He had been dead for over two years, but he still had a magic touch with readers.

When best-selling author C. David Heymann's latest (and last) book, Joe and Marilyn: Legends in Love, came out in July, it received the kind of reviews most authors would kill for. The Columbus Dispatch called it an "engrossing portrait." The Christian Science Monitor and the New York Post raved. Kirkus Reviews said it was "a well-researched story" revealing the "profoundly unethical behavior of the medical and mental health professionals who dealt with [Monroe]." The popular Canadian magazine Maclean's praised Heymann's research, finding "his sources credible."

The publisher, a subsidiary of media behemoth CBS, saysJoe and Marilyn tells "the riveting true story" of the lusty, tempestuous and brief marriage between the Yankees slugger and the iconic actress. In this and his previous 10 books, Heymann served up intimate details no other celebrity biographer could match. It was often titillating and sometimes shocking stuff. In Joe and Marilyn, Heymann wrote that DiMaggio beat Monroe, wiretapped her home and stalked her by skulking around in disguises, wearing a fake beard and for hours holding up a copy of The New York Times so no one would notice him in the lobby of the Waldorf Astoria hotel.

In May 2012, Heymann fell dead in the lobby of his New York City apartment building, but that presented no problem for his publisher, according to Emily Bestler, who edited his last four books. She told Newsweek during a phone conversation in July that Heymann was "a true professional" who "finished the book before he died." Still, Bestler said, she paid to have the book thoroughly fact-checked just to make sure all was in order. Nothing troubling turned up, she told me, not even a misspelled name.

Bestler's mood changed when I told her I wanted to discuss numerous fabrications Newsweek had uncovered in Joe and Marilyn. She cut me off in mid-sentence, shouting that such questions were improper because she had thought I was calling only to ask about the marketing of a book by a dead author. She then declared that "this is getting ugly" and hung up.

When Paul Olewski, a spokesman for CBS's Simon and Schuster publishing division, called me back, he was very polite but said he did not want to hear what Newsweek had found about any of the books by Heymann CBS had published, and that Bestler would not agree to an interview with Newsweek.

It's too bad CBS didn't want to hear more, because all the celebrity bios Heymann wrote for them and other publishers—dealing with JFK, Bobby Kennedy, Jackie Kennedy Onassis, Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe—are riddled with errors and fabrications. An exhaustive cataloging of those mistakes would fill a book, so a sampling from his long career will have to suffice.

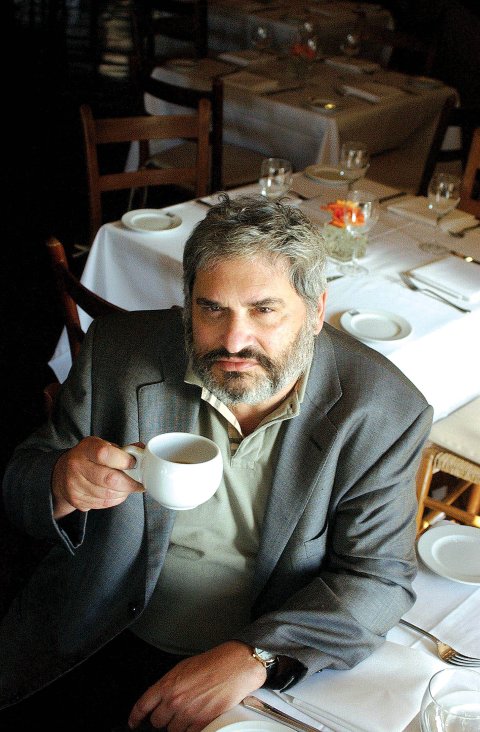

Cooking the Books

His given name was Clemens Claude Oscar Heymann. He was a large man, known for chomping on cigars, boasting that he liked to write in the nude (wearing socks) and talking up women about his kinky sexual predilections—just the kind of biographical details that would play so well in his books. He earned a degree in hotel management from Cornell, a master's in fine arts from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and did work on a doctorate in English literature at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

He then embarked on what he no doubt hoped would be a long, respectable career as a literary biographer. His first nonfiction book, Ezra Pound, The Last Rower: A Political Profile, was published by Viking Adult in 1976. The reviews were pretty good, but sales were pretty poor, and Heymann got cuffed by the respected scholar Hugh Kenner, who revealed that an interview Heymann claimed he had conducted with Pound had been done by someone else and had appeared in an obscure Venetian publication. Heymann denied any impropriety and said Kenner was motivated by spite because he had once criticized Kenner in a review.

