Estancia Arco, Bolivia: 2005

There are 25 Quechua families in the community of Estancia Arco on Bolivia’s altiplano – that’s approximately 400 people. In 2004 six mothers and children died here during childbirth. The nearest medical help is a hospital three hours away by bicycle. Then it takes another hour for the ambulance to reach the community and a further hour to take the patient back to the hospital. That means any mother or child requiring urgent medical attention will have to wait a minimum of five hours before receiving treatment.

The hamlet lies 4,000 metres above sea level, set in a small plain near a dry riverbed. The fertile soil is being polluted by the dumping of mine waste and by the natural salts and mineral residues left after the rainy season, which gets weaker and weaker every year.

“Every year I produce less and less potato, barley and wheat,” says Estancia Arco resident Serefina, when asked about her crops. There is never a surplus to sell in the distant markets. Most years there is barely enough to feed the family. Even if there was a surplus the prices are so low that any revenue would be swallowed up by the cost of transport to get to the market. Deforestation and erosion have added to the daily struggle to survive as there is less and less firewood and the land becomes more barren. These residents have come into conflict with neighbouring villagers as they are forced go further afield to collect firewood and find grazing land for their animals.

Estancia Arco: 2010

Five years later, only two village women have died during childbirth in the intervening period, a direct result of monthly visits by a newly established medical auxiliary unit. Child mortality rates have also been slashed because – as elsewhere in the country – women who attend free pre- and post-natal clinics have been rewarded with cash and monthly food parcels. In addition a one-room school has been opened, built by a non-governmental organisation and with teachers provided by the government.

The issue of education is still not a straightforward one for Martha and Anselmo and their children. For generations, the family have scraped an existence by herding llamas and sheep on the altiplano. Their eldest daughter, Eugenia, helps to prepare meals, fetch water, tend the potato field and shepherd the animals. Neither she nor her two sisters go to school, just their elder brother Zenobio, who sets off before sunrise every day to walk the three hours to the nearest school. Village elders are reluctant to allow the girls to be educated for a number of reasons – the dangers of returning after nightfall, the loss of their labour, and the expense of school materials.

In 2010, Anselmo sells half of his llamas to purchase a plot of land in nearby Oruro. He is determined that all his children should go to high school and learn Spanish, to help free them from poverty. In the tiny, breezeblock house, the six brothers and sisters share two beds. Anselmo works in the city from time to time as a porter to supplement their income, leaving Martha back at the village to look after the llamas. Estancia Arco: 2015

One by one, Martha and Anselmo’s children have dropped out of school. The Quechua-speaking children found learning Spanish too great a challenge, their mental development having been crippled by years of poor nutrition. Eugenia and her sister Nieves have begun to sell clothes in the market at Oruro. Zenobio, the eldest boy, has started importing used cars from Chile – he hopes to go to night school and study to be a car mechanic. Elisabeth, the youngest girl, has found a job as a domestic worker. By 2015, only Limbert, 10, and Uber, eight, remain at school, returning home to the altiplano during holidays.

Reyna and Cintia, Tegucigalpa, Honduras: 2005

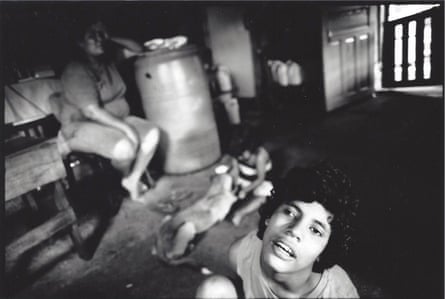

Reyna and her family live in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, a country with the highest murder rate in the world. Her daughter Cintia is disabled. She cannot walk unaided. She cannot talk other than to say Ma or Pa when hungry. She plays with no toys or games. She enjoys rolling on the floor. Because of the need to watch her, Reyna has never been able to leave the house to find work, which would give her the money she needs to send Cintia to a school for children with disabilities. Instead she sells tortillas that she cooks on a wood-burning stove on the porch. Smoke billows into the house and Reyna worries that Cintia might one day burn herself.

