Proximity flying—like many of life's challenging distractions, such as rodeo, fire-eating and meth—is not for everyone. Nor, as I suggest to elite wingsuit flier Ellen Brennan, is it the kind of recreation that anyone is likely to embrace on impulse.

"This," she replies, "is not something you can dabble in. This is not simply a sport. This is a different way of living your life."

We're standing just below the summit of Mont Blanc, at an elevation of over 12,000 feet. The peaks are wreathed in clouds, and the light snowfall is ruffled by southerly winds—conditions that mean the 26-year-old American is unable to opt, as she often does, for the quick way down. She points out the nearby ledge from which she normally jumps, in a suit cut from light paragliding material that gives her the appearance of a flying squirrel.

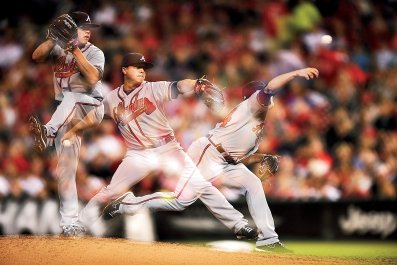

"For the first two seconds," she says, "there is this perfect quiet. That feeling is wonderful. Then you hear the rush of air. You fall for about [250 feet] before the suit inflates and starts flying. The more speed you have, the farther you're able to glide." When stepping off a cliff, she says, attention to wind and other climatic factors, some imperceptible to a novice, is vital. "People who don't pay attention to these things tend to get hurt. And most of them die."

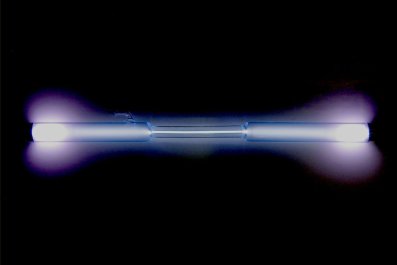

Brennan is one of the world's leading practitioners of a discipline that began less than 20 years ago. Design of the custom-made wingsuits, which typically cost around $2,500, has evolved to the point that experts can now fly between trees or rocks with a clearance of no more than a couple of feet on either side, at 120 miles per hour. Make a mistake, she concedes, and "the chances are that the emergency room is not going to be able to help you."

Proximity flying developed from base jumping: the art of free-fall parachuting in dangerous proximity to cliffs, buildings, or other elevated sites. Other mountain ranges, notably in Utah (where Brennan grew up), Colorado and Norway, are popular with wingsuit fliers, but no region attracts the elite practitioners more than this area of the Alps. Here, the terrain allows them to leap from high altitudes, then fly very low over elevated plateaus before emerging over much lower ground, at which point (after a flight time of around three minutes) it is possible to land safely with a parachute. Brennan moved here in 2012 with her boyfriend, Laurent Frat, another star proximity flier, so as to become intimately familiar with this unforgiving terrain.

The practice of wearing helmets equipped with cameras, then posting the resulting footage on YouTube, has encouraged some fliers to take ever more alarming risks. They have filmed themselves negotiating narrow ravines and rocketing through gaps in stone outcrops with an apparent recklessness that suggests their worst fear would be the words "Game Over" appearing on the skyline.

One of the most popular Internet clips, with over 3.5 million views, shows Jeb Corliss flying below the 1,053-foot Royal Gorge Bridge in Cañon City, Colorado, just as his best friend, Dwain Weston, was attempting a synchronized flight above it. Weston hit the bridge, smashing his body into pieces. Corliss landed soaked in his friend's blood, having been obliged to take evasive action because of what he described as "stuff" in the air. The first thing he saw on landing was a severed leg. What remained of Weston's lifeless body drifted gently down to Earth; the collision had caused his parachute to deploy.

Corliss, not a man plagued by self-doubt, became internationally famous after making illegal base jumps from buildings including the Eiffel Tower. Brennan, who is 5-foot-2, softly spoken and a qualified nurse, seems a less likely recruit to so hazardous a pastime. Even though upper body strength is an advantage in wingsuit flying, she was one of 16 elite fliers recently invited to an international competition in China, and regularly finishes in the top four in such mixed contests.

Fatality rates in the sport may not have reached those endured by some World War I allied aircraft squadrons, where death was so common as to inspire cracks such as "don't start any long books" and "don't buy any green bananas." But a 2012 study by Dr. Omer Mei-Den, a wingsuit enthusiast and assistant professor of orthopedics at the University of Colorado, indicated that 72 percent of fliers had witnessed death or serious injury, and 76 percent had experienced what they categorized as a "near miss." Known fatalities are running at about two dozen a year, a number that has been steadily increasing as more are attracted to the sport. Mark Sutton, the ex-Army officer who parachuted into the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics dressed as James Bond, died in a wingsuit accident close to Chamonix, France, last year. The average active career of a proximity flier has been estimated at six years, after which it is generally curtailed by death, injury or prudence.

The modern wingsuit was developed largely through the efforts of Loic Jean-Albert and Patrick de Gayardon, who met as members of the French skydiving team. The latter, who once predicted that arthritis would end his career, died in 1998 in Hawaii, while testing what he had assumed would be an improvement to his parachute. Jean-Albert, widely regarded as the father of proximity flying, retired after breaking his back in two places in 2007.

"You have a lot of friends who die," said Jean-Albert. "Skill does help, but skill can never eliminate risk."

In addition to that nightmarish flight in Colorado, the 38-year-old Jeb Corliss has had several other unenviable experiences, such as slamming into a rock face in 1999. I spoke to him at his home in Los Angeles.

"How many friends," I asked, "have you lost?"

"A lot," he says. "I'm not sure about the number. Of my close friends, I would say 50 percent."

Courting popularity has never been a priority for him. "If I die, I want that footage on TV the next day," he says.

"Why?"

"Because this is not chess. This is not backgammon. This is not…" he racks his brain for a yet more contemptible pastime, and finds one: "golf. This is dangerous. I believe that footage of fatalities is way more important than film of some guy flying across a beautiful meadow. What we are doing here is very important. I believe that flying is what evolution is about. Think of the squirrels.

"At the beginning, there were probably only a very few squirrels that even contemplated flying from tree to tree. The other squirrels thought they were crazy. I imagine hundreds of them died in the attempt. But then, in the end, one of them managed it. Now that, to me, is evolution. And now we are evolving, through technology and through skill. I liken what we're doing in proximity flying to the first animals that left the water. We are evolving and growing. And becoming stronger. What else is the purpose of life?

"Would you ask a bird, 'When are you going to give this up?' Any human being that has ever flown [in a wingsuit] and who knows that feeling, I don't believe that they are going to give it up."

On Facebook, Corliss once posted, "My death shall be violent, brutal, and there will be blood."

And he's OK with that. "I watched my grandmother die from cancer—in bed—and it was horrific. I can't imagine anything worse. What is important is how you live. Death is inevitable. I don't care how or where I die. Those details are not relevant. And who knows, death might just be one of the most beautiful things that we get to experience."

The next obvious goal for wingsuit enthusiasts is the ability to land without the benefit of a parachute. A few, including Corliss, have achieved this accidentally, but always at the cost of spending several months in plaster. A viral video on YouTube purports to show a young man landing on a lake in Northern Italy, but this footage was simulated. In May 2012, British stuntman Gary Connery jumped in a wingsuit from a helicopter at 2,400 feet above Oxfordshire and landed unscathed, using no parachute, on a 350-foot-by-45-foot-wide pile of cardboard boxes. Robert Pecnik asserts that, in 100 years' time, the safety and popularity of wingsuiting will be such that news of fatalities will raise no more public interest than a death in a motorcycle race.

On my last day in Chamonix, I meet Brennan in a café at the foot of Mont Blanc. Isa, her Australian shepherd puppy, is lying at her feet.

"Is it addictive?"

"Very. When you land, you have all these endorphins coursing through your body. The greater the risks you've taken, the more you feel that. And you establish close connections very quickly with people in the wingsuit community. I've tried dating people who don't jump. It never works."

Proximity fliers, in common with goalkeepers, infantrymen and others whose lives involve the regular anticipation of possible catastrophe, tend to be superstitious. Brennan tells me she used to carry a lucky penny when she jumped. "I stopped doing that," she says, "because I started to wonder how I would react if I ever lost it."

"Is there anything that would stop you from flying? Children?"

"I don't think that I could stop doing what makes me happy. Not entirely. If I had children I probably would not proximity-fly. I would do nice scenic flights. But quit altogether? I honestly don't think I could. Even now, if I don't jump for a few weeks, I become…a person that I don't like."

"Is there anybody telling you to stop?"

"My mom. She hates it. But then don't you think this all comes down to the question of what you want from your life? Do you want to go to school, leave, find a husband, buy a house that is way too big, buy too many cars that are way too big, make babies, live in debt, work your ass off, never get out of that hole and exist knowing that this is all that you'll ever have, apart from maybe two weeks' vacation in Florida every summer? Because that's not what I want. I want to see the world. I want to do things that people tell me I can't do. And that domestic grind, to me, is not life. And personally…" she pauses, as if searching for a way to justify her perilous vocation in a phrase, "I want to live."