Heymann's second book,American Aristocracy: The Lives and Times of James Russell, Amy and Robert Lowell (1980), got savaged by reviewers. Kirkus said it was "studded with outrageous bits of gaucherie, bad taste, and ignorance," and another, strangely prescient reviewer said, "Written with neither grace nor insight, and in information largely derivative and too often in error, the book is kin to those tawdry, revelatory biographies that make for today's best-selling, non-fiction list."

American Aristocracy did claim one literary prize: The Village Voice's "Most Mistakes Medallion" in 1980.

Heymann learned his lesson about the art and craft of writing a biography, but not the one you might expect. Speaking of this experience, he told The New York Observer in 1999 that he realized one should "never write a book about a poet if you want to sell books."

That was one mistake he never made again.

Recanting and Kantor

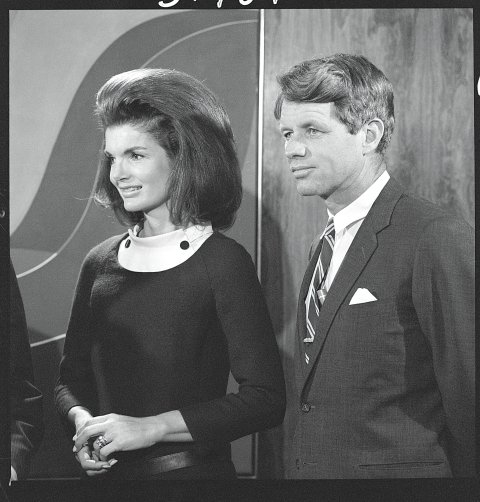

Heymann switched from poets to celebrities, scored big in 1983 with Poor Little Rich Girl: The Life and Legend of Barbara Hutton and then ran off a string of best-sellers that included A Woman Named Jackie (1989), his depiction of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis's life; Liz: An Intimate Biography of Elizabeth Taylor (1995); RFK: A Candid Biography of Robert F. Kennedy (1998); and Bobby and Jackie: A Love Story (2009).

For 30 years, I watched with astonishment and then bemusement as major publishers gave Heymann big advances, and respected media outlets—The New Yorker, The New York Times, People, Vanity Fair, USA Today and NPR—praised and promoted his books. I had exposed his first celebrity bio as a fraud on the front page of the Los Angeles Times back in 1983, and I knew his methods hadn't changed over the years.

Random House gave him a $70,000 advance for Poor Little Rich Girl, big money back then for a little-known writer. Heymann said the book would be based on diary-like notebooks Hutton kept and extensive interviews Heymann conducted with the dime store heiress about her seven husbands and rapidly diminishing fortune—picture a Paris Hilton who dies a near-penniless recluse.

As promised, the book was salacious and gossipy. As might have been predicted, it was also riddled with errors, exaggerations and shameless fabrications.

My investigation of Heymann's work began the day Random House withdrew the best-seller, vowing to pulp as many of the 58,000 printed copies as it could recover. That drastic action came after Mickey Rudin, a top Hollywood entertainment lawyer, threatened litigation. Rudin represented Dr. Edward A. Kantor, whom Heymann accused of prescribing excessive drugs for Hutton as far back as 1943. Kantor was just 14 years old in 1943.

The book spun out lurid tales that collapsed with just a phone call or two. Without much effort, I found nine people named in the book or known to have been involved in events mentioned in the book, including the legendary actor Cary Grant, who was once married to Hutton. All disputed Heymann's account. One example: Heymann claimed that in 1965 Hutton was flown from Mexico to San Francisco Presbyterian Hospital, where Dr. Lawrence Nash treated her with "a nutritious soybean protein mixture" and warm Coca-Cola to wean her off alcohol. The hospital told me that no doctor by that name had ever worked there and that no such treatment would have been allowed.

