A freshly elected Greek radical leftwing prime minister takes on Europe’s institutions. He wants to change the way things are done. He is astutely aware of the proud nationalism that runs through Greece’s history. He appeals to those who have felt downtrodden. He has misgivings about the west in general, liberal economics in particular, and wants people to believe he can turn elsewhere – occasionally, to Moscow. He has read Trotsky and Gramsci. He likes to illustrate his nonconformism in the way he dresses.

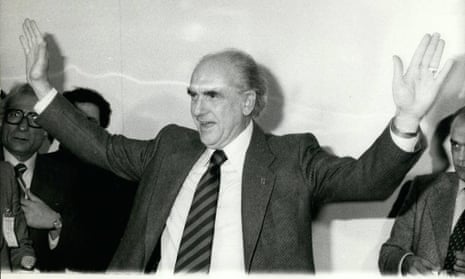

Remind you of anyone? Yes, it could be Alexis Tsipras. But this also fits the profile of Andreas Papandreou. In 1981, the leader of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (Pasok) came to power in Greece, and opened an unexpected chapter in the country’s political life as well as in the evolution of Europe.

Just like Tsipras, Papandreou didn’t like ties (he preferred turtlenecks under his jacket). And just like Tsipras, he came to office wanting to reverse the way his rightwing predecessor had negotiated with Brussels. In 1981, Greece had just joined Europe. Back then, it wasn’t the European Union but the European Economic Community, and Papandreou was vociferous in describing it as a threat to Greek sovereignty, a force dictating unequal terms, a neocolonial enterprise working for the “economic oligarchy”.

With time, however, all of this was pushed aside. After his election, Papandreou started to see the strategic advantage of sticking to the European club. He became an absolute master of the art of extracting maximum economic aid from European funds.

It is, of course, an imperfect parallel. Not least because no one knows quite how the current Greek crisis will unfold. One major difference is that in the 1970s and 1980s Europe was going through a burst of optimism and expansion. Brussels set up structural funds that many of its new, poorer members profited immensely from. That is a far cry from the austerity measures and the growing Euroscepticism of today.

But some similarities are striking, and lessons might be drawn from the past. In 1981, just like today, Europe faced in Greece two existential challenges: how to harness democracy, and how to prevent geopolitical instability. Papandreou saw this and reacted accordingly.

It is hard to overstate the link between Greece’s democratisation and the European project. Greece formally applied to join the European Economic Community in 1975, less than a year after the fall of its military dictatorship. Greece was small and poor and its political clientelism was notorious. Not everyone wanted it to be let in. What helped, though, is that its agriculture, unlike Spain’s, posed no threat to French farmers – so the then French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing made sure Greece entered at a much faster pace than Spain and Portugal.

Mediterranean Europe’s transition to democracy was a remarkable development. By the 1980s, Greece, Spain and Portugal had not only undergone a peaceful conversion to parliamentary democracy, but seen genuine social progress. This was helped by the fact that socialist parties, previously clandestine and ostentatiously anti-capitalist, became the dominant political forces, governing in effect from the centre. For Greece, membership amounted to another Marshall plan: funds flooded in, boosting GDP. A lot of the money may have been squandered by corruption and networking, but anyone could see the improvements, for example in infrastructure.

It was a strategic move for both Europe and Greece – a country that lies at the crossroads of many worlds: the Balkans, the Slavic realm, the Middle East and the Mediterranean. Papandreou could see the advantages of breaking out of isolation. Security considerations have shaped Greece’s European policies for decades. Tensions with Turkey over Cyprus and the Aegean played a central role in the 1970s, and have not gone away.

The looming question today is whether Greece can play a stabilising role in the unfinished business of bringing the whole of the Balkans into the European project, or whether it will turn into a foothold for Russian influence. This matters because the Balkans remain one of Europe’s great unsolved puzzles, a source of possible further disruptions.

Greece has had qualms in the past about harnessing itself to western policies. Tsipras has flirted with Vladimir Putin, just as Papandreou enjoyed occasional closeness with Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi at a time when the rest of Europe and the US shunned him. In the 1990s, Greece expressed a degree of sympathy for Slobodan Milosevic’s Serbia during the Balkan wars and opposed Kosovo’s drive for independence. To this day, Greece refuses to call one of its neighbouring states by its name, Macedonia. For many reasons, the Balkans remain unpredictable, and the way Greece positions itself will play a role in the ongoing geopolitical quagmire.

So the Greek crisis should not be looked at solely through the lens of economic statistics: austerity, debt levels and pensions. The underlying questions are: can Europe still be seen in Greece as an anchor for a relatively young democracy? Ahead of Sunday’s referendum, some of the yes demonstrators in Athens seem to think so. And could Greece, located on the continent’s unstable, exposed south-eastern flank, still contribute to a European project in dire need of rejuvenation, not the kind of bashing that in the end weakens everyone?

In the 1980s, Papandreou, a charismatic orator, made choices that put aside radical ideology and confrontational tactics. He did much to counter Greek national reflexes of victimhood, however justified, and forged ahead with constructive policies. In doing so, he helped lessen the legacy of Greece’s civil war, a trauma that Tsipras has played on in his many references to the second world war and its aftermath.

Instead of being the avenger of the Greek left, Papandreou opted for pragmatism. Instead of radical rhetoric, he espoused the prudence that helped pull his nation out of its troubled past. His could be a story from a forgotten era. Or not?