How Older Brothers Influence Homosexuality

Homosexuality might be partly driven by a mother’s immune response to her male fetus—which increases with each son she has.

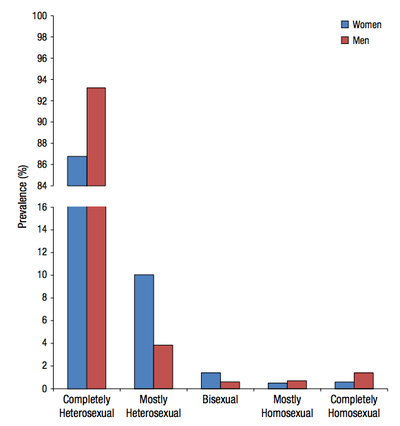

Here’s what we know: Homosexuality is normal. Between 2 and 11 percent of human adults report experiencing some homosexual feelings, though the figure varies widely depending on the survey.

Homosexuality exists across cultures and even throughout the animal kingdom, as the authors of a mammoth new review paper on homosexuality write. Between 6 and 10 percent of rams prefer to mount other rams, not ewes. Certain groups of female Japanese monkeys prefer the company of other females:

In certain populations, female Japanese macaques will sometimes choose other females as sexual partners despite the presence of sexually motivated male mates. Female Japanese macaques will even compete intersexually with males for exclusive access to female sexual partners.

Here’s what we don’t know: What, specifically, causes someone to become gay, straight, or something in between. Part of the explanation is genetic, but because most identical twins of gay people are straight, heredity doesn’t explain everything.

The “why” question is important because “there is a strong correlation between beliefs about the origins of sexual orientation and tolerance of non-heterosexuality,” according to the report authors, who are from seven universities spanning the globe. Specifically, people who believe sexual orientation is biological are more likely to favor equal rights for sexual minorities. (When Atlantic contributor Chandler Burr proposed in his 1996 book, A Separate Creation, that people are born gay, Southern Baptists called to boycott Disney films and parks in protest against the publisher, Disney subsidiary Hyperion.) It shouldn’t matter whether people “choose” to be gay, but politically, it does—at least for now.

One of the most consistent environmental explanations for homosexuality is called the “fraternal birth order effect.” Essentially, the more older brothers a man has, the more likely he is to be gay. The effect doesn’t hold for older or younger sisters, younger brothers, or even for adoptive brothers or stepbrothers.

According to Ray Blanchard, a psychiatry professor at the University of Toronto, the reason could be that the mother’s body mounts an immune attack on the fetus of her unborn son. As the report authors explain:

Male fetuses carry male-specific proteins on their Y chromosome, called H-Y antigens. Blanchard hypothesized that some of these antigens promote the development of heterosexual orientation in males … Because these H-Y antigens are not present in the mother’s body, they trigger the production of maternal antibodies. These antibodies bind to the H-Y antigens and prevent them from functioning.

With the H-Y antigens not functioning, it could be that the “be straight” signal in the fetus’s brain never flicks on.

Blanchard believes that this phenomenon grows stronger with each boy a woman bears. Studies have found that a man without older brothers has about a 2 percent chance of being gay, but one with four older brothers has a 6 percent chance. (Meanwhile, other studies have found the relationship to be weak or nonexistent.) As psychologist Ritch Savin-Williams writes in an accompanying commentary, the outcome for any given baby boy might depend on the timing of the immune response and the fetus’s susceptibility to the antibodies.

According to the report, Blanchard now plans to test mothers of gay and straight men for the presence of these antibodies. If proved out, fetal birth order could do a lot to fill in the missing explanations for homosexuality. But gaps will remain, such as why some firstborn sons are gay, why some identical twins of gay sons are straight, and why women are gay, to name just a few.

The review-paper authors do rule out one explanation for homosexuality, however: That tolerance for gay people encourages more people to become gay.

“Homosexual orientation does not increase in frequency with social tolerance, although its expression (in behavior and in open identification) may do so,” they write.

That reasoning—that a tolerant society somehow encourages homosexuality to flourish—has been used to support anti-gay legislation in Uganda, Russia, and elsewhere. These laws do marginalize and shame gay people, the authors write. But they won’t do away with a sexual orientation that’s ubiquitous, enduring, and—whether through genes, or hormones, or antibodies—perfectly natural.