Dealing with everything from “the Classification of Names of Dust and its Qualities” to “Poetic Descriptions of the Down on the Young Male Cheek”, via the ingredients of an omelette which increases sexual potency, a 14th-century Egyptian scholar’s attempt to catalogue all knowledge has been translated into English for the first time.

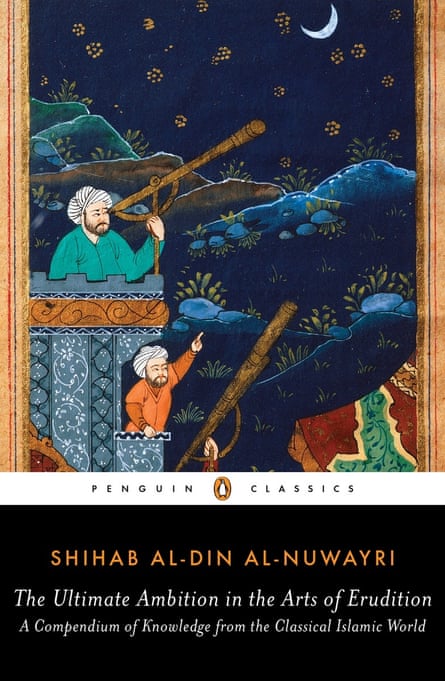

Shihab al-Din al-Nuwayri lived from 1279 and 1333. He was a civil servant in the Mamluk empire until he retired from government service in the 1310s and decided to catalogue everything known to exist, in an encyclopaedia which eventually spanned more than 9,000 pages and 33 volumes. Penguin Classics, which publishes the first ever English translation of The Ultimate Ambition in the Arts of Erudition in October, said that the compendium of knowledge from the classical Islamic world was “as important a work to civilization as Pliny’s natural history”, and “an astonishing record of the knowledge of a civilization”.

Ranging from history to poetry, and from biographies to natural history to medicine, The Ultimate Ambition contains everything from information on worshippers of the moon, to the names the Bedouin Arabs had for the sky, “including the Encrusted, because of its abundance of stars, and the Forehead, because of its smoothness”, to advice on how to escape from an angry rhinoceros. “A trustworthy person among the Abyssinians told me that rhinoceroses in Abyssinia charge at human beings to kill them whenever they spy them,” writes the author. “If a man climbs into a tree to escape, the rhinoceros will seek to smash it and kill him, but if the man urinates on the rhinoceros’s ear, it will run away and not return to him. That way, the man will escape from it. God knows best.”

His goal, al-Nuwayri writes in a preface, was “securing the essential and banishing the incidental, adorning it with the necklace of my own sayings, and the pearls of my predecessors”.

“My own words in it are like the night clouds leading the rain clouds, or the patrol followed by the squadron. They merely interpret the book’s contents and frame them like eyebrows over the eyes,” he writes, adding, warningly, “I have followed the traces of those excellent ones before me, pursuing their path and connecting my rope to theirs. So if there should be any complaint, the dishonour is upon them and not me.”

Nothing escapes al-Nuwayri’s all-encompassing eye. Considering dust, he writes that “Al naqʿ wa l ʿaqu¯b is the dust that swirls around the hooves of horses and camels. Al ʿaja¯j is dust stirred up by the wind. Al rahaj wa ’l qast˙ al is the dust of war; al khayd˙ aʿa, the dust of a battle. Al ʿithyar, the dust of feet.” He looks at the difficulties the female bear experiences in childbirth, and at eyebrows. “When the eyebrows are connected, this is called al qaran, which the Arabs despised [as they did] al zabab, which refers to hairy eyebrows, and al maʿat, which are patchy eyebrows.”

“Settling on what parts of The Ultimate Ambition to include and exclude was one of the great challenges,” said Brown University professor Elias Muhanna, who edited and translated the book. “The original work encompasses over 30 volumes, and I felt it was important to give the reader as broad a sampling of its contents as possible. That meant that I tried to include something – even just a snippet – from as many discrete chapters of the work as I could.”

But eventually, he said, he “still had to set aside a huge proportion of the text from al-Nuwayri’s history of the world”. He compromised by offering his readers “two bookends from that section: the story of Adam and Eve, which makes up the beginning of history, and some of the events of the author’s lifetime, which makes up the end of history.”

In his introduction to the book, which now spans just 352 pages, Muhanna writes that al-Nuwayri is “not so troubled by contradiction or ambiguity”, with “a chapter on the religious prohibition of sodomy and the punishment of the homosexual ... followed by a much longer chapter of poetry celebrating the charms of the male beloved”, and “a list of authoritative reports on the prohibition of singing ... followed by a catalogue of equally authoritative reports on the virtues of song, which introduces a 200- page stretch of biographies of famous singers in Islamic history”.

“Unfettered by the doctrinal shackles that moderns tend to associate with the medieval era, the world that The Ultimate Ambition presents is full of paradox and pleasure – which is to say, alive,” he writes.

Muhanna told the Guardian that in the past, people have “approached historical encyclopaedic texts in an instrumental way, reading them to answer questions rather than to appreciate them as literature”.

“If you think of an encyclopaedia primarily as a reference work containing objective information about the world, it is not apparent why you would want to read, let alone translate, a work that was woefully ‘outdated’. But if you think of an encyclopaedia as reflecting a vision of the world from a certain time and place, then there are many good reasons to read it,” he said.

“I hope that readers will recognize in al-Nuwayri’s work a sign of just how rich and colourful the intellectual heritage of Islamic civilization is. Perhaps more than any other literary genre, the medieval encyclopaedic compendium reflects the full range of a culture’s selves, not just its best self. It contains its official history, but also its browser history, if that makes any sense: the kitschy, crass, and embarrassing alongside the noble and self-important.”

The instructions for that potency-increasing omelette, meanwhile: “Take chickpeas, broad beans, eggs, and white onions, and cook them in milk until the moisture boils off. Then put it all into a mortar and pound it fine until it is all mixed together. Then add the yolks of ten eggs, put the whole mixture into a skillet, and fry it in oil.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion