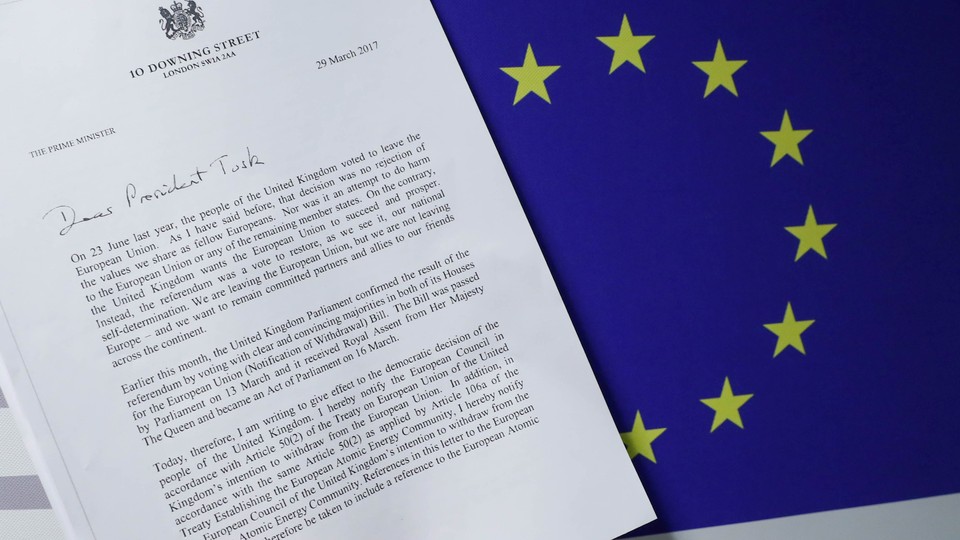

What did the U.K. government do on March 29?

The U.K.’s envoy to the European Union hand-delivered a letter from Prime Minister Theresa May to the office of the European Council president in Brussels, invoking Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty and formally beginning the process of talks over the U.K.’s separation from the European Union—the process that’s come to be known as Brexit.

How did we get here?

On June 23, 2016, Britons stunned Europe’s political establishment and voted 52 percent to 48 percent to leave the European Union. Prime Minister David Cameron, who had supported the U.K.’s continued membership in the bloc and who also wanted to give voters a voice on EU membership, resigned. After a brief period of political backstabbing, which saw all the favored successors to Cameron fail in their leadership bids, Theresa May, who had also supported remaining in the EU, emerged as the U.K.’s new prime minister. She pledged to respect the wishes of the public—dashing the expectations of those who’d hoped for a change of mind. She said she’d invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, the mechanism by which negotiations on the U.K.’s exit from the EU can begin, in March 2017. But while British politicians and policymakers argued with their European counterparts on what a future U.K.-EU relationship would look like, the U.K. High Court ruled last November the government does not have the authority to invoke Article 50, saying that authority lay with Parliament. The government appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed with the lower court’s ruling. After weeks of heated back-and-forth in Parliament, lawmakers voted on March 13 to give the government the authority to trigger Article 50. Three days later, the measure received royal assent from Queen Elizabeth II. On March 29, May invoked Article 50.

Is the separation immediate?

No. Article 50 gives the U.K. and the EU two years to reach an agreement on what Brexit will look like. The earliest we could have a deal is March 29, 2019, until which the U.K. remains a full EU member but won’t participate in decision-making.

But that two-year timeframe is seen as optimistic or, as the Financial Times puts it: “It may prove fiendishly hard or simply impossible to complete it all.” One unnamed senior EU figure told the FT: “Two years is unfeasible. The more you learn the more you bump into the complications and legal problems.” Indeed, the Telegraph reports that members of the European Parliament, who must vote on any final deal the EU reaches with the U.K., say that the U.K. must remain an EU member until 2022. Philip Hammond, the former U.K. foreign secretary who is now chancellor, warned last year that Brexit could take six years to complete.

As the BBC points out:

Unpicking 43 years of treaties and agreements covering thousands of different subjects was never going to be a straightforward task. It is further complicated by the fact that it has never been done before and negotiators will, to some extent, be making it up as they go along. The post-Brexit trade deal is likely to be the most complex part of the negotiation because it needs the unanimous approval of more than 30 national and regional parliaments across Europe, some of whom may want to hold referendums.

But Brexit has provisions in place for such an eventuality; the two-year schedule can be extended by unanimous consent of the European Council.

What happens next?

The U.K. government will first repeal the European Communities Act of 1972, the legislation that made accession to the EU possible, and then make EU law U.K. law. This would make business operations seamless even after the U.K. leaves the EU, but it would also allow U.K. lawmakers to repeal those aspects of EU law that they consider onerous or irrelevant.

Then begin the talks themselves, which are likely to be complicated: At issue is not only the future of EU-U.K. relations, but also the future of some 4 million people—3 million EU citizens and 1 million Britons—who live on either side of the English Channel. Here’s how Linda Kinstler described it in The Atlantic:

Brexit negotiations will come in two phases: the first, which begins on Wednesday, is a battle over what the divorce settlement between the U.K. and EU will look like. The two most important issues in those proceedings concern how much the U.K. will have to pay the EU upon leaving—current estimates are around $60 billion, though Brexit Secretary David Davis swore on Monday the sum would be “nothing like that.” The other issue is securing the rights of EU citizens living in the U.K., and U.K. citizens living in Europe. May has said she would like to reach an early agreement to secure the reciprocal rights of EU and U.K. citizens; arriving at such an agreement in the first few months of negotiations could be an easy win for both sides. In the meantime, the rights of EU citizens in the U.K. will indeed be used as “bargaining chips” in Brexit negotiations. Many families have already begun preparing to leave the country, fearing their loved ones may be denied the right to live or work in a post-Brexit Britain.

