It was a good week to be talking about data. First there had been that exposé about suspected match fixing in tennis (involving data analysis of more than 20,000 matches); then we learned that the pollsters may have collected data from the wrong people in the run up to last year’s general election.

So when some of the most innovative people working in the field of data and media assembled for the BBC Academy’s latest Data Day conference, expectations were high and the line-up didn’t disappoint.

Happily speakers were less keen on crunching numbers and more interested in revealing the storytelling possibilities that data is already throwing up, as well as some of the head-spinning potential just round the corner.

There was inevitably some challenging ethical debate around privacy and data collection – not just about what that means for Amazon and Netflix but also now the BBC.

In terms of creative opportunities – immediately clear or otherwise – here are just a few of the ideas that caused a buzz among the audience of journalists, programme-makers and technologists in the BBC’s New Broadcasting House:

This BBC R&D prototype allows TV drama narrative to be varied according to audience preference

Visual perceptive media

Say you’re a shy but creative fan of indie music who could be in the mood for some Nordic Noir-style colour grading in your TV drama. Once you’ve punched some profile data into a mobile app (personality traits, music collection, age and gender), a BBC Research and Development (R&D) prototype will customise the look, sound, feel, narrative, character focus and even shot choices of the film to suit or challenge you.

It might even react to your mood in real time by slightly varying or re-ordering the programme’s media components or ‘objects’. Objects are assembled in your web browser using the app data as a guide. Repeat viewing of the customised film could also be altered by your location, time of day – or your mood.

This prototype model (above) obviously requires some extra production effort to supply the variations, but it is just that: slight variations rather than new versions. Ian Forrester, the senior producer running the trial, insists: “It’s a new content experience, not a new service.”

Forrester explains more about this ‘perceptive media’ experiment on the BBC R&D website, where there is also more about what’s meant by ‘object-based broadcasting’.

Will enough people be in the mood to make further development worthwhile? It’s very early days for this particular project and initial feedback from invited participants is still being assessed, Forrester says.

Ad-free and unsensational, De Correspondent mines data for everyday truths.

De Correspondent

In their self-styled mission to “redefine journalism”, the founders of dynamic Dutch start-up De Correspondent and its limited English version have a love-hate relationship with data.

They love what it reveals about the “structures” that don’t usually get the attention of daily news providers: “We didn’t see the 2008 financial crash coming because we didn’t look at the structures behind it,” says editor-in-chief Rob Wijnberg. However they steer away from collecting personal data from the 45,000 paying members who fund their ad-free “online journalism platform” because “we want their expertise, not their demographics,” adds Wijnberg.

The website’s ethos is that what happens every day, the “foundational”, influences lives and world events much more than the “sensational”, what happens as a one-off today. The former is revealed by solid data journalism that interrogates patterns of development; the latter is likely to be an untypical and usually negative occurrence that will grab that day’s headlines. That’s ‘news’ and what they’re aiming for is ‘new’.

De Correspondent has 20 of its own specialist correspondents and around 300 guest contributors, with in-house journalists acting as “conversation leaders”.

Wijnberg says: “We tell them that their real work starts when their story goes online.

“Three thousand doctors who may be among your members know more than one medical journalist,” he reasons.

They vow to stay ad-free, have two million unique users a month and make no claim to objectivity. They’re also link-free. They don’t want readers going off to examine supplementary data on someone else’s website. Instead, they provide layered context in side-notes, within the De Correspondent story.

But can such a model – a “sort of Medium for journalists”, one questioner suggested – survive further expansion without being hijacked by “crazy comments”? Harald Dunnink, creative director, is defiant: “I don’t think size interferes with [our principles]. We can easily ban people, or ask them to be more constructive. It’s our platform.”

Structured stories and the art of repackaging

In case you were wondering “data is just structured stuff”, explains Tristan Ferne, executive producer in BBC R&D. So you can split stories into re-usable components, structure them, label them and put them back together in new ways - a kind of smart digital recycling.

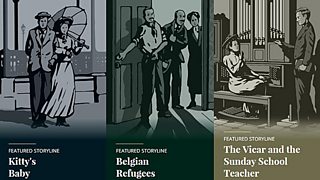

He cites the popular Home Front Story Explorer (above) on experimental platform BBC Taster. Based on BBC Radio 4’s epic daily First World War drama, it allows users to track storylines, follow their favourite characters, replay key moments and remind themselves about timelines and how characters interconnect. In theory the same technique of break down and rebuild could work with any TV or radio drama, as well as factual programmes and news.

The Home Front pilot went down well, with both fans of the series and people discovering it through BBC Taster. Just think what the same treatment could do for War and Peace, Ferne suggests.

‘Atomised news’ is another extension being tested at the BBC: “News events don’t start and stop - some are part of a bigger story and the BBC doesn’t tell stories in one way - so there’s a lot of media to play with,” he says. “Rather than create more stuff, we can re-use well-labelled components.”

Reconfiguring the ‘atoms’ of a news story could let mobile users skim events or dive deeper into much more detail – even tailor results to personal preferences, context and devices. As BBC R&D development producer Barbara Zambrini explains, if your mobile loses bandwidth, a video explaining the story could be substituted with a captioned picture or an audio version if you’ve got your headphones plugged in.

Expect trials of that soon, which might help Ferne and his colleagues answer conundrums like which stories work best and perhaps the million dollar question: “Can we ever tell stories this way as well as hand-crafting them?”

This blog will be following some of the other intriguing developments glimpsed at Data Day in future posts but, if proof were needed that data can be revelatory, open data expert and Imactivate founder Tom Forth had a persuasive example: “We all know that Heathrow is the UK’s hub airport. Right? Well no, it’s Schiphol airport, Amsterdam, according to some fairly simple data bashing by Forth. Undoubtedly the ‘stuff’ of headlines.

Our section on investigative journalism

Our section of digital journalism

Our data journalism blogs by Jonathan Stoneman

#BBCDataDay: Scoops, skills and surprises of data journalism