One of the most important experiments of modern times began in Bradford on 17 April 1907 – and it centred on porridge. Officials went into one of the poorest parts of the city, picked about 40 of the most deprived schoolchildren and began feeding them breakfast and dinner for free. The group got oatmeal porridge every morning, made with milk and treacle, followed by bread and dripping and more milk to drink. The Boer war had turned the malnutrition of working-class British soldiers into a scandal, prompting the government to allow local authorities to give free meals to poor children. And one of the world’s great industrial metropolises was also becoming a birthplace of the free school dinner.

Over its three months, the experiment worked – up to a point. In their report on “a Course of Meals given to Necessitous Children from April to July 1907”, officials include a handwritten graph charting how the 40 human guinea pigs began putting on weight week after week. As the ounces pile on, the line shoots up and up – until, all of a sudden, the graph hits a shaded section, and a steep downslope as the children get thinner. Just why is explained by the capitals written across this period: SUMMER HOLIDAYS. School is out, free meals are over – and the group starves.

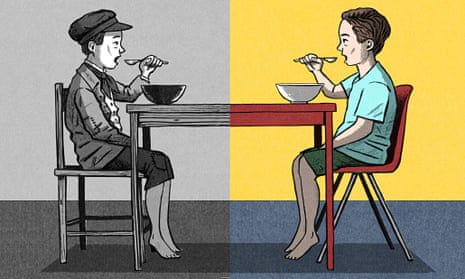

In the century since, Britain has grown rich beyond compare. Indeed, it is wealthier and healthier than at any point in history. Britons are better fed than ever, too: dripping no longer counts as a treat; Peruvian ceviche does. Yet amid this exotic plenty, the curse that beset those Bradford pupils continues to visit classrooms across Britain: holidays still inflict hunger on poor children and their families.

This is Britain in 2015: glutted with iPads, permanently distracted by Facebook – but riddled with Victorian-style poverty. Just read this observation from the Magic Breakfast charity, dating from August 2014, yet documenting the same phenomenon seen in Bradford in 1907: “Teachers tell us they know even with free school meals it will take two to three weeks to get their kids back up to the weight they were at the end of the last school term because their families cannot afford the food during the holidays.” Listen to the reports from GPs in gentrifying parts of Britain, such as the East End, who see patients suffering rickets: “It is a condition we believe should have died out.” Scan this month’s survey from Kellogg’s, in which six out of 10 parents on household incomes of £25,000 or less admit they cannot always afford food outside term time.

This is what a society looks like when it hurtles its richest members into the future, even while kicking its poorest back into the grimy past. And to see it up close, do what I did last Friday: visit Dorchester’s Thomas Hardye school out of term. Turn up at the dining hall around lunchtime, and you’ll find a handful of volunteers serving a free lunch to local children and their parents. During term, the children would be entitled to free school meals; over the holidays, that particular safety net disappears.

This is where family poverty hides out in the holidays: a brightly coloured dining room with classroom art plastered across the walls and chunky plastic cutlery in serving baskets. The holiday kitchen has been running for four years and even in picturesque Dorchester is getting busier and busier: it’s on course to serve more than 500 meals in the next few weeks. The volunteers here are affiliated to the Make Lunch charity, whose slogan is “Free school meals when there’s no school”. The network is already heading for about 40 kitchens this year: from Aberdeen to Salford to Thurrock, Essex.

In Dorchester, I joined Andy and his 13-year-old Matty (not his real name) for fish and chips. Andy was a soldier in the Falklands turned chef, owned a restaurant, even cooked for royalty – then came a string of health problems, beginning with a collapsed stomach and ending up permanently disabled, on crutches and unable ever to work again. As a journalist writing on these issues, I have got used to this routine: interviewees claiming social security so desperate to show that they are not typical Benefits Street residents that they will spill mortifying personal details to a stranger with a notepad.

Andy wanted me to know he agreed with David Cameron’s cuts – but what also sang out from his story was how badly he’d been let down by the state: the family had had to wait months for their benefits to start, the bedroom tax meant that they were paying extra rent for a room to house his hospital-issue bed and equipment.

This was Andy’s first week visiting the kitchen: in previous holidays “we’d skip not just meals, but whole days”, so the two children could be fed. Then there were the holiday clubs still to be paid for. Matty and his sister got secondhand birthday presents; their parents let birthdays, wedding anniversaries and Christmas slide by without so much as a card.

Allow me to be upfront about my ambivalence. Volunteers at Make Lunch (and other similar ventures) do a brilliant job. They source and cook food and find kitchens and dining halls. For Iain Duncan Smith and his colleagues, this is success. “I welcome food banks,” the welfare secretary said last month. “I welcome decent people in society trying to help others who … have fallen into difficulty.” So Andy and his family are now at the front line of a new society, where the state is beating a rapid withdrawal, while charities and schools try to fill in. Inevitably, they do so patchily and partially: battered parts of Weymouth need a holiday kitchen far more urgently than Dorchester, but it doesn’t yet have the volunteers.

Then you hear stories like how Andy’s wife turned up on the first day before the doors opened, and got so embarrassed she tried to steal away. “It’s upsetting,” she says, turning away and dabbing at her eyes. A wealthy country unwilling to feed all of its citizens ought to feel a collective shame; but in Britain it is the poorest individuals who suffer the most corrosive guilt.

What kind of society is Britain creating for its poor? For me, it is Victoriana; for Rachel Warwick of Make Lunch, the bottom of British society resembles a kind of Live Aid. But it’s Andy’s view that rings in my ears. After saying his goodbyes, he turns back: “Places like this are going to be the future.”