It is also very difficult for Reyna to take Cintia to therapy at the Public Rehabilitation Center, since it is hard to move around with her. Cintia has no wheelchair, so Reyna must carry her daughter on her shoulders. This is increasingly difficult, as Cintia is getting bigger and heavier. “But I am so blessed,” Reyna says. “Fifty-nine babies died in the hospital in the month that my Cintia was born. God gave her life.”

Reyna and Cintia, Tegucigalpa: 2010

Five years on and nothing has changed for the better in Reyna and Cintia’s lives. Reyna herself has become incapacitated, trapped in the house and in constant pain from the years of carrying her disabled daughter. The family receive no state help. “The government doesn’t help the poor, only the rich,” says Reyna. “They don’t even listen to the poor. We don’t receive any social assistance. We have to look after ourselves.”

Reyna and Cintia, Tegucigalpa: 2015

Reyna, now 43, and Cintia, 19, still live in the same house, in the same room. Reyna’s husband Benancio now works in construction and – in his spare time – he has added a small balcony to the house. But now Reyna worries that Cintia could fall from it. “The neighbourhood where we live is dangerous,” she says. “We have problems with violence and gangs. I trust in God to protect my family.” Nothing has changed.

Franklin and Maria Enma, Tegucigalpa: 2005

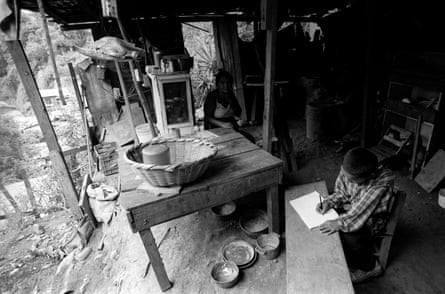

Franklin, five, lives in Isla Perdida in Tegucigalpa. Isla Perdida – or Lost Island – is a hidden ghetto, clinging to the steep banks of the Rio Chiquito. It is a place of mudslides and sudden violence, barefoot children and wild roaming dogs. Yet in its makeshift homes, above a twisting river running dirty brown with effluent, Franklin is growing up as a studious boy. His grandmother, Maria Enma, cannot read or write, but Franklin is in school, “because this will be the only good thing we will leave him, along with this house”, says Maria. Her grandson is happiest when reading, writing and doing his homework.

Franklin and Maria Enma, Tegucigalpa: 2010

Five years later, Franklin is top of his class in primary school. A near-perfect mark in mathematics earns him a place at secondary school. He dreams of becoming a banker. But although education is free in Honduras, neither his grandmother nor his mother can afford the expense of his daily bus fare to the new school, let alone the $25 needed to buy a uniform. Franklin has no choice but to stop his education.

Franklin and Maria Enma, Tegucigalpa: 2015

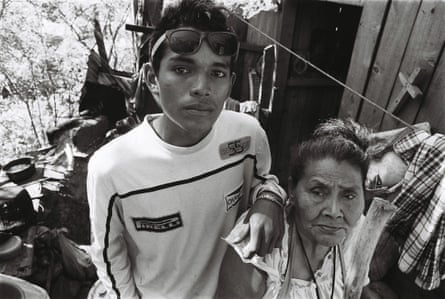

Today Franklin is vulnerable, jobless and racked by disillusionment and crumbling self-esteem. His recruitment by a neighbourhood gang has cast a dark shadow over his life. The promise of good money led him to deal in drugs, until the night he and four friends were caught by the police. Two of the boys were executed on the spot. Franklin’s life was saved only by the intervention of his mother.

Franklin has tried to extricate himself from the gang but its leaders will not let him go. When he refused to deal again, they threatened to kill him. To protect himself Franklin carries a knife. As so often is the case, he has become hooked on drugs and is trapped in addiction and poverty.