Afiction editor doesn’t control a manuscript’s content, but tries to ensure that the author’s intentions are fully realised. Authors are free to ignore their editors’ advice. I often avail myself of this veto power – sometimes out of a pigheadedness for which I’ll pay the price. But after multiple instances of positive reviews quoting passages that my editor wanted to cut, I figure I’m batting no worse than one for one.

It’s not clear that authors are equally free to ignore the censoriousness of “sensitivity readers”, to whom some American editors are currently sending unpublished work for review. These readers check for any misrepresentations, stereotypes, inauthentic dialogue or anything else that might conceivably offend “marginalised groups”, which include a host of racial, gender, and disability variants. Some books are checked for a potential to cause affront before they are even acquired. Though this practice is now largely confined to children’s and young adult fiction, lately mainstream media have consistently drifted toward pandering to the thin-skinned. Grownup fiction may not stay safe from the sensitivity police for long.

I’m guessing I shouldn’t apply for a job on the force. A recent Hadley Freeman column characterised me as not “known for” my sensitivity. Though uncertain what ghastly brutality has been ascribed to me, I’ve decided to take the thumbnail as a compliment. In this era, it translates: not “known for” equivocation, bet-hedging, and on-the-one-hand mealy‑mouthery. Writers who take on polarising issues are apt to step on a few toes.

Never fear, we’re not rehashing “cultural appropriation”, about which a speech I gave in Brisbane kicked off a debate that grew no little tiresome last year. Yet the advent of the sensitivity reader has a similar gagging effect.

At the keyboard, unrelenting anguish about hurting other people’s feelings inhibits spontaneity and constipates creativity. The ghost of a stern reader gooning over one’s shoulder on the lookout for slights fosters authorial cowardice. Some writers terrified of giving offence will opt to concoct sanitised characters from “marginalised groups” who are universally above reproach. Others will retreat altogether from including characters with backgrounds different from their own, just to avoid the humiliation of having their hands slapped if they get anything “wrong.”

The list of “marginalised groups” whose feelings must be specially protected does nothing but grow. It was news to me that the terminally ill now need to be sheltered from fictional representations of their plight that seem insulting or run counter to their personal experience. Why only the dying? Let’s add eczema sufferers, too.

We might also question what qualifies these self-nominated authorities on sensitivity for their job. As a woman, I’d be uneasy about being given the power to determine what is insulting to women in general. Membership of a group doesn’t make one an expert on that group, and doesn’t preclude misconceptions about one’s own kind. A British book reviewer once ridiculed this American author for not knowing the difference between “wanker” and “tosser” – when both words allude to male masturbation, and they differ only in colour (right, “tosser” can be backhandedly affectionate, a subtlety that the text reflected). Yet because the reviewer was British, she didn’t question her expertise on British slang.

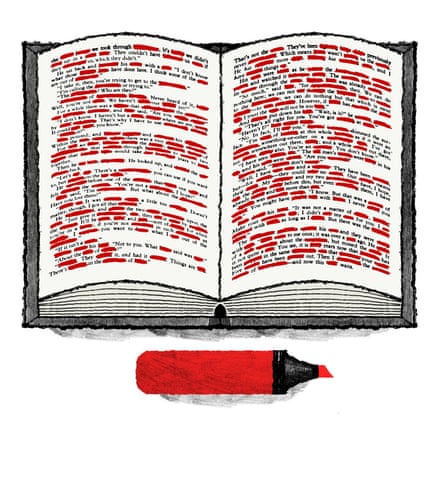

Employees instinctively justify their existence as well. Thus the sensitivity police are seldom going to wave any book through without highlighting a goodly handful of grave sins that validate the $250 reading fee. (I have to say, these people are underpaid. Being professionally offended all the time must be exhausting.) We are literally turning umbrage into an industry. When you reward touchiness, you only get more of it. Thus even after these manuscripts are purified, someone out there is bound to find more transgressions in the published version.

There’s a thin line between combing through manuscripts for anything potentially objectionable to particular subgroups and overt political censorship. Is it any longer acceptable for characters to be bigoted? Can a character in your novel vote for Brexit? And if all the characters speak with the same courtesy, and voice the same standard left-of-centre views, contemporary fiction can’t hope to contribute to the understanding of a world that elects Donald Trump. Fiction won’t help younger readers to make sense of their real lives, if in books Muslim men never groom white girls or become radicalised through the internet, transsexuals never regret transitioning or conclude they’re actually gay, women are always confident and empowered, and the terminally ill are always brave (or whatever they’re supposed to be; ask the experts). These days, with all hell breaking loose in Europe and the US, the left’s sensitivity run amok seems to be coexisting in a bubbled‑off alternative universe.

Surely the texts of numerous books, films, and TV shows already in the cultural canon would never make it past sensitivity readers. Subject to extreme vetting, David Simon’s The Wire would never have been made, Richard Price’s Clockers never written. African Americans as addicts and drug dealers? Stereotypes! Forget Netflix’s Narcos, which shamelessly portrays Latinos as murderous druglords. Not only all those bearded villains in Homeland, but Yasmina Khadra’s nuanced trilogy about Islamic fundamentalism would never get past scolds determined to discourage the branding of Muslims as terrorists.

The texture of this procedural innovation is Soviet. If books don’t adhere to the party line, they’ll not see print, and the authors will be re-educated. That’s what’s already happening in YA fiction. The publication of Keira Drake’s 2017 fantasy novel The Continent has been put on hold because of ostensible racial stereotyping. Her publisher has posted: “We have listened to the criticism and feedback and are working with the author to address the issues that have been raised.” Poor Keira is probably sweating it out in some Manhattan gulag.

While I don’t choose to be gratuitously offensive in my novels, I can’t keep others from becoming incensed anyway, now that indignation has become an international sport. Like other responsible colleagues, I do my homework. But good fiction is daring – it takes risks – and too much contemporary fiction is already bland. The publishing industry doesn’t need more gatekeepers to make it blander yet and still more timid. The day my novels are sent to a sensitivity reader is the day I quit.

Lionel Shriver’s most recent novel is The Mandibles: A Family, 2029-2047