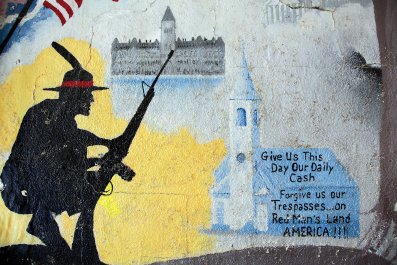

It seemed like old times: In Havana in early July, Castro, the revolutionary leader of Cuba, embraced the current occupant of the Kremlin—once upon a time the isolated Communist island's sugar daddy—together gleefully sticking a finger in the eye of their Cold War rival in Washington.

In this case, the Castro was Raúl—the younger brother of the ailing (or still alive?) Fidel—who now runs Cuba, and Vladimir Putin, the Russian president, who seems driven to not only reconstitute (to the extent he can) the Soviet Union but also to put the old band of anti-American developing-world countries back together again. This was the second visit from Russia's leader since the Soviet Union fell apart and—much to Havana's fury—Moscow effectively dumped it as an unaffordable client state.

But as Putin, since his annexation of Crimea in March and his backing of Ukrainian separatists, has become increasingly hostile toward the West, his Cuba visit raised an important question: In 2014, is a Moscow-Havana alliance as potentially consequential for the United States and its allies in the region as it once was? These, after all, were the players that in 1962 brought the world to as close to nuclear Armageddon as it has ever been.

Putin's motives for establishing closer ties with not only Havana but other like-minded countries in Latin America—Venezuela and Nicaragua specifically—seem straightforward. In the wake of his push into Ukraine, Russia's relations with the West are deteriorating rapidly. So in the East he signed a massive gas deal with China (the two powers have long viewed each other warily at best), then looked south for a back-to-the-future moment with Cuba.

During the visit, Putin agreed to write off $32 billion in Russian debt to Cuba, leaving just over $3 billion left to pay over the next 10 years. This was a significant economic weight lifted from Havana, whose gross domestic product shrank by up to a third with the loss of direct aid and subsidies from Moscow after the Soviet Union fell. Putin and Raúl Castro also agreed to new deals in energy, health and disaster prevention and help with building a vast new seaport. Moscow is also now exploring for oil and gas in Cuban waters, right in the U.S.'s backyard.

The deals were the most pronounced sign yet that the formerly estranged couple were reconciling—a process that has been under way for more than a year. Early in 2013, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev visited and agreed to lease eight jets to Cuba. In June, as part of a "space cooperation" agreement, Cuba said it will allow Moscow to base navigation stations for its own global positioning system, called Glonass, on the island.

"What Putin is doing is reestablishing the relationships that, when Russia was turning west, planning to become part of wider Europe, and giving up the legacy of the Soviet Union, were actually neglected," says Nina Khrushcheva, an associate professor of international affairs at the New School and granddaughter of former Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev. "I think that stands at the core of his reengagement."

But Putin didn't show up in Havana simply to sign trade deals. The former KGB man had more on his mind than a photo op before flying back to Moscow. Important strategic moves were made. In exchange for canceling the Cuban debt, Russian news outlet Kommersant reported, Russia plans to reopen the so-called Lourdes spying post. Opened south of Havana in 1967, Lourdes was the largest and most extensive Soviet signals intelligence facility outside of the Soviet Union for much of the Cold War, says Austin Long, an assistant professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University.

Moscow closed Lourdes, which operated only 150 miles from the Florida coast, in 2001. At its operating peak, more than 75 percent of Russia's strategic intelligence on the U.S. came through Lourdes, including monitoring NASA's space program at Cape Canaveral.

While there are doubts over just how quickly Russia can reopen the 28-square-mile compound—and, considering Putin has actually denied the reports, whether it will even open—the news is still significant. "It indicates a real effort by Putin to revitalize the worldwide rather than just regional capabilities of Russia for intelligence collection, and maybe eventually for the protection of military power," says Long.

