As a fraught and worn-out Greece careered this week towards a historic vote that could determine its future for generations, one image has captured the country’s dilemma.

Websites, TV stations and newspapers around the world have shown it: daubed on a wall in Athens, the EU flag, its azure background and 12 gold stars – one of them red – defaced with four bold white letters: N€IN.

“It came to me the other day, so I went out straightaway and made it,” said N_Grams, a 34-year graphic designer who prefers to be known by his street artist’s tag, while sitting in a basement studio in the city’s fashionably grungy Psirri quarter.

“Because this is it now, isn’t it? Crunch time. The moment has come. Now we have to make the the big choice, the really big decision. Perhaps this will make some people think.”

Hours from a Sunday referendum that could conceivably end up tipping Greece out of the eurozone and into a deeply uncertain future, Athens’ street artists know where they stand.

“It will be hard to go it alone, but at least we will be free again,” said Cacao Rocks, 30, who in partnership with N_Grams has produced some of the capital’s more striking recent street works.

“We have to stand up for ourselves, for our rights – and it will be the choice of the people. I am a little scared now, though.”

Anti-austerity street art has flowered in Athens and other Greek cities, as the country has endured five brutal years of economic collapse and social hardship that have seen unemployment soar to 26% and the economy shrink by a quarter.

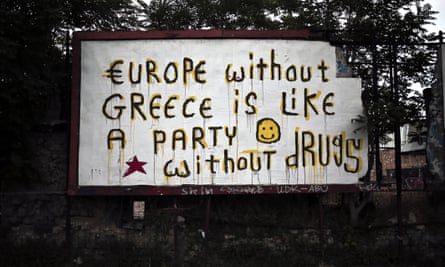

Former photographer Cacao – responsible for works including “€urope without Greece is like a party without drugs”, “Cut the Debt”, “IMF Go Home”, and the now infamous “Then they used tanks. Now they use banks” – said Greece’s long-flourishing street art scene had exploded since the crisis began.

“Partly it was because of this big wave of anger that started in 2008 and just grew and grew,” he said. “But also, as the crisis got worse, there were more and more closed shops and empty buildings. There were a lot of walls to paint.”

The two artists survive by selling the odd resolutely non-political artwork, often to tourists, and frequently have to scrounge or improvise for paint and materials. “We don’t sell our beliefs,” Cacao said. “We don’t want to make money out of saying austerity is unjust and clearly isn’t working.”

Other artists have adopted different media. Since 2014, Stefanos, a 29-year-old graphic artist in Athens who did not want to give his surname, has been turning every euro banknote he can find into an illustrated affirmation of what he sees as the currency’s evils.

From the ornate baroque arch that adorns the front of a €100 banknote, the tiny figure of a man, drawn in black ink, hangs by his neck. Passers-by, one a child, look up at the swinging corpse, aghast.

On a €5 bill, the grim reaper stands beneath a more classical temple, hooded and menacing, scythe in hand. And with boots and hammers, a small crowd are merrily smashing the leaded gothic windows on a €20 note.

Each drawing, in black ballpoint, is inspired by a headline: a suicide (of which there are now an estimated 35% more in Greece thanin 2010), a riot, demonstration, act of violence or despair, a story of poverty or deprivation.

“Whenever I read an article like that, I transfer the message to the medium,” Stefanos said. “By hacking the banknotes, I’m using a pan-European document to spread my imagery across borders.”

The artist began the project early last year when he realised he was being “bombarded daily by mass media about the collapse of the economy”.

He was struck, too, by the stylised, unreal representations of bridges, arches and gateways on euro notes – which, he felt, should better reflect the harsh realities of the period.

“So I fused the two,” he said. “I drew a mob running under the bridge of a €5 note, the grim reaper standing inside the temple of a €20 note, and a crowd invading a €50 note.”

Stefanos draws on “basically every note I can get my hands on. I use notes from my salary, family, friends, colleagues”. Once illustrated, he scans each one and uploads the result to his website, then puts the note back into circulation.

“It is quite a quick act,” he said, “and the drawings in most cases are small. I don’t know what happens to them afterwards; spending a note is an act of infinite possibilities and directions.”

But they are out there, doing their work. For Stefanos, eurozone policy, decided by an elite for the whole union, “may once have looked necessary to contain and recover from economic instability – but it is clearly not working”.

Stefanos feels the institutions’ objectives are “doomed to fail – that’s not a matter of an opinion, it is proved by the data. Enforcing austerity cannot be sustained any longer. The situation is fraught”.

Not all the the street art community approves of anti-austerity art. Alexandros Vasmoulakis, one of the first generation of painters to bring art to Athens’ streets, said he could “only look at the message, not the artistic talent – and I hate their message so much that I can’t get past that”.

Austerity art is all about “a blame game”, Vasmoulakis said. “It’s about putting the blame on Merkel and the IMF – on everyone except ourselves. And I hate that. We should stay in the EU; everthing else is uncertain – there is no plan. I hate that, and I hate the shallowness of thought in austerity art. If I could, I would take a brush and erase it all.”

But Iliana Fokianaki, who founded a pioneering non-profit Athens gallery, State of Concept, which showcases young contemporary artists and gives career advice to art graduates, said she appreciates the directness of the anti-austerity message – and agrees with it.

“Austerity doesn’t work,” she said. “That’s been proved everywhere. And what the institutions are doing to us – yes, we over-borrowed; yes, we had corrupt politicians – but is it really right to make the people pay like this?”

Fokianaki had no doubt about how she would vote on Sunday. “It’s a question of human dignity now,” she said. “We should get out of the euro. It may mean a year or so of suffering, but we’ll bounce back.”