On a day the country reflects

upon the past, Globe Books offers an exciting glimpse into the

future, with new poems and stories from some of the most dynamic emerging

Indigenous writers at work today

Elegy

by Shannon Webb-Campbell

I am an edge walker

I am a frozen seabird dumped on a beach

I am a beach walker who came upon a heap of bloodied turrs

I am a murre who is graceless on land, but swims like a fish

I once plunged 600 feet deep into the water before I was shot down mid-flight

I am the only hunter allowed to kill seabirds around here

I am the land weeping, having to bear witness

I am an interpretive site where "the Beothuk used to roam"

I live on a rez where the only in is the only out

I can't find my grandmothers out here on the land

I am a verdict

I am a taddler who speaks to newspapers

I am a country that questions the nature of abuse

I am a failed legal system

I am a medicine woman who lost her medicines

I am a stolen prayer

I am a blurred vision

I am huffing gas instead of oxygen

I am turning a blind eye

I am jealousy's root system

I am a wounded healer

I am dishonouring my father's years of sobriety

I am an empty bottle under the sink

I am ashamed of my red skin

I am swallowing all my tears that now live in my body

I am a woman unprotected like our waterways

I am a teenage girl found dead in a worn out Bullet For My Valentine t-shirt

I am a sister in Swan River who ran out to pick up a cheque and never came home

I am just starting puberty and missed my best friend's birthday party because I'm in a flowerbed on Garden Hill First Nation

I was shot by my ex-boyfriend in a plaza, who killed my fiancé and then himself

I am a body left to rot in a dumpster, on a stretch of highway, on abandoned back road

I am a mother who took my husband's bullet in Hermitage

I am a double murder suicide

I am Innu woman, heading to work in Voisey's Bay and mixed drinks with the wrong crowd

I am running naked, screaming for help because a man tried to drown me

I am not protected by law because I am a buckskin sex worker

I lay under the weight of a man who checked my pulse after he raped and choked me

I am dragged off to meet the northern lights

I am the children with sores and rashes who are poisoned by the drinking water

I am a boreal river where we can no longer swim

Author's note: All violence against women roots in violence against the earth. Elegy doesn't lament the dead, its poetics embody the land and unspeakable trauma of thousands of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and Two-Spirits. Written in collective first person, Elegy witnesses the colonial violence of thousands of silenced voices.

Shannon Webb-Campbell is a mixed Indigenous (Mi'kmaq)-settler poet, writer and critic. She is the author of Still No Word (Breakwater, 2015) and Who Took My Sister? (BookThug, 2018).

Danielle Daniel, a Métis writer, artist and illustrator, will publish her second picture book, Once in a Blue Moon, this fall. Her first picture book, Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox, won the Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Award, and she is also the author of a memoir, The Dependent.

Danielle Daniel/Groundwood Books

Around the Riverbend

by Alicia Elliott

Blair never seemed to hear the microwave beeping – not even when she was three feet away, feet propped on the kitchen table as she painted her toenails a delicate pink.

At first, Aunt Rachel thought Blair's ears were to blame; she did sit alarmingly close to the speakers at pow-wows, after all. But a free hearing test revealed the speakers had little to no effect. Her problem was not and had never been her hearing. She could hear the microwave perfectly. Her problem was willful blindness. Or perhaps in this case, willful deafness – the most teenage of ailments. Blair simply chose to ignore what she didn't want to hear.

Before this year Blair had been mostly ignored. She'd watched each of her friends fall victim to the onslaught of puberty: entering with sweatshirts and pudgy cheeks and emerging with breasts and blackheads and skin-tight leggings that shouted every detail to the world. Blair's chest remained stubbornly flat, her hips defiantly narrow. When she walked down the street in a pair of shorts it was unremarkable. When her friends walked down the street in shorts it was an event: there were hoots and hollers from windows, beeps from rusted out rez cars, deep frowns from disapproving elders. There was something almost insidious about puberty – the way it slammed shut the door to childhood, never be reopened, and shoved you face-first into this strange place called "womanhood."

Then, on the eve of her thirteenth birthday, puberty came for Blair. It molded her chest into tits, her butt into an ass, carved cheekbones out of her face. She tried to stifle her body with oversized shirts and poor posture but it was no use. Those rebellious curves were still there, pushing out from the fabric, demanding their due.

Aunt Rachel tried to explain to Blair how her period connected her to the earth, the moon; how she was one in a line of women that could be traced all the way back to Sky Woman, the mother of our nations. She was trying to be nice, Blair knew, but it was too late. She saw the way men looked at her now. Women, too. As if she were land to claim, a rival to kill. She'd already resigned herself to the idea that her body wasn't hers: just flesh and bone on extended loan, bound to be collected by some man sooner or later.

***

That summer Blair got a job selling 50/50 tickets at the Speedway with her best friend Sam. She didn't need a resume. The boss, Helen, looked her up and down and told her she started Friday.

"Just dress sexy," Helen said.

"Um, I don't think I have—"

"Trust me, we'll make it work."

And they did. Apparently anything could be made sexy when you're a thirteen-year-old girl. Helen would roll up Blair's shorts if they were too long, or strategically tie up Blair's shirts to show off her flat stomach. She even kept an emergency stash of lip gloss at the concession stand so Blair could do touch-ups whenever dirt careened from the racetrack onto her sticky lips, ruining the underage bombshell effect. Blair wondered how many other girls' lips were lacquered with that same pink gloss. It smelled like cotton candy.

The customers, mostly older white men, would stare at her long tan limbs and smile at her like they knew something she didn't. It bothered Blair, but the other 50/50 girls had no problems. They divided themselves into two selves: the one that smiled sweetly to these men's faces and laughed at their bad jokes; and the one that grimaced as soon as their backs were turned, collecting their reactions like baseball cards to trade with the other girls at the food stand. It became a game: the girls would tell their stories about these desperate old men, and at the end of the night, the girl who had the grossest story – the one that made the other girls groan and squirm with unease – was the girl that won. Most of the time the stories were pretty tame. A wink here, a sudden, unsolicited grab of your hand there.

But one time a regular named Chuck tried to follow Blair into the porta potty. He was so close she could smell the damp of his deodorant. She turned fast and looked up at him. His eyes were entirely black. He looked like he was possessed. Blair was too shocked to scream, to move. She just stood there, mouth open, waiting for whatever came next.

Chuck laughed. "The look on your face!" he hooted as he stumbled back to the stands.

Blair stayed in the porta potty until her breathing was normal again.

"What happened to you?" Sam asked. Blair told her.

"Ever gross! You gotta tell the girls. You'll totally win tonight."

"Should I tell Helen?"

"No point. As long as they're spending money she don't care. Anyway, that's the job, innit? Looking cute to make dirty old men buy tickets from us?"

Sam was right. That was the job. But after the races, after the eyes and the hands and "sweeties" and "dolls," after Chuck and the porta potty, as she stared at the limp bills in her hand, she felt how little value they actually had. What's more, she sensed that her own value was somehow tied up in the whole transaction, only instead of watching it grow week by week like the small stash of bills in her sock drawer, she felt it slowly diminishing, as if it were being pressed hard against a sieve.

Still, Blair showed up promptly at 7 p.m. every Friday night, shorts hiked up, lips smeared shiny and pink.

Author's note: This is an excerpt from a story called Around the Riverbend, which will appear in the short-story collection I hope I'll finish this decade. It's an artistic response to the ways misogyny and colonialism uphold and reinforce one another, trying to tear down and reshape Indigenous girls like Blair.

Alicia Elliott is a Tuscarora writer living in Brantford, Ont. She recently won gold in the Essays category at the National Magazine Awards.

Danielle Daniel/Groundwood Books

Olympia, Washington

by Gwen Benaway

for Dylan

the last time I'm with you

in our small love, you still want me

enough to play some sad song

on your guitar in the sunroom

as your plants grow beside us

I watch you unfold in night

momentary bloom, you are beautiful

as no other boy can ever be again.

you say the plants are mediating

they reach for the distant light

no matter anything, even so small

at their roots but they still

grow green, lift up towards

sunlight as if they're sentient

in their thirst for what keeps

them alive, longing for

a chance to become whole –

just like me, a trans girl

I reach for a strange light

I never find. I want nothing

more than what sustains me.

if you had looked at me

with clear eyes, you'd see my heart

bend to you, lifting to your face,

asking to be a girl with a boy,

not a curiosity but a possibility,

this is why I tried to hold your hand

when you left me.

