Australians face life imprisonment if they prepare to travel overseas to engage in hostile activities, as part of the most significant overhaul of the nation’s counter-terrorism laws in a decade.

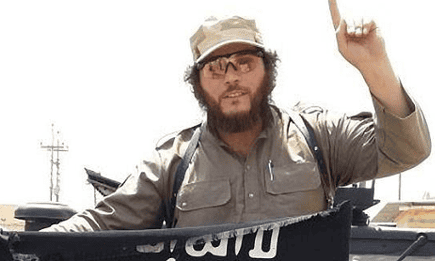

The federal government released its second national security bill on Tuesday evening, arguing the changes were needed to respond to the threat posed by citizens travelling to Iraq and Syria to join Islamic State (Isis) fighters.

The bill seeks to repeal the current regime of laws used to prosecute people in favour of a far more punishing act that creates four offences that carry penalties of life imprisonment.

The four offences where people face life sentences are:

making an incursion into a foreign country with the intent of engaging in hostile activities.

Preparing for incursions into foreign countries for the purpose of engaging in hostile activities.

Giving or receiving goods and services to promote the commission of an offence.

Allowing use of buildings, vessels or aircraft to commit a foreign incursions offence.

The explanatory memorandum of the bill said the severity of the possible sentences reflected “the seriousness of the conduct” involved. The offences require an intention to engage in hostile activities.

In a separate offence that requires a lower threshold of evidence, an entire country can be declared a “no-go zone” that could see entrants to the country jailed for 10 years if they cannot point to a legitimate reason for their trip.

The new offence would criminalise a person entering or remaining in a “declared area” by the foreign affairs minister if they enter or remain in an area that have been proscribed.

The minister can declare any foreign area to be a no-go zone – in a declaration that lasts for three years – if they are satisfied that a listed terrorist organisation is engaging in a hostile activity in the area. The leader of the opposition must be briefed before making the declaration.

The offence will not apply if the person can point to a legitimate reason for their trip. The reasons include providing aid of a humanitarian nature or making “bona fide” visits to family members, appearing before a court or performing a domestic or foreign government duty or a duty for the United Nations.

It also contains a specific exclusion for journalists who are making news reporting of events in the area where the person is working “in a professional capacity” as a journalist.

Contrary to earlier reports, the offence does not shift the onus of proof, and does appear to place a substantial evidentiary burden on the prosecution.

The explanatory notes said the defendant would have to “provide evidence of a sole legitimate reason for entering a declared area which shifts an evidential burden to the defendant”.

“This requires the defendant to adduce evidence that suggests a reasonable possibility that they have a sole legitimate purpose or purposes for entering the declared area,” the notes said.

“Once that evidence has been advanced by the defendant, the burden shifts back to the prosecution to disprove that evidence beyond reasonable doubt.”

The former National Security Legislation Monitor, Bret Walker, told Guardian Australia that while designating a foreign area to be a no go zone was not the only way – or even necessarily the best way – to deter foreign fighters, that the bill did appear to address earlier shortfalls in the existing legislation.

“It seems to me, on my first reading, that the proposals are a serious attempt to permit that balance to be struck trial by trial,” he said.

Substantial concern has been raised around the breadth of the exceptions available, and whether ordinary visitors to countries may be subject to the offence.

Walker said the exceptions appeared to be broadly crafted: “These proposals seem to be to engage the defence only in an evidential burden. That doesn’t require the accused to persuade the court on the balance of probabilities of anything. It only requires them to point to evidence – either you adduce it yourself or to the prosecution – and all it has to be is evidence that suggests a reasonable possibility of something.”

The secretary of the New South Wales Council for Civil Liberties, Lesley Lynch, was critical of the changes to the legislation, saying the government was rushing through the changes.

“The government is rushing through new and as yet unseen ‘foreign fighters’ laws in the super hyped atmosphere post the major counter-terrorism raids in Sydney last Thursday. This is not sound and considered process,” she said.

“The ‘foreign fighters’ bill should be referred to a parliamentary committee and community and independent expert views should be sought.”

The foreign fighters bill is the second tranche of national security changes, with parliament still debating an initial package to increase the powers of intelligence agencies.

The bill also includes the power to suspend a person’s Australian travel documents for 14 days.

A person was “not required to be notified of a passport refusal or cancellation decision by the minister for foreign affairs if it is essential to the security of the nation or would adversely affect an investigation into a terrorism offence”, the explanatory memorandum notes said.

Foreign evidence laws would be amended “to allow the court greater flexibility in determining whether to admit material obtained from overseas in terrorism-related proceedings”.

The bill also includes changes to migration laws to enable automated border processing control systems, such as SmartGate or eGates, to obtain an image of the face and shoulders from all persons who use those systems.

Tony Abbott has repeatedly cited intelligence that about 60 Australians are fighting with terrorist groups in Syria and Iraq, arguing some of them could pose a domestic security threat if they sought to return home.

The prime minister told parliament on Monday Australia might have have to shift “the delicate balance between freedom and security” in the battle against terrorism.

Abbott is travelling to New York for a UN security council meeting chaired by the US president, Barack Obama, to discuss the security threat posed by foreign fighters upon their return to home countries.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion