To Make Roads Safe, Make Them Feel Dangerous

A new study adds weight to the idea that heightening drivers' sense of risk may actually cut down on traffic collisions.

In 2005, the U.K. Department of Transportation unveiled a set of guidelines for what it called “psychological traffic calming,” a strategy to make the country’s roadways safer by giving them a surface-level makeover.

And, also, a tricky little study in semantics: The plan could make traffic calmer, the agency reported, by making the drivers themselves decidedly less so. Suggestions including painting patches of the road different colors, eliminating the lines dividing lanes, and other maneuvers to make the streets seem narrower, windier, and otherwise more dangerous, the Guardian reported at the time.

Around the world, governments have begun to adopt similar measures that promote safety by way of overcompensation, designing environments that force motorists into high alert. A 2003 report from the U.S. Transportation Research Board recommended dividing two-lane highways into a narrower three lanes; towns in the U.K., the Netherlands, and Germany have done away with traffic lights entirely as part of a road-safety initiative called Shared Space, the brainchild of Dutch traffic engineer Hans Monderman.

Earlier this week, a new paper seemed to validate the idea that the best driver is an unsettled one. In a small study published in the Journal of Consumer Research, researchers from the University of Michigan and Brigham Young University found that signs that conveyed a greater degree of motion—think a running stick-figure pedestrian, not a strolling one—may raise drivers’ perception of risk, which may in turn translate to more caution and attention from behind the wheel.

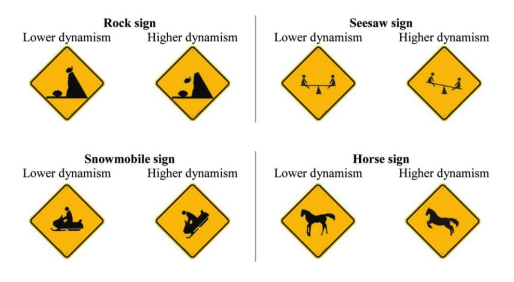

In the first experiment, volunteers were shown four images taken from the driver’s seat of a car, each with a sign (either a high-motion or low-motion version) warning of a different obstacle ahead. The more dynamic warning of falling rocks, for example, showed a boulder in midair, while its less dynamic counterpart had the boulder at the top of a cliff; the more dynamic sign for a horse crossing depicted the animal in mid-gallop, the less dynamic at a more leisurely trot. Using eye-tracking sensors, the researcher were able to evaluate a) how long it took the participants to first notice the sign, and b) how many times they glanced at the area around the sign, indicating that they were sweeping their gaze across the environment in front of them. Across the four signs, they found, the images depicting more movement were both more attention-grabbing—meaning they were noticed more quickly—and more likely to make the volunteers highly attuned to their surroundings, a state the study authors referred to as “attentional vigilance.”

In the second experiment, the researchers created a 16-second driving simulation to test reaction time, asking participants to press a certain key whenever they noticed a warning sign. In the third, designed to test caution, the volunteers were asked to imagine themselves driving and then click to indicate where on a map they would begin to slow down after spotting the sign. And in the fourth, participants were shown two versions of a “wet floor” sign—the kind left in slippery grocery-store aisles—and asked to rate how carefully they would proceed. Across the board, the same pattern from the first experiment held true: The people who saw more dynamic signs were more alert, stopped sooner, and indicated that they would move more slowly than the people who viewed the signs depicting a lower degree of motion.

“From evolutionary psychology we know that humans have developed systems to maximize the chances of detecting potential predators and other dangers. Thus, our attention system has evolved to detect actual movement automatically and quickly,” study co-author Luca Cian, a post-doctoral researcher in marketing at the University of Michigan, explained in an email. “Perception of movement within a traffic sign prepares the driver for actual movement.”

“We would advocate that more dynamic traffic signs be used in contexts where faster attention and reaction times are needed,” added co-author Aradhna Krishna, a professor of marketing at the University of Michigan.

There are others, though, who argue that focusing on the signs themselves—whatever they may depict—are the wrong way to cut down on traffic accidents, which kill around 34,000 people in the U.S. each year, because people may feel like they can rely on the signs and, as a result, don’t need to be as aware of their surroundings.

“A wide road with a lot of signs is telling a story,” Monderman, the Dutch traffic engineer, told Wired in 2004. “It's saying, go ahead, don't worry, go as fast as you want, there's no need to pay attention to your surroundings. And that's a very dangerous message.”