Author's note: I want to show the romantic space between trans girls and cis boys, the softness between our bodies and complexities of navigating the weight of social pressure, transphobia and our inequalities in power. To humanize, complicate and celebrate trans girls and cis boys in love, even when it's painful.

Gwen Benaway is a trans-girl poet of Anishinaabe and Métis descent who has published two collections of poetry, Ceremonies for the Dead and Passage, and will be publishing her third collection, Holy Wild, with BookThug in 2018.

Danielle Daniel/Groundwood Books

full metal oji-cree

by Joshua Whitehead

this is the transsensorium

there are indo-robo-women fighting cowboys on the frontier

& winning finally

premodern is a foundation for the postmodern

wintermute, tessier-ashpool, armitage

theyve revived us via neuromancy

but i am the necromancer

when i tell my mother i need kin

she sends me ten

weve all been subjected to zombie imperialism

dying in the sprawl of night city winnipeg

your world feels ontological

the nexus of adaptation & appropriation

old abelardlindsay|abrahamlincoln told me

that i was too loyal to my gene-line

that the point is that "we" live

i tell him there is no 'i' in that 'we'

—never was

no room for white superiority in indigeneity

we were surviving

we are surviving

ive nullified your terra myths

i am more than props & backdrops

i am terrae fillius,

u: neocoloumbus

i am terra full[ofus]

(do indians in space become settlers too[questionmark])

now is our time

to show off our cooper skin, shimmer

free-fall headdress & robomoccasins

this pink & white gridwork is my technobeadwork

our (ab)use value has increased

i am the punk in amer[in]cyber[dian]

the posthuman is innately indian

when novelty is horrific

i tell you: this is the extraterraium

were not mothers, were police

the prehuman becomes the precursor to (rez)urrect

the posthuman in the transhuman

so fuck you

well survive this too

like the cat ive nine times to die

like the woman i ask:

how can you live so large

and leave so little for the rest of us[questionmark]

ive outlived colonial virology

slayed zombie imperialism

us indians sure are some bad ass biopunks

wearesurvivingthrivingdyingtogetitright

Author's note: This is an excerpt from a longer poem from my forthcoming collection, full-metal indigiqueer, a book of poetry invested in revisionism. The text features the pro(1,0)ZOA, a cybernetic Two-Spirit trickster I invented from the many stories I heard and read (creation through to cyber/biopunk). The goal of ZOA is to infect colonial, pop and canonical texts (from The Faerie Queene to Lana Del Rey) in order to recentre Indigiqueer/Two-Spirit and Indigenous livelihoods.

Joshua Whitehead is an Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit storyteller from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1). His debut book of poetry, full-metal indigiqueer, will be published by Talonbooks this fall.