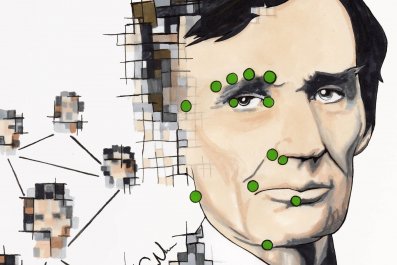

Deeper than that is Russia's realization that it may be lagging far behind in the murky realm of cybersecurity, particularly after Edward Snowden's National Security Agency leaks, Long said. But there is another way of looking at Russia's spying ambitions in the wake of the Cold War. If, as has been widely speculated, Snowden, whom Putin has just awarded a three-year visa to remain in Russia, was a Moscow spy from the start, far from lagging in the cyber-spying race, Moscow may be a nose ahead of the U.S.

"I think this is partly an attempt by them to reopen a facility that gives them some access, at least in theory, into the West," Long said. "The Russians are okay on low-level cyber stuff, but I don't think they've kept up overall in terms of signals intelligence, certainly not over what the U.S. and the U.K. have done over the past decade."

And while information-gathering technology may have changed beyond all recognition since the late 1960s—with satellite technology rendering ground-based operations largely useless—if Lourdes does reopen, Russia can provide information to allies like Venezuela and Bolivia, says Robert Jervis, a professor of international politics at Columbia University.

"I think there's real benefit [to reopening Lourdes]. After all, the U.S. tries to vacuum up everything imaginable, so we shouldn't be surprised that Russia would want to do likewise," he said.

Moscow's moves puts Cuba in play as an asset to annoy the U.S. at a time when relations are worse with Washington than at any time since the end of the Cold War. And they come amid evidence that Washington under the Obama administration hasn't exactly been ignoring Cuba from an intelligence standpoint either. The Associated Press recently revealed that in 2009 the U.S. ran an operation, under the guise of the U.S. Agency for International Development, sending young Latin Americans into Cuba in "hopes of ginning up rebellion."

The Russian rapprochement goes way beyond the potential reopening of Lourdes. Last year, Russian Chief of Staff General Valery Gerasimov visited key intelligence sites in Cuba. One year after Medvedev's visit to Cuba in 2008, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced that Russia had engaged in talks to establish military bases in Cuba as well as Venezuela and Nicaragua.

"Anything that annoys the U.S. probably makes Putin feel better," Jervis said. "It's symbolic muscle-flexing."

How seriously should Washington take Russia's reengagement with Cuba? Regional experts both in and out of government say, for the moment anyway, not very. The reopening of Lourdes isn't going to threaten U.S. national security when organized crime, drug trafficking and uncontrolled migration are top priorities for the U.S. in Latin America, says Joaquín Roy, a professor of European integration at the University of Miami.

"Russia doesn't have the military or naval capability of converting this into a beachhead of operations in Latin America," Roy said. "If someone believes that, this is totally silly."

Still, Putin is a shrewd image-builder and will seek out and exploit those countries disappointed in the United States, Khrushcheva says. "It's the image-building for those who have been incredibly disappointed by 20-plus years of U.S. lone leadership of the world," she said.

And in the spying game—as in real estate—location counts is paramount. Ultimately, Cuba's proximity to the U.S. gives it value to a Russian president who has decided he wants to make life as difficult for the United States as he is able. And Obama's comments in March this year, after Putin's Crimea invasion, that the U.S. is working to "isolate" Russia from the international community, only gives Moscow more incentive to re-engage Havana.

Putin's Cuba trip, says Stephen Cohen, professor emeritus of Russian studies at Princeton University, "was a reply to Obama's notion that Russia could be isolated, by saying, 'Hey, here we are back 90 miles off your shore with a big greeting, and we're going back into economic business here.'"

While the revival of the lapsed Russia-Cuba love affair might be an irritant to a United States that has long hoped the demise of Fidel Castro would finally bring an end of Cuba's isolation—and possibly a reorientation toward Washington— the U.S. has much bigger problems with Moscow these days. And Russia simply doesn't have the wherewithal—despite its oil and gas wealth—to refight a cold war in all the old venues.

"If you compare [the Russian threat today] to the Soviet Union 30 years ago, that was a large scale, global challenge," says Columbia's Austin Long. "I think Putin certainly has ambitions to restore global stature to Russian power, but we're just not there, and I don't see any prospect that we will be."

Putin may punch above his weight, but at some point, reality sets in. "The gap in capabilities between the U.S. and Russia now," says Long, "and the Soviet Union and the United States 30 or 40 years ago is just much, much greater."