When I got Heymann (and his lawyer) on the phone, he insisted he had interviewed Hutton many times but had no tape recordings, only handwritten notes. He could not describe the hotel suite where he said he repeatedly interviewed her. He told me he had flown out to Los Angeles from New York many times for these interviews and stayed in hotels, so I asked for his plane tickets and lodging receipts, which would be a paper trail supporting his claim. "Why would I have those?" Heymann asked. I explained that without receipts he could not deduct those expenses on his tax return.

I then asked him about a group of people in his book who were also mentioned in an earlier book by Philip Van Rensselaer, a sometimes companion of Hutton. Van Rensselaer had already confessed to me that he had invented these people after his publisher complained that his book needed to be livened up or it would not sell. In his book, Van Rensselaer attributed the names to a 1920s New York Sun newspaper article, which he also made up.

When I laid all this out for Heymann, he insisted that Van Rensselaer was lying about lying and that these people and the Sun story were real. Heymann said he had obtained a copy of that article from a Staten Island warehouse that had a complete collection of old Suns. When I asked for a photocopy of the article, Heymann told me he had only taken notes during his many visits to the warehouse, because the old newsprint was too fragile to put on a copy machine.

I told Heymann that this was the first thing he had said in our interview that could be independently verified and that I would immediately jump on a red-eye from L.A. to New York, pick him up the next morning and drive us to that warehouse. Heymann's response: He wouldn't know how to find it again.

At that point, his lawyer told him not to say another word and declared the interview over.

A few weeks later, Heymann found a new publisher for Poor Little Rich Girl. He rewrote huge chunks of the book, and the work paid off. In addition to the money he got from his new publisher, Lyle Stuart, he cashed a reported $100,000 check for the dramatic rights to the book, which became an NBC television movie that won three prime-time Emmys and a Golden Globe.

Jackie O, No!

Heymann claimed he didn't escape the Random House fiasco unscathed. He later said he attempted suicide (a dozen Valium and half a bottle of scotch) in the aftermath of his book being pulled off shelves and pulped, and he moved to Israel for a few years. (He later boasted he worked for Mossad, the Israeli spy agency, but there is no independent confirmation of that.) But he wasn't through with books. He aimed much higher with his new one, writing about the life and loves of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, one of the most famous and fascinating women in the world.

In A Woman Named Jackie and later in Bobby and Jackie, Heymann quoted the savvy Democratic Party strategist Larry O'Brien spilling his guts about the Kennedys, including a supposed incident in a Nebraska diner where, "four of the roughest, toughest-looking hombres I'd ever seen…were looking for a fight" with O'Brien and Bobby Kennedy. In a 1989 Miami Herald interview, O'Brien denied making various comments Heymann attributed to him, and pointed out that his own memoir contradicted many of the things attributed to him by Heymann.

Both O'Brien's namesake son and Michael Gillette, the Texas historian who spent weeks recording oral history interviews with O'Brien, found the quotes unbelievable. "Even when he was off-tape—and O'Brien and I spent a lot of time at dinner in New York when he would let his hair down—this is not the sort of thing he would have ever said."

Supporting Gillette's claim is the fact that the quotes attributed to O'Brien bear no relationship to his well-documented speaking style, which was formal and specific, as opposed to the crass vulgate Heymann put in quote marks. Indeed, all of Heymann's books feature long quotes from people that evidence a consistent speaking style. In other words, they read as though they were all said—or written—by the same person.

Heymann tells another wild story in A Woman Named Jackie. A teenage Irish girl, who had just been released from a Dublin mental hospital and "had a 14-inch butcher knife in her shoulder bag," was brought into the Oval Office at JFK's insistence. Heymann attributed the story to his interview with Kennedy confidant Lem Billings, who died in 1981, years before Heymann started working on the book.

No matter. A Woman Named Jackie was No. 1 on the New York Times best-seller list for five weeks, and People magazine named it the "best book" of 1989. It sold more than a million copies in hardback and was turned into a 1991 NBC miniseries.

Heymann followed that with Liz: An Intimate Biography of Elizabeth Taylor (1995). He claimed he had secured Taylor's cooperation for the book, in which he wrote that she was beaten by two of her husbands, popped pills like candy and had a fling with Frank Sinatra. Her lawyer filed a lawsuit to block the NBC miniseries based on the book, declaring that none of that was true and that, contrary to Heymann's claims of cooperation, Taylor had never spoken to Heymann or anyone working for him. A judge denied her request to block the broadcast, saying the proper approach was to sue after it aired.

Heymann went back to the Kennedys for RFK: A Candid Biography of Robert F. Kennedy (1998) and scored again. While Heymann at times emphasized that he taped interviews, he often refused to let those he interviewed make their own tapes. In 1988, Kristi Witker, the longtime WPIX news anchor in New York, gave Heymann some prosaic photographs for RFK and granted him an interview, which he refused to let her tape. She said she told Heymann that soon after she graduated from college, American Heritage sent her, a 21-year-old cub reporter with an affinity for miniskirts, on the 1968 campaign trail with Bobby Kennedy, who was then vying for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination.

When RFK came out, Witker was besieged by reporters who had read Heymann's claim that she had been Bobby Kennedy's "last great romance." An exasperated Witker told me, "Of course reporters believed it, because it was in a book."

She was outraged. "Why did you make up these awful quotes," she asked Heymann, who, she says, replied that he did it because "everything you said was too banal."

Witker's lawyer threatened to sue. In a letter to his publisher's lawyer, Heymann took a contemptuous tone. "I told Kristi to send me a better way of putting it if she could find one. Readers will know what it means, and anyway…there were so many goddamn women in RFK's life, nobody'll really care. What's one more or less? It even begins to bore me."

Heymann may have found this line of inquiry boring, but he directed the State University of New York at Stony Brook, where he'd bestowed his archive, to seal the part of the archive dealing with Witker.

The Sexiest Bisexual Alive

Heymann invented so many people and events for his books that he wasn't able to keep them straight. In American Legacy he wrote of "Susan Sklover, a graduate student at Brown during JFK Jr.'s years at the university"—1979 to 1983— who talked about the women JFK Jr. supposedly dated while he was there.

Two years later, in Bobby and Jackie: A Love Story, Heymann described a Susan Sklover who worked as a White House masseuse while JFK was president, a job title that was a cover for her real job: prostitute. Heymann wrote that Sklover quit after six weeks and that Pierre Salinger, JFK's press secretary, sent her on her way with a $5,000 check—which would have created a paper trail—and an ominous warning to keep quiet. Heymann also describes President Kennedy's evaluation of Sklover's technique—"ordinary lover"—without any indication of how Heymann could have known this.

Heymann wrote that Sklover's name was kept out of Secret Service logbooks, a variation of an assertion in his other books to explain his reliance on people for whom no records exist.

Brown University, in an email, said it has no record of any student named Susan Sklover.

An exhaustive search of public records turned up two women named Susan Sklover, who are aware of each other, but know no one else with that name. Both said they never spoke to Heymann or any researcher. Neither attended Brown, knew JFK Jr. or worked at the White House. The women were born in 1954 and 1960, which meant they were both children during the Kennedy administration.

Heymann's Bobby and Jackie: A Love Story, which Bestler also edited, has many anecdotes that are incredible but hardly credible. The astounding claim, central to that book, is that Bobby and Jackie were in love and became lovers soon after JFK was assassinated. Another intriguing bit of pillow talk was that Bobby Kennedy also had an affair with Russian ballet star Rudolf Nureyev, who boasted several times that he was "the sexiest man alive."

Who told Heymann this? He said in the book that his source was journalist Jack Newfield, who died in 2004. Yet back in 1994, when Heymann first made those claim in his revised A Woman Named Jackie, Newfield wrote a column in the New York Post denouncing Heymann for "libeling the dead" with this claim. Whether Heymann was getting revenge on the late journalist or simply could not keep his stories straight is not clear.

Heymann also wrote in that book about a time Bobby Kennedy abandoned a picnic in Virginia and hopped onto a motorcycle with a woman; Heymann says the two were soon observed, "copulating in public." Heymann attributed this debauched tidbit to a "McLean, Virginia, police report…filed on May 25, 1965, signed by Patrol Officer Charles Duffy," who chased after but did not catch the freshman United States Senator from New York as he ran off buck-naked.

There are a few problems with that fantastic tale. Among them: There is no McLean Police Department. The Fairfax County Police, which patrols the area Heymann described, stated in an email that it has no record of an officer named Charles Duffy ever serving on its force. The department also asked 10 officers from that era if they remembered a Charles Duffy. None did. The department also checked its numbered police reports from 1965 and found no such report by any officer.