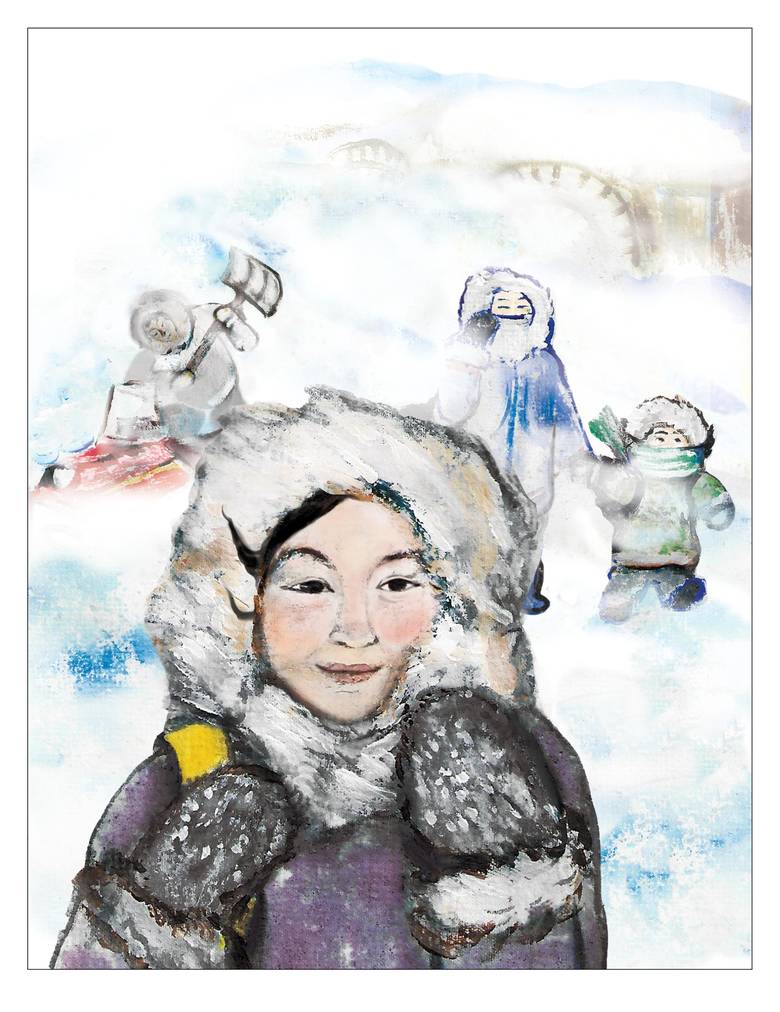

Only in My Hometown is a forthcoming debut picture book written by Angnakuluk Friesen, who grew up and lives in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, and illustrated by Ippiksaut Friesen, an Inuk also from Rankin Inlet. She studied at the Emily Carr University of Art and Design, where she majored in animation. Her art focuses on Inuit communities. She currently lives in Iqaluit. Only in My Hometown, about what it’s like to come of age in an Inuit community, will be published by Groundwood Books in September.

Ippiksaut Friesen/Groundwood Books

Moon of the Crusted Snow

By Waubgeshig Rice

The entire main floor smelled like the moose roast that was in the oven when Evan walked in to the house. His mother Patricia was sitting at the desk on the far side of the living room. She rapped the black computer mouse loudly on the desktop. "The god damn internet isn't working!" she announced, without turning around. "Come here, Ev. Fix this for me!"

"Okay, just wait then," her son replied. "Where do you want me to put these?" He held up the clear bags of moose meat. She turned to look and smiled slightly, pushing her cheeks into the bottom of her glasses. "Ever the good son!" she proclaimed. "Just put that on the counter, and I'll take them downstairs to the freezer later. I gotta rearrange the other one your dad just got."

Evan set down the meat on the scarred white countertop in the kitchen. He could navigate this house with his eyes closed, and every step through each room was like muscle memory. The heavy oak dinner table anchored the house, the centre of so much family history. He went back into the living room to assist his mother, walking past the soft, black leather couch, loveseat, and armchair set that furnished the room, and wished they were there when he was a kid. They were all so comfortable, and they still smelled new.

He stood behind her as she slammed the black mouse again in frustration. "What the hell is wrong with this? I gotta check my email!" Evan smirked, knowing that was a minor fib. She was hooked on playing in online euchre tournaments. There wasn't any money in it, but there was international glory and she liked the idea of playing her favourite game against people from all over the continent. "God damn it!" she repeated.

"How long has it been out?" he asked.

"Just since yesterday afternoon. I was chatting with your sister online and then it crashed. Then I tried to text her and that didn't work either."

Evan raised his right eyebrow. "Your TV's not working either, eh?"

"No, not since around the same time. I thought all these new dishes and towers and stuff were supposed to be better!"

"Well, I guess it's not all totally reliable all the way up here," he assured her and himself. "All this stuff doesn't go out as much as it used to."

"Yeah, I guess so."

"Now you have more time to make supper. Maybe we'll actually eat on time for once!" She elbowed him in the gut. "Oh you shut up," she huffed in response, as she stood up to go to the kitchen.

The truth is, Evan thought, these things do work better than they used to. High speed internet access had been in the community for barely a year. It connected to servers in the south via satellite, but used a different system than the television providers. Each home was responsible for signing up and paying for its own TV and cellphone service, but that was all with the same company that seemed to have a monopoly in the north. Internet service was provided by the band itself, using separate infrastructure.

Still, the fact that all three services were down at once made Evan uneasy.

A sharp cacophony of metal pots and pans crashing together came from the kitchen, and Evan realized he was staring at the stale, white computer screen that read "Can't connect to server". He blinked hard and gave his head a little shake.

"I'm gonna head back outside to see dad," he said.

Outside, Dan had begun to strip the hide of its fur. The son took his spot beside his father again. "What you thinking about doing with this one?" Evan asked.

"I dunno, maybe your mom can make something of it." Patricia usually made moccasins and sold them to trading posts and souvenir shops throughout the north. It was good extra money.

They stood quietly again. That comfortable, easy, important silence between a father and a son fell upon them. Evan pulled out his pack of cigarettes once more, and so did Dan. They took long, soothing drags on their smokes, staring into the hide and occasionally into the forested horizon.

Without turning, Dan said, "I had a dream last night." Evan's head turned slowly in his father's direction. "It was night. It was cold, kinda like this time of year. But it was the springtime. I dunno how I could tell because it was so dark, but I just knew that it was.

"I was walking through the bush. I remember I had my shotgun over my shoulder. I had a backpack on too. I dunno why or what was in it," his sentences came out slowly, with a precise rhythm. Evan dragged on his cigarette again, transfixed by his father's unusual candid speech.

"There was this little hill in the distance. I could only see it because it looked like there was something burning on the other side. There was this orange glow. It was pretty weird. It wasn't anyplace that I recognized. Nowhere around here, anyways. So I kept walking towards the hill. The light on the other side got brighter. I knew it was a big fire, the closer I got."

Evan couldn't remember the last time his father had spoken so much at once. He wasn't known as a storyteller or a talented orator. He never talks about dreams, Evan thought.

Dan continued with his short, steady delivery. "As I went up that hill, I started to see the flames. They were so high. Then I heard it. It roared, kinda like the rapids down the river. It was popping and cracking real loud. And then I got to the top."

Evan's face tightened, and the hair stood at the back of his neck.

"The whole field on the other side of that hill was on fire. I couldn't see nothing in that field except fire. But it wasn't spreading. Then I looked around and seen a bunch of you guys standing and looking at it. It was you, your brother Cam, Izzy, some of your buddies, and even the chief, Terry. There were a bunch more too, but I couldn't tell who they were because they were too far away. You were all spread out, just looking at the fire."

Evan inhaled deeply. His cigarette had burned down to the filter between his fingers, singeing the orange paper. Dan stared forward as he spoke.

"Everyone was wearing hunting gear and had their guns in their hands. But no one had any orange on, like right now. And when I looked closer at your face, you looked real skinny. Cam too. And the other guys looked weak. It was pretty weird.

"Then I understood what was going on. We put the burn on to try to get some moose in. I can't remember the last time we had to do that around here. But everyone in my dream must have been hungry. No one was saying nothing. I looked over at you," he paused and turned to look at Evan.

"You looked at me. You looked scared. And that's when I woke up."

Author's note: This is an excerpt from my forthcoming novel, Moon of the Crusted Snow. I wanted to explore how a so-called "postapocalyptic" story would unfold on a reserve. I believe one community's collapse is another community's opportunity for a new beginning, and that's what I tried to portray here. It's a look at posturban life through an Anishinaabe lens.

Waubgeshig Rice grew up in Wasauksing First Nation and is the author of a short-story collection and a novel. He currently lives in Ottawa with his wife and son, where he works as a multiplatform journalist for CBC Ottawa.

Home (not ours)

by Carleigh Baker

A spectrum of intimacy, all of it strange. Strangers who spent months getting to know each other through stilted Skype calls come together for twenty-one days in the "wilderness." I use quotes because I don't like the word wilderness anymore, it feels like other-ing the land. In order for there to be wilderness, there has to be civilization. This is a binary I don't think I'm onboard with anymore, but I haven't quite figured it out. But okay, here we are, in an intimate relationship with the land and each other. Out of our "civilized" comfort zone.

