It is a lunchbox staple so ubiquitous as to have become mundane. But the apple we know today is the fruit of an extraordinary journey, researchers have revealed.

Scientists studying the genetics of the humble apple have unpicked how the cultivated species emerged as traders travelled back and forth along the Silk Road – ancient routes running from the far east to the Mediterranean sea.

Published in the journal Nature Communications by researchers from the US and China, the study focuses on genetic data from 117 different varieties of apple. These encompassed 24 species ranging from wild apples found in North America and China to domestic apples including ancient, cultivated varieties as well as those found in our supermarkets.

By comparing the genomes of the different varieties and the characteristics of their fruit, the team were able to reconstruct the apple family tree and explore the fruit’s evolutionary history.

“Our research is the first whole genome level analysis about apples’ evolutionary history,” said Yang Bai, co-author of the research from the Boyce Thompson Institute at Cornell University.

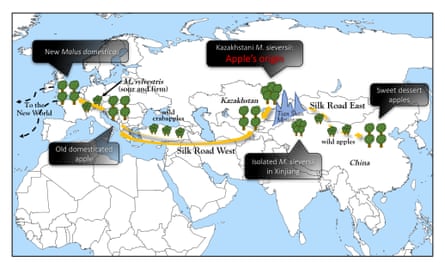

The apples we know today, varieties of the species Malus domestica, have long been known to have descended from a species of wild apple from central Asia, known as Malus sieversii.

The new study confirms this, but also goes further. While Malus sieversii grows in both Kazakhstan and Xinjiang in north-west China, the team found that apples from the two areas are distinct, with those in Xinjiang never cultivated.

“Those apples are not getting involved in any of the domestic apples – they are a lost jewel hidden there in the Xinjiang area,” said Bai.

The team say the finding suggests that modern cultivated apples have their roots in the trees of Kazakhstan, growing to the west of the “Heavenly Mountains” – the Tian Shan.

Previous research has also suggested that these apples were brought westward by traders along the Silk Road. But the trees which took root, either from deliberate planting or from discarded apple cores, did not grow in isolation: they cross-pollinated with wild species in the area. In particular, researchers have said, the European crabapple, whose small, sharp-tasting fruit is used to make cider.

The new study, says Bai, suggests the resulting apples were large – a trait passed on from Malus sieversii – while the crabapple contribution appears to have made the apples firm and tasty.

Indeed the new research suggests about 46% of the genome of modern, domestic apples is likely passed down from M. sieversii plants from Kazakhstan, with 21% from the European crabapple and 33% from uncertain sources. As the trees were subsequently selected and bred by humans, the apples’ traits continued to be refined for larger size, better flavour and firmness.

But the apple’s journey was far from one-way. The genetic study revealed that apples from Kazakhstan were also carried eastward – along the way they, too, picked up contributions from wild apples, resulting in the smaller, softer, sweeter fruits that are typical of Chinese dessert apples. “The traders go across the Eurasian continent both ways,” said Bai. “They spread those ancestral seeds along their way.”

And the story of the apple continues to blossom. According to the researchers, the size of apples could be greatly increased by further breeding, while the discovery of the genetically distinct Malus sieversii apples in Xinjiang could help to improve modern varieties, including by potentially offering a genetic resource for disease resistance. “Researchers definitely can find a lot of useful traits in those [apples],” said Bai.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion