If you have traveled in certain areas of Africa or Asia, you may have noticed children in the street during hours that schools are normally open. You ask them whether they go to school and you may get a hesitant nod, but if you ask them to read something, they cannot.

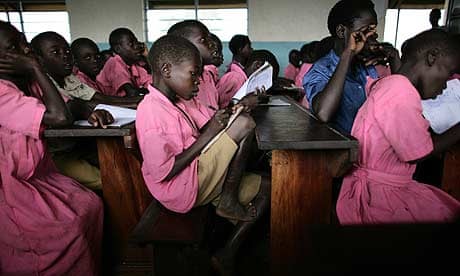

In some countries of great poverty, a new era has started – the era of schooled illiterates. Paradoxically it is a result of strenuous donor efforts to ensure Education for All. Since 1990, herculean feats of fundraising and coordination have been accomplished. Grants have helped low-income countries helped build schools, recruit and train teachers, develop and distribute curricula and textbooks. Much effort has gone into convincing parents to send poor children to school, particularly girls. Consequently, enrollments in sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere have skyrocketed.

But when children start school, something goes awry. Studies show that 80-90% of low-income second graders cannot read a single word. In sub-Saharan Africa, two-thirds of grade 1 entrants drop out by grade 6, and about 25% of the survivors graduate functionally illiterate.

In prosperous countries, nearly everyone learns reading in grade 1, so the poor were expected to perform similarly. The donors recommend greater teacher accountability, more training, stakeholder participation, and preschools run by communities. These might help a bit. But evidence suggests that the real culprit resides in human memory: for reading acquisition and fluency, certain neurological requirements must be met. These include habituation to small two-dimensional symbols and activation of specific areas in the brain.

Better-off children become habituated to letters at home or at preschool, so they quickly learn letters. Children who have never seen a book require guidance to perceive these shapes and understand that they have a "voice". Inexperienced kids may also find it hard to distinguish them at the blackboard. Initially they need big and spaced letters, like those in toddlers' books. Perceptual needs are rarely noted in richer countries, so the research is virtually unknown.

Some may also get marginalised by language and spelling complexity. Nearly all African and Oceanian countries are multilingual, so governments teach in English, French, or Portuguese. These languages, particularly English, have spelling rules that require years of study, even among native readers. Children must learn the languages while learning complex spelling rules, and there are no literate parents at home to help.

With seven hours of school per day and well-trained teachers, most students would manage. But their teachers may know only as much as Australian fourth graders. They are often absent, so the official timetable of four to five periods may get cut down to two. Textbooks are often scarce, and those that exist were made for kids who already own books. They contain many pictures and few words.

According to cognitive science, people learn most efficiently by starting with small chunks – that is, single letters. Practice and feedback compile these into larger chunks, until a certain brain area is activated that recognizes words as if they were faces. Then students start reading effortlessly, and if they know the language they understand. Effortless reading happens around 45-60 words per minute. Many schools catering to the poor do not fulfill these essentially neurological requirements.

Teachers know from experience that few students will perform under these circumstances. Only the brightest students will retain the complex shape of a word or the meaning of a verb heard once and in French. So, many teachers quickly focus their attention on those few (or the financially better off) and neglect the rest. Thus, a class of 60 first graders gets divided in two sections: the best 10-15 students sit toward the front and interact with the teacher. The rest are left on their own.

The ignored students are the up-and-coming illiterates. Their only feedback will be the voices of their classmates. Much of the time they will not be engaged in instruction or know what is going on. They will start skipping class and some day they will not return. By the end of the year, a class of 60 will be reduced to 25 regular students. No alternatives seem evident. "If a child cannot do the work, we send him home" a teacher once said to me in Mali.

Much has been written about the screening-out of the weak, but data are few. Recently, I witnessed the process at a crowded periurban school of West Africa while piloting textbooks in local languages. It was the second week of school, and the teacher of 60 first graders said that "the children" already knew a, i, and o.

To prove it, the teacher wrote tiny calligraphic letters on the blackboard. He asked questions in French, and the hands of about 12 front-row kids shot up. The back rows sat politely, dutifully repeating whatever was said. But they were clearly lost. We showed them a and b in very large print and found that many were unsure about those flat shapes. Some could not see b and b as equivalent; others turned the letter sheets upside down.

Ironically, all that separated the back rows from a brighter future was one or two hours of individual feedback. We tried for 30 minutes with some kids and got them to distinguish shapes reliably.

Even with classes of 60, the process could be formalised. Curricula could prescribe two weeks of perceptual habituation, with the teacher passing by each child to help them understand how letters work. The textbooks for the kids who own no other book should have thousands of words. With individual practice in class and brief daily feedback by the teacher, nearly all should at least read haltingly by the end of grade 1 and attain fluency in grade 2. Simply spelled languages require simple routines, so less educated teachers can master them. In the meantime, the official language must be taught orally, and the spelling rules of English or French can be taught after students read local languages fluently.

This is not just a theory: an experiment in the Gambia in 2011-12 showed that a simple reading program built on memory principles in five languages got good results in the field. If interested countries received targeted attention and advice, students' illiteracy could be eliminated in about seven years.

So why is this memory-based advice not being followed? In the rush to get all children into school, donors and governments skip over low-level learning issues. They are not well known, and highly educated people may find them trivial. Officials are much more interested in higher-level learning, like critical thinking and innovation. International luminaries are also orienting the dialogue towards the high end by proposing large-scale access to the internet in Africa. But there is only way to open the gate to high-level thought: automaticity in reading and also in math. The brain has certain prerequisites, and we have no way of negotiating them. The only thing to do is help governments to fulfill them efficiently.

Educating governments and donors about low-level learning issues is now easier. An international Learning Metrics Task force Initiatives plan to conduct large-scale testing in all countries and follow progress. The results thus far show that students simply score at chance level or below, so solutions are sought. And the effort to teach the marginalised has a new champion: Julia Gillard, former prime minister of Australia. As she wrote in a recent article, testing must lead quickly to instructional improvements.

The 21st century has brought us fairly clear and usable research on teaching the very poor. Truly, more local research is needed, but we know enough to try it out next school year. If first graders learn fluent readers in a phonetically spelled language, they may be engaging in high-level cognition and critical thinking by grade 3. If they do not, they may be the kids you will meet on the street in your next trip to Asia or Africa.