Then there's the knife that morphed into Champagne in Joe and Marilyn.

In both A Woman Named Jackie and RFK, Heymann recounts Marilyn Monroe's last afternoon alive, August 3, 1962. (Keep in mind that Heymann maintains that both JFK and Bobby Kennedy had affairs with Monroe.) In both of those books, Heymann wrote that just a few hours before Monroe killed herself, Bobby Kennedy and the actor Peter Lawford visited her home in L.A.'s tony Brentwood neighborhood. Heymann said that at one point Monroe pulled a knife and lunged at Kennedy, and that the two men wrested the weapon from her.

When he later told that tale in Joe & Marilyn, Heymann wrote that Monroe tossed a glass of champagne in Kennedy's face.

In the back of that book, Heymann explained how the knife had turned into bubbly. "In an interview with the author, Peter Lawford originally claimed that Marilyn threatened RFK with a kitchen knife; he then revised the anecdote to indicate instead that she threw a glass of champagne at him."

Unexplained is when Lawford changed this story. Lawford died on Christmas Eve 1984, long before any of the three books were published. Putting the best possible spin on things, that means Lawford revised his story before the first book was published. And if that's the case, why did Heymann tell the knife story in the first two books?

The answer, according to Lawford's widow, Patricia, is that Heymann made it all up. She told Newsweek Heymann could not have interviewed her husband on any of the occasions he cited because he was under her care around the clock. Asked if Heymann could have somehow gotten past her, she said Lawford was close to death and hardly able to make coherent statements, much less conduct a lengthy interview.

The Heymann archive at Stony Brook includes his handwritten notes of the purported interview with Lawford. The dying man's supposed words flow smoothly, the way a writer's do after polishing. Most people in interviews meander off-topic, digress and revise their stories as they draw on their memories, especially those who are sick and dying.

A handwriting expert said Heymann's handwritten notes of the purported Lawford interview bore a striking resemblance to the writing in Heymann's purported Hutton notebooks.

Quoting the Dead

In Joe and Marilyn, Heymann drew heavily on the rich trove of books about the Yankee Clipper and the iconic blonde. He also cited interviews with writer George Plimpton; Salinger, the Kennedy White House press secretary; and Newfield. All three men were dead by 2005. Plimpton, in a tape recording in Heymann's own archive, declined to be interviewed. Salinger, in a letter also in the Heymann archive, said Heymann wrote "dramatic lies" and refused to cooperate. We already know that Newfield wrote a column in the Post denouncing Heymann. Despite this, Heymann "quoted" all three men in his book… long after they had been buried.

Among the many statements presented as fact in Joe and Marilyn that might have raised eyebrows at CBS was the one on Page 315. Heymann quoted the late actor and masseur Ralph Roberts as saying that Marilyn Monroe called the White House and "actually told the First Lady she wanted to marry the president," and that Jackie Kennedy, humoring the actress, said "she had no objection."

Yet years earlier, in 1989's A Woman Named Jackie, Heymann attributed that story to Lawford. Only in that version "Jackie wasn't shaken by the call. Not outwardly. She agreed to step aside. She would divorce Jack and Marilyn could marry him, but she [Monroe] would have to move into the White House."

When Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis died in 1994, Heymann rushed out a revised and expanded version of A Woman Named Jackie that fueled a hefty spike in sales, in part because he added a torrid secret affair between the former first lady and her late husband's brother, Robert F. Kennedy, who was assassinated in 1968.

In Bobby and Jackie: A Love Story, he expanded on this theme. He wrote of their supposed tryst on October 18, 1964, at the Manhattan apartment of one of Robert F. Kennedy's sisters, adding that the president's widow and his still grieving brother also shared a "suite occupied by Peter Lawford" at the Sherry-Netherland Hotel in Manhattan. "Although several of the Secret Service files referred to in this chapter are currently available through the National Archives," Heymann cautioned readers, "the majority are not. They were shown to the author by a confidential source."

Donna Morel, a San Diego lawyer whose skepticism about passages in Heymann's books prompted this Newsweek investigation, filed an expansive and carefully crafted Freedom of Information Act request for those files Heymann said were at the National Archives. Morel was notified that "there are no records pertaining to your request." It is possible the National Archives was concealing records. It is also possible that no such archives exist.

Bestler, Heymann's longtime editor, insists that independent fact-checking established the reliability of Joe & Marilyn, but most of Chapter 3 is fabricated. It consists primarily of long quotes attributed to "Rose Fromm, a German Jewish refugee" who Heymann said treated Marilyn Monroe as a therapist. Heymann writes that Fromm told him:

I have to stress that I work as a psychotherapist in Europe but not in the United States and I made that perfectly clear to Marilyn. My doctorate in clinical psychology had been awarded abroad and I had no interest in going through the process all over again.

Heymann wrote that Fromm moved to Los Angeles for six months in 1952, when she treated Monroe, whom she met through two Hollywood journalists she describes as friends, James Bacon of The Associated Press and Sidney Skolsky, then a syndicated Hollywood columnist.

Fromm was born in Sztetl, Poland, not Germany. She arrived in America at age 17, according to her 2007 autobiography. She graduated from the Dante School in Chicago in 1931 and the University of Illinois medical school in 1938, facts supported by photographs and her medical licensing records. Nowhere in her autobiography did Dr. Fromm mention Marilyn Monroe, James Bacon or Sidney Skolsky.

In Joe and Marilyn, Heymann cites Joe DiMaggio Jr., the slugger's only son, as a source on more than 50 of the book's 393 pages. Joe Jr. died in 1999, long before Heymann started work on the book, and he routinely turned reporters away. Public records contradict many of the quotes attributed to him in the book – Heymann wrote that he left Yale for San Francisco, almost immediately married a woman he barely knew, quickly divorced her and joined the Marines. In fact, records and interviews with his friends show, he moved to Los Angeles, joined the Marines before Monroe died (he was photographed in uniform at her funeral) and nine months after her death married a 17-year-old San Diego woman in Southern California. George Milman, a Beverly Hills lawyer who was Joe Jr.'s roommate back then, and Tom Law, a contractor who worked with him, said Joe Jr. was circumspect about his father and devoted to his stepmother.

Heymann also wrote that Joe Jr.'s mother, Dorothy Arnold, took her son and Milman on overnight trips to Mexico where, panty-less, she would do handstands in an apparent effort to channel Monroe's sexual allure. Milman, chuckling, said he recalls a few trips to Baja, but not the rest of that tale.

Earlier, in RFK, Heymann quoted Marie Ridder, a well-known Washington journalist, speculating that Bobby Kennedy "had an affair" with actress Candice Bergen. She says that's not true. Heymann quoted a woman as saying "RFK and Candice made little effort to hide what they were doing." But in a taped interview in the Heymann archive, that source says she saw nothing, knew nothing and asked not to be identified.

When I asked Bergen about this, she exploded with outrage, and then calmly said that none of it was true. She asked of one passage from Heymann's book, more puzzled than angry, "How can he write that?"

The Errors of His Ways

Long after his Hutton book was shredded by Random House, Heymann defiantly defended his work in an interview with The Washington Post. "There's a great degree of difference in the amount of accuracy required between a book about Ezra Pound and a book about Barbara Hutton," he said. "She's not a historical personage—she was a social figure. What I wanted to do was a mise en scène of a life."

He added, "I may have made an error or two, or three, or four, or five—but at least I tried to write an accurate biography."

On its website, CBS urges teachers to assign to schoolchildren Heymann's book about the alleged affair between Bobby Kennedy and Jackie Kennedy. CBS says the book is based on "impressive sources and impeccable insight" so that readers "finally get behind-closed-doors access to the emotional connection between these two legendary figures. An open secret for decades among Kennedy insiders, their affair emerges from the shadows in an illuminating book that only" Heymann could have produced.

The last clause of that statement is true, but in a way they surely don't intend.

Given the abundant evidence that C. David Heymann was extraordinarily reckless with the truth, why does CBS continue to sell his books, and push them on teachers? Most publishers rely on their authors to be truthful, and diligent in their research, and most nonfiction books are not fact-checked by publishers. But when a red flag is raised, publishers have an obligation to their readers to investigate. And when a sea of red flags floods their lobby, they need to start pulping the fiction.