Congress Prepares to Launch a New Era in Education Policy

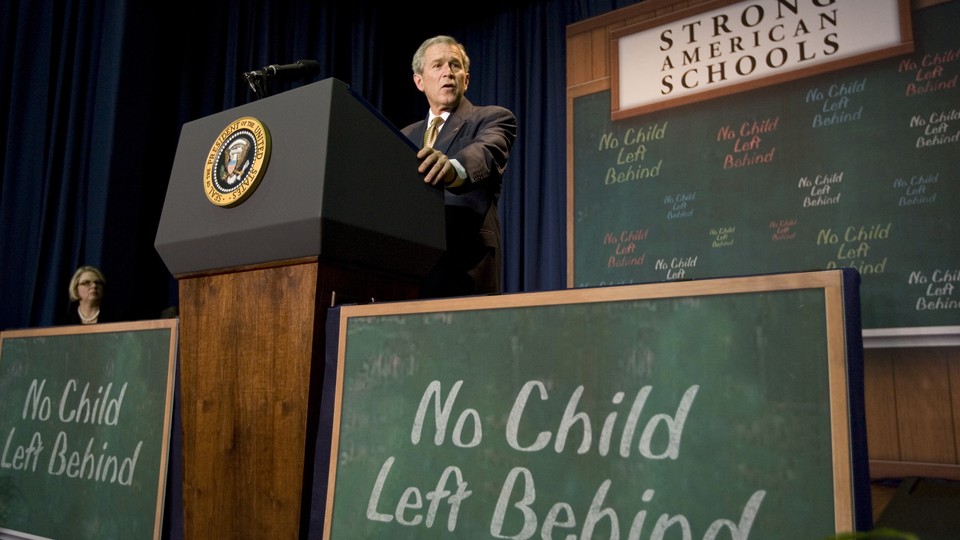

A bipartisan agreement to replace George W. Bush’s signature No Child Left Behind law could pass next month.

In the next few weeks, a bipartisan majority in Congress is likely to pass a law that, in various ways, repudiates the education legacies of both the Bush and Obama presidencies.

House and Senate negotiators last week agreed to a legislative framework replacing George W. Bush’s signature No Child Left Behind law, a landmark reform of K-12 education placing strict federal requirements on states and schools that proved unworkable over time and led to a culture of testing that drew criticism from liberals and conservatives alike. While some federal benchmarks for accountability will remain in place, the new bill gives much more latitude to the states and restricts the ability of the secretary of education to punish or reward them based on their progress.

The overhaul is years in the making—Congress has been due to reauthorize the underlying Elementary and Secondary Education Act since 2007. And in the absence of action on Capitol Hill, the Department of Education has amassed even greater power by negotiating waivers with 42 of the 50 states to exempt them from the law’s sanctions, which included the potential closure of schools. Ultimately, the mounting frustration both with the original law and the waiver system that took its place propelled an alliance among Republicans, Democrats, and even the teachers unions that have battled the leadership of both parties over the years.

The final bill is still being drafted, but a House-Senate conference committee approved its framework in an overwhelming vote—of the 40-member panel, only Senator Rand Paul voted against it. Despite concerns about the restrictions the new law would place on the secretary of education, the White House “is pleased with the framework,” said Roberto Rodríguez, an education adviser on Obama’s Domestic Policy Council. Advisers and advocates in both parties described the bill as a genuine compromise between a bipartisan plan that passed the Senate and a more conservative House bill that would have eviscerated the federal role in education policy and shifted more resources away from needy schools.

Praise has come from unlikely corners.

“It corrects what the federal government has gotten wrong in terms of policy, but it maintains what the federal government has right in terms of policy,” Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, told me in a phone interview. “Is it perfect? Of course not. But by doing those two things simultaneously, it’s a very big step.”

Unions have railed against the mandates for teacher evaluations that the Obama administration required in exchange for No Child Left Behind waivers, calling them an excuse to scapegoat educators. While the new law would keep in place requirements for yearly testing of students in grades three through eight and once in high school, it scraps the federal evaluation requirement. And instead of mandating that schools demonstrate “adequate yearly progress” through test scores, the government would allow states to submit their own plan for accountability that could take into account factors beyond testing.

“Our bipartisan agreement will reduce reliance on high-stakes testing, so students and teachers can spend less time on test prep and more time on learning,” said Senator Patty Murray, the lead Democratic negotiator.

Democrats successfully pushed for what they called “federal guardrails,” or provisions that allow Washington to intervene if states don’t address schools performing in the lowest 5 percent or where more than one-third of students drop out before graduation. States will also be required to report data on the performance of key subgroups to ensure that disadvantaged students aren’t being ignored, and the law would cap at 1 percent the proportion of students with disabilities who could be excluded from the main state assessments.

“This is not an up-and-down conservative triumph,” said Frederick Hess, the director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute. “The federal machinery of NCLB, while largely defanged, is still in place. From the administration perspective, that’s a win. They get to keep that machinery and the head-nodding toward Washington.”

Yet Hess said that overall, Republicans got 75 to 80 percent of what they wanted. They succeeded in their drive to consolidate about four dozen federal programs and shift the balance of power in education policy strongly back to the states. Many of the Democratic “wins” in the bill were about preventing even more conservative policies from becoming law, not advancing the vision of accountability-driven reform that Obama and his departing education secretary, Arne Duncan, promoted early in their tenure through competitive programs like Race to the Top. Duncan in particular has become a target of ire for conservatives, and Republican negotiators insisted on provisions that specifically rein in the secretary’s power to grant waivers in the manner that Duncan did.

“Never in my life have I seen major legislation driven as much by a desire to repudiate a Cabinet secretary and his way of doing business,” Hess said.

For years, Duncan has prodded Congress to fix the law, and he has repeatedly said that the waiver system was intended as a “stop-gap” to prevent schools from being hit with sanctions under No Child Left Behind. And while the administration is not happy with what it considers ideologically-motivated provisions that seek to curb the secretary's authority, Rodriguez said the White House was pleased that the new law would affirm the federal role in regulating education policy in many areas. He also said the agreement achieves key administration priorities by providing $250 million in annual funding for early childhood educations and by rejecting a House Republican proposal for “portability” in education dollars that Democrats worry would drain resources from schools in poor neighborhoods.

Passage of the new law could coincide neatly with Duncan’s departure as education secretary next month. But officials said the desire to finally get something done had more to do with the next president. Republicans want to do away with the waiver system, while even Democrats who backed Duncan are worried about what a GOP president could do with the authority the Obama administration has used. Privately, those who support accountability-based reform are also unsure of how a President Hillary Clinton would use the waivers, given her alliance with teachers unions and her recent endorsement by the National Education Association.

The agreement was reached just a few weeks after the Obama administration made a high-profile announcement that it would encourage schools to reduce the frequency of student tests, a move seen by critics as a mea culpa for a climate blamed in part on its policies. Advocates in both parties said they hope the new law will relax the test-prep classroom culture without abandoning accountability, but transferring power to the states offers few guarantees, and there are concerns about what the shift will mean for states that have had a persistently high achievement gap.

“What educators and parents are going to look for is, do we have some latitude to help our kids succeed? And do we have the tools and conditions that we need to help children succeed?” Weingarten said. “Or is it just going to be doubling down on federal policies, but on a state level?”

Related Video