Much of the discussions so far have centered on whether it’ll be a “soft” Brexit or a “hard” Brexit. A “soft” Brexit would allow the U.K.’s relationship with the EU to remain mostly unchanged: in other words, with the U.K. having access to the single market, and with the free movement of EU citizens. A “hard” Brexit, on the other hand, would see the U.K. negotiators refusing to compromise on the unrestricted movement of EU citizens, thereby losing access to the single market. In reality, since immigration is one of the reasons Brexit occurred, a final settlement is likely to fall somewhere in between a “soft” and “hard” Brexit.

The EU will formally respond to May’s letter later this week by issuing draft guidelines on negotiations for the other 27 member states. A Brexit summit is scheduled for April 29, in which members will outline their negotiating positions. (Politico has a breakdown of what each of the 27 member states wants Brexit to look like.) Seventy-two percent of member states, comprising 65 percent of their populations, must agree on the eventual deal, which will then be ratified by legislatures in each of the 27 states. (No one said this would be easy.)

As Alex Stubb, the former premier of Finland, told the FT: “The U.K.’s negotiating hand is by definition weak. All the EU has to decide is the bill and the time of exit. The rest is altruism.”

Will Brexit hurt the U.K. economy?

It’s too soon to tell. The worst prognostications of Brexit didn’t materialize. The country is moving toward full employment and is growing more quickly than other major industrialized nations, but inflation is high and the pound is about 15 percent lower against the U.S. dollar.

Is Brexit reversible?

Although a considerable minority in the U.K. would like to think so, it would be political suicide in the U.K. to reconsider Brexit under the present political circumstances. The major criticisms many Britons had with EU membership—perceived loss of sovereignty and mass immigration from the bloc’s citizens—will persist unless something there’s a fundamental change of heart within the EU’s other 27 countries about what membership means to them. That won’t happen overnight: Polls in most EU countries show that most citizens see membership as a benefit. Practical considerations aside, May’s own remarks that “Brexit means Brexit” suggest the U.K. government is unlikely to revoke a decision made by a comfortable majority of its citizens. She reiterated those remarks Wednesday, telling Parliament: “This is an historic moment from which there can be no turning back.”

But never say never. John Kerr, the U.K. diplomat who wrote the text of Article 50, which May triggered Wednesday, told the House of Lords last month: “If, having looked into the abyss, we were to change our minds about withdrawal, we certainly could and no one in Brussels could stop us.” And Jean-Claude Juncker, the president of the European Commission, said last month he hopes “the day will come when the British re-enter the boat,” leaving open the possibility, however slim, for those Britons who want to remain part of the EU.

What happens to the U.K.?

This could be one of the most contentious issues in the wake of the Brexit announcement. The U.K., or United Kingdom, comprises England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. While England and Wales voted to leave the EU, Scotland and Northern Ireland voted overwhelmingly to remain. Brexit affects them, too. The Scottish government says it wants to secede from the U.K., calling for talks with the U.K. government on an independence referendum sometime between the fall of 2018 and the spring of 2019. The U.K. government says it won’t negotiate. May had previously said “now is not the time” for a Scottish referendum on independence. Scotland’s desired timetable for an independence referendum would fall within the two-year period of negotiations between the U.K. and the EU. A Scottish independence campaign run in parallel with the Brexit talks would considerably weaken the U.K. government’s hand.

In her letter to Donald Tusk, the president of the European Council, May wrote:

From the start and throughout the discussions, we will negotiate as one United Kingdom, taking due account of the specific interests of every nation and region of the UK as we do so. When it comes to the return of powers back to the United Kingdom, we will consult fully on which powers should reside in Westminster and which should be devolved to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. But it is the expectation of the Government that the outcome of this process will be a significant increase in the decision-making power of each devolved administration.

Then there is Northern Ireland. The Northern Irish border with the Republic of Ireland is the U.K.’s only land border with the EU. Critics of Brexit say that open borders between Northern Ireland and the Republic are a cornerstone of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, and any deal that doesn’t take this into account would imperil the peace deal. There have also been calls in Northern Ireland for a referendum on leaving the U.K. and joining the Republic of Ireland—though the prospect of that being successful are slim.

What happens to the EU?

As I wrote nine months ago, soon after the Brexit vote:

There were fears that Britain’s exit would energize Euroskeptics across the bloc. Indeed, polls in Denmark have suggested that the country would vote to leave if a referendum were held on membership (none is planned). Far-right parties across Europe rejoiced at the news from Britain Friday. Marine Le Pen, the head of the National Front in France, said on Twitter: “Victory for Freedom! As I have been asking for years, we must now have the same referendum in France and EU countries.” Similar sentiments were expressed by others across the bloc. Whether that translates to referenda in those countries and subsequent votes to leave is an unknown, however.

Since that time, however, the EU’s approval rating rose in its member states. Even in Denmark, the percentage of people who supported a Brexit-style referendum fell. Expected populist victories in elections across Europe have, at least for now, stalled.