The day after four of the six canoes capsized, including mine, I wake up so fearful. I don't want to talk about it; talk will just swirl the fear around. For a little while longer the tent is a fortress, so I edge my sleeping bag closer and closer to Tony's, until I'm practically spooning him. When he wakes up, he presses back into me.

"Is this okay?" I whisper, stupidly worried that he might misunderstand my intention as something romantic. Beyond a hug now and then, my friends and I aren't very touchy. It isn't a comfort I've ever associated with friendship, and now I wonder why.

"Yep," he mumbles. We lie like that, filtered yellow light in the tent, the impression of his warmth through my mummy bag so tangible, until the call comes to get up. Since yesterday was so brutal, we got to sleep an hour later than usual.

"As soon as today starts, I have to admit that yesterday happened," I say.

"Yesterday did happen," Tony says.

To my left, Alecia wakes up, and I hug them both to me, trying to be some kind of comforting, nurturing force. I don't know how people do it.

"We got this," Tony says

"We got this," Alecia says

We got this.

And then there's no choice but to start the day. Unzip that tent, somebody.

***

Everything that was wet is now frozen. I peel my long underwear off a bush, and it stands up on its own. It's some kind of man-made material that didn't dry anywhere near as quickly as the Merino wool. There's weak laughter about the frozen clothes as people ready their game faces for the day. We round up our gear and re-hang everything around the breakfast fire, but it's with a sense of defeat. This stuff is going back into our bags wet, for who knows how long. A pair of my wool socks are frozen stiff as well. I consider leaving them on the beach, a sad find for the next travellers who pass this way. But I shove them in a plastic bag, along with the base layer, and shove the plastic bag in the mesh outer pocket on my backpack.

"Can I take your picture?" Callan asks. Unlike me, he's an experienced tripper, and has been in many situations like this before. Yesterday, in the middle of the chaos, he was a rock. As we gathered firewood, he circulated with this beautiful calm, asking how we were doing in a way that zoomed me back into my cold, wet body for a few seconds. But, like all of us, he's here to get work done. This is a documentary. The cameras that circulated yesterday got us all at our worst. Or maybe at our best, in some ways. That feels like something a person in a documentary would say. After a night's sleep, I can admit that the capsize will provide good fodder for my writing as well.

"Come down here with me." He leads me to the river's edge. Since we had to get out of the water immediately yesterday, we're camped on a thin rocky bank beside a cliff, within sight of the ledges that caused all the trouble. First one capsized the boat, and I took the second one clinging to the overturned canoe.

"Face the river," Callan says. It looks more menacing than it has for the last few days – boiling and full of whitewater. The roar is louder. "Now look back at me and just feel whatever you feel right now."

His direction sparks inside my body – the corners of my mouth contract, my chest tightens, shoulders pull in. Eyes squint. Not going to make a very flattering shot, I think, as the shutter clicks.

Callan gives me a hug. "I'm a little jealous that you can access your emotions so easily," he says. "I can't do that."

"I wish I had more control over them," I say, for the millionth time since the trip started. Probably the billionth time in my life. It's something that I say for other people's benefit, so they know I'm trying to be less of an emotional burden.

"It's a gift," Callan says. "Don't sell yourself short."

"Okay." I'm embarrassed. It's uncomfortable to be studied so closely.

Callan moves off to get some more portraits, and I give the river the finger.

Author's note: This is an excerpt from a mixed genre memoir/novel-in-progress. In 2015, I paddled the Peel River in the Yukon/Northwest Territories, along with five other artists and a documentary film crew. This river system is one of the last undeveloped watersheds left in Canada. The trip taught me about community, accountability and the vital importance of Indigenous land sovereignty.

Carleigh Baker is a Métis-Icelandic writer. Her first collection of short stories, Bad Endings, was published by Anvil Press earlier this year and her work was selected for the Journey Prize Anthology in 2016. Her fiction and essays have appeared in publications across Canada and she is a regular contributor to The Globe and Mail. She lives in Vancouver.