice Clarence Thomas in a case involving Donald Trump and Twitter.

Thomas' opinion, as we wrote at the time, criticized the Section 230 legal protections given to online platforms' moderation decisions and argued that free-speech law shouldn't necessarily prevent lawmakers from regulating those platforms as common carriers.

"In many ways, digital platforms that hold themselves out to the public resemble traditional common carriers," Thomas wrote. "Though digital instead of physical, they are at bottom communications networks, and they 'carry' information from one user to another. A traditional telephone company laid physical wires to create a network connecting people. Digital platforms lay information infrastructure that can be controlled in much the same way." The similarity between online platforms and common carriers "is even clearer for digital platforms that have dominant market share," Thomas also wrote.

The April 2021 opinion had no immediate practical impact. It was a concurring opinion in a case in which the Supreme Court vacated a 2019 appeals court ruling that said then-President Donald Trump violated the First Amendment by blocking people on Twitter. The court declared the case "moot" because Trump was no longer president.

But Thomas' opinion raised eyebrows at the time, and it was cited yesterday in the Texas response to Big Tech's attempt to block a state law that prohibits social media companies from moderating content based on a user's "viewpoint." With help from the Thomas opinion, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton argued that Texas can regulate social media platforms as common carriers.

“Texas law declares the platforms are common carriers”

"Even if the Hosting Rule implicated the platforms' First Amendment rights in some way, the Attorney General is still likely to prevail because Texas law declares the platforms are common carriers. The State may therefore properly limit the platforms' ability to discriminate among their customers," Paxton argued.

Pointing to historical examples of telegraphs, telephones, and cable operators, Paxton told the Supreme Court that "Texas has as compelling an interest in preserving its residents' ability to communicate and receive information on the platforms as States had regarding these previous generations of communications technology."

There is "little doubt that the platforms resemble historical communications-provider common carriers sufficiently to justify the continued application of these principles, as Justice Thomas has explained," Paxton wrote, referring to Thomas' concurring opinion in the Trump case. On the question of "whether the platforms possess market power," Paxton cited Thomas again while writing that "[s]everal jurists have suggested that they believe the platforms wield such power." Paxton also quoted Thomas' statement that the social networks have become "dominant digital platforms."

Texas also cited Thomas' concurring opinion earlier in the litigation when filing briefs in lower courts.

Texas, Florida laws blocked on First Amendment grounds

Despite Thomas' views, courts have ruled that the First Amendment does not prohibit websites from restricting speech on their platforms. Even after Thomas issued his opinion, the Texas law and a similar one in Florida were blocked by federal judges who ruled that the laws violate social media companies' First Amendment right to moderate user content. Additionally, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act explicitly says online platforms shall not be held liable for restricting access to content the platforms consider objectionable, "whether or not such material is constitutionally protected."

Although the Texas law was originally blocked by a US District Court judge on First Amendment grounds, it was revived last week by the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The Fifth Circuit judges issued a one-sentence order that did not explain their reasons for staying the preliminary injunction. Big Tech groups then asked the Supreme Court to reinstate the injunction to prevent Texas from enforcing the law while litigation continues.

Florida's law remains blocked, and the state is keenly interested in the outcome of the Texas battle. Florida yesterday filed a Supreme Court brief supporting Texas, and the Florida brief was co-signed by 11 other states: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, and South Carolina.

"Amici states have a strong interest in defending the regulatory authority of sovereign states in this area," the Florida brief said. "Indeed, many states have enacted, or are considering, laws that resemble Texas's and Florida's laws, and believe that the Fifth Circuit was correct to stay the district court's injunction pending appeal."

The Texas law applies to social media platforms with "more than 50 million active users in the United States in a calendar month." It says that a "social media platform may not censor a user" based on the user's "viewpoint" and defines "censor" as "block, ban, remove, deplatform, demonetize, de-boost, restrict, deny equal access or visibility to, or otherwise discriminate against expression." Under the law, users or the Texas attorney general can sue platforms that violate the ban.

reader comments

536