A military lesson the United States seems doomed to constantly forget and painfully re-learn: unclear goals invite escalation.

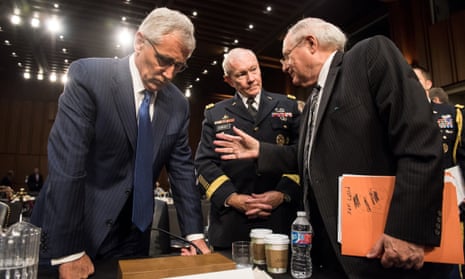

The third Iraq war is now the latest example. At a Senate hearing on Tuesday, the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, General Martin Dempsey, opened the door to US military personnel joining in the ground fight against the Islamic State (Isis). Just don’t call them ground troops. So far, US forces in Iraq have been described as embassy security or “advisers” – Dempsey extended the circumlocution to suggest they might be asked to do some “close combat advising”.

Dempsey’s euphemism bursts the seams of Barack Obama’s insistence that US troops will not return to combat in Iraq. That was itself a rhetorical escalation from the White House’s earlier assurance against troops on the ground, full stop, which has proved difficult to square with the current 1,700 US troops now in Iraq, 1,600 more than were there in June. Perhaps more candidly, Dempsey said Obama has asked the general to come back for “case-by-case” authorization on involving US troops in combat, even as the president again forswore ground combat in a speech at MacDill air force base on Wednesday.

Nor will the ground force plus-up be the US’s only escalation. Air strikes, 167 of them thus far, occur daily; have expanded from Iraq’s north to south-west of Baghdad; and will soon target Isis in Syria. Chuck Hagel, the US defense secretary, acknowledged that the first cohort of US-trained Syrian rebels “is not going to be able to turn the tide” against an Isis force that officials estimate can muster 31,000 fighters. Nor has the US firmed up a Middle East coalition that can sustain that proxy army in the Syrian field.

Steadily increasing men and money ($7.5m every day, per a late-August Pentagon total) into Iraq follows from the goal Obama laid out last week: to degrade and ultimately destroy Isis. It signals toughness and finality, yet its meaning is elusive.

Anything that reduces Isis’s capabilities – say, by blowing up its artillery, trucks and checkpoints – counts as “degrading” the jihadist army. Destruction sounds comparatively unequivocal, until the “ultimately” qualifier punts the destruction to the realm of aspiration. Dempsey testified that destruction will be a “generational” event, occurring when Sunni Arabs reject Isis’s ideology, prompting the question of when the US military will know it can stop bombing, particularly as most Sunni Arabs already reject Isis as barbaric fanatics.

It is a question that the US for decades has proven far better at deferring than at answering, all at the cost of countless lives, dollars and victories.

In Afghanistan, Obama’s goal for his 2010-11 troop surge was to “break the Taliban’s momentum”, whatever that meant. Its result has been to live with a diminished form of the Afghan insurgent force while a diminished US presence stretches the war through 2016 and, pending a garrisoning agreement, to 2024.

Obama’s goal against al-Qaida was to “disrupt, dismantle and defeat” the organization in Afghanistan and Pakistan. At the moment, that looks successful, as al-Qaida’s core has neared irrelevance since Obama ordered Osama bin Laden’s 2011 killing. Except that US drone strikes in Pakistan continue, most recently on Sunday, suggesting a lack of confidence in the durability of US achievements.

Al-Qaida’s franchising has proliferated the US response to Yemen, Somalia and other battlefields shrouded in official secrecy. That secrecy spares official Washington the need to even explain what it seeks to accomplish and renders the perpetuation of missile strikes and raids as their own success.

Obama follows in an ignominious presidential tradition. George W Bush’s goals for the second Iraq war pivoted from the mirage of eliminating weapons of mass destruction to the overthrow of Saddam Hussein to the preservation of something resembling democracy. That war’s most successful period adopted the more realistic (if undeclared) goal of making Iraq somewhat less violent, and even that required a major troop escalation.

The pattern has held, with few exceptions, since the second world war ended. Korea’s “police action” resulted in a gruesome stalemate once Douglas MacArthur reinvented the war from the preservation of a US ally in Seoul to the destruction of Moscow’s ally in Pyongyang. As many as two generations of US policymakers wish to get over Vietnam, their unrealistic guarantees to foreign proxies and preference for military solutions to entrenched, obscure political challenges repeat the central mistakes contributing to a traumatizing escalation.

US wars are more likely to end through an exogenous event – such as Russia’s diplomatic restraint of Serbia to end the 1999 Kosovo air war or Libyan rebels’ killing of Muammar Gaddafi to end the 2011 Libya air war – than through the deliberate application of military force.

The now-classical exception is the first Iraq war. Its goal, the removal of Iraqi forces from Kuwait, was as clear as it was achievable through the introduction of overwhelming military power. It accordingly obviated the need for escalation through its swift victory. Its tragedy was the post-facto establishment of removing Saddam Hussein as a goal of US policy, which has sunk the US ever deeper over 23 years into Iraqi affairs it does not understand and has a poor record of influencing.

Only in the first Iraq war did US policymakers make a frank and up-front commitment about the substantial costs required to achieve their goals, an often-forgotten political risk for the first post-Vietnam ground war. Before and since, the American preference has been to blur those goals, the better to appear forceful. Yet the costs of setting unclear and moving targets are compounded violence and